Justin Baldwin hands me a business card. He is endearingly tense as he begrudgingly mingles at a benefit honoring his mentor Roger Shimomura—the infamous yet acclaimed artist known for his controversial social political art on Asian America. I immediately notice that Justin and I have two things in common.

(1) He is trying hard not to be uncomfortable at this elite social gathering.

(2) He is a Hapa.

Justin is seemingly a timid artistic type. Sporting black and grey-framed glasses, he totes around a digital camera that seems to serve as a security blanket. I observe him while I sneak bites of hors d’oeuvres under the table where I am to distribute gift bags to our swanky, exclusive guests of the Asian American Arts community. In an upper west side townhouse dominated by the wealthy, I truly feel like a gaijin in the country that I am halfway from. Perhaps this is a somewhat universal feeling.

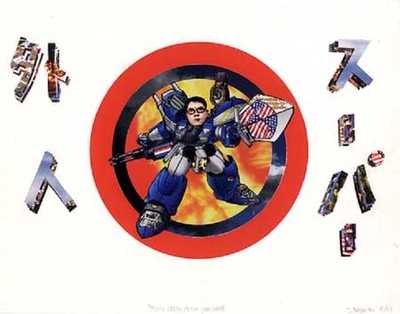

Printed on the back of Justin’s business card is an intricate yet cartoony self-portrait collage. In the portrait Justin is dressed in a stereotypically Japanese Power Ranger-like configuration. He carries an American flag shield inside of something that resembles a bull’s-eye with a heading that reads: Suupaa Gaijin.

I knew I had to interview him right away.

******

What is supposed to be a seventy-minute pseudo interview predictably turns into nearly six hours of deep conversation on art, identity and personal history. Although Justin is apologetic about the time consumption, I’ve recently grown accustomed to this type of meeting. Hapas tend to be ferociously eager and curious in the way neglected children can be when they find a trustful companion. Being cultural orphans, we all crave a sense of community—a place where we can feel like we belong. For us, such a place only exists in each other.

Justin and I café hop in the West Village and eventually settle into a slightly dingy, slightly fast food-ish Asian fusion restaurant.

“Do you want some gyoza?” I ask.

“Is it good?” he replies. And it’s not.

“I’m picky about gyoza,” he says, “because my mother makes it the best.”

Born in Kansas to a Japanese mother and a Caucasian father, Justin grew up amidst a big sky, beautiful fields and conservative people. Although his Sapporo native mother often told him stories about the country she left and since then missed, Justin’s tangible access to Japanese culture was somewhat limited. Like many otokonokos , Justin grew up enjoying robot toys, his mother’s kare-raisu (among other exquisite dishes) and shonen manga .

“The manga I was interested in wasn’t translated, so I couldn’t understand any of the text,” he says. “I used to trace the illustrations from Kozure Ookami comics to try to figure out how they were drawn. By reading these books, I learned a lot about visual communication and the power of images to tell stories.”

Justin’s interest in Japanese culture carried over to his studies at the University of Kansas where he majored in painting. Although he began to artistically explore the duality of his heritage as a student, it wasn’t until after graduation that he took a life-changing risk. In 1997 upon his acceptance into the JET program, Justin both mentally and artistically embraced a new found identity as the suupaa gaijin .

“I finished college and I didn’t know what to do,” he says, “I think a lot of people expected me to stay in academics. But a lot of my professors said that if you only stay in academics, then your art will always kind of be limited by that…it’ll be based on an artificial environment. And in order to really make profound art that transcends that, you have to also live outside of academics. So I decided to move.”

Venturing out to a foreign country after spending a sheltered adolescence in the Midwest is a typical desire for many young American college graduates. Young creative types especially tend to fetishize foreign places as a catalyst to gain a slapdash purpose and new perspective often “discovered” through an endless party with unfamiliar breeds of humanity. Justin’s quest was different. He courageously sought to rediscover his Asian roots after spending years viewing them as shameful—a common mentality held by many hapas who grew up in the states.

“Growing up in an environment that was mostly white,” he explains, “I can remember being kind of embarrassed of my Asian features or being ashamed of my different-ness and wishing I looked more Caucasian. Most of the icons that I was exposed to were White people and I didn’t even really realize how bad that was until much later in life. I felt so ashamed and I didn’t want to be half-Japanese. I wanted to be a white kid so that I could fit in with other white kids. It’s funny because Roger [Shimomura] told me he had a similar experience growing up in Seattle where there’s this huge Japanese American population. But the power of hegemony was so strong that he used to draw himself with blonde hair. And I think I actually did the same thing when I was really little.”

For the next three years, Justin worked as an English teacher in the Kagawa Prefecture through the JET program. At the end of his tenure, he signed on for an additional five years working directly for the Kurashiki Board of Education.

“I was living in the do-inaka where there were rice fields and mountains and the nearest super market was a thirty minute bike-ride,” he explains. “People would actually observe me using vending machines. I use to catch people staring in my window. Traffic use to literally stop when I walked along the street with drivers staring in slack-jawed amazement and shock at seeing a Gaijin! It was that intense. And none of these people could acknowledge my Japanese ethnicity. If I told them I was half-Japanese they thought I was lying or joking.”

Though he had toured Japan once prior to his move, the environment Justin catapulted himself into defied any preconceived notions he had harbored and molded based on his mother’s memories of life in the country where she grew up. This reverse cultural shock heavily influenced Justin’s work to the point of an artistic rebirth.

“Things had changed a lot since my mother first moved [from Japan] to the U.S.A. Daily life was different from movies and comic books, while most of the cultural studies I had undertaken as a University student were either very old, obscure, or both. After twenty-three years of being asked if I was Chinese, Japanese, Mexican or Native American by Caucasian Americans, I was surprised to find that most Japanese considered me to be the same as those Caucasian Americans. And even those who acknowledged my mixed ethnicity still considered me a Gaijin first and foremost. It was therefore only natural to explore this situation by making what I termed, Gaijin Art .”

The word “gaijin” is slang for the term “gaikokujin ” which is formed by combining the three kanji characters outside, country and person . As for me, this word brings back memories of adolescent life in Lexington, Kentucky. At the Japanese Saturday school I attended my classmates (who generally tended to be in the states because of wealthy Toyota executive fathers on temporary business) would still refer to local Americans as “gaijin ” or “foreigner”. I too, of course, was included in this grouping.

“By removing the character from country from the middle, ‘gaijin’ translates, literally, as outside person or outsider . I grew to dislike the term,” Justin says. “One reason is because when I traveled to Japan, I was designated an outsider even by my relatives, thereby severely limiting my access in many ways. To be fair though, part of what informs this is the fact that—although half Japanese American, I am not Japanese and never will be. From the Japanese point of view as a so-called ‘island nation’, which has a history of both geographic and political isolation, this designation also makes a certain sense.”

Instead of rejecting the notion of being an outsider in his (sort of) homeland of cultural heritage, Justin decided to move forward by embracing and exploring his creativity. During his time in Kagawa, Justin fervently constructed a series of multi-medium works that sought to transcend the boundaries of race. Justin bluntly titled the series GAIJIN Art , and made various exhibitions working eclectically with collage, photography, drawing, objects and some interactive projects. Though ambitious and critical, Justin’s body of work does not bombard the viewer with social elitism.

“Accessibility is important to me,” he says. “But I also try to provide enough for the more inquisitive to delve into the work further…more like a poem or paragraph. Ultimately, each person who views the work or participates in it completes it.”

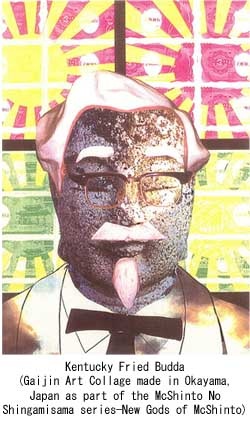

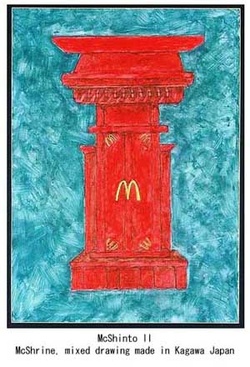

Fused with racially charged images and sly references to pop culture (check out his McShinto series) looking through Justin’s portfolio is like looking through an explosion of a cultural identity crisis. Although much of his art addresses issues relating to hapa identity such as the Gaijin Card (his reaction to the gaikokujin touroku shomeisho or Alien Registration Card) Justin’s work goes beyond self-examination.

“All the works that I made while living in Japan attempted to explore themes of identity, Japanese and American culture, history, cross-cultural communication, and internationalization, “ he says. “ I tried to ask questions and make observations in the form of visual riddles, puns, poems and jokes. I never expected the viewers or participants to understand my exact intent, hoping instead that I could provide enough accessible clues for them to personalize the works, finishing the art for themselves.”

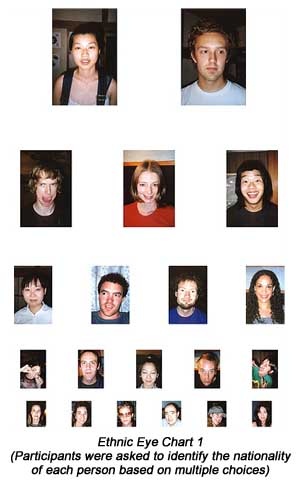

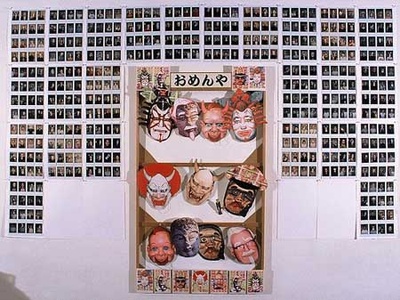

In Justin’s arguably most interactive project called Ethnic Eye Chart , participants were asked to identify the nationality of each person based on multiple choices. As a token of appreciation for each participant, Justin gave away (for free!) intricately constructed hand-made masks representative of various cultural icons (used in a partnered exhibit titled Omenya ). The result? A financial disaster but an artistic success.

“I find artistic elitism boring and counter-productive more often than not so,” he explains. “So it’s no coincidence that a lot of what I make is meant to be friendly and welcoming…even if there’s some critical content under the surface.”

By juxtaposing familiar content (like the golden arches of America’s favorite fast food joint) in unfamiliar ways (illustrating it on a stereotypically ‘Asian’ shrine and naming it McShinto), Justin hopes to create work that every viewer can connect with.

In every print Justin shows me, there are multiple layers. Behind every layer is a story. Behind every story is an artistic attack and execution. Justin possesses a rare and refreshing voice that takes on big issues while never losing sight of a reaction. More importantly, he is an artist who has unknowingly strengthened the voice of the biracial community not only in New York, but in the doinaka . By asking and introducing questions that are rarely addressed—his work is unique and meaningful, mysterious yet digestible. Humble as he is talented (perhaps because of his Japanese mother’s upbringing), Justin has no problem explaining himself or his work with the desire to learn and to teach others.

“I realize now, looking back at the Gaijin Art , that it was all part of a quest of sorts, trying to find a cultural home. The Gaijin Art may be finished, but the journey continues.”

To learn more about Justin Baldwin’s art, go to www.justinbaldwin.net or email justin@justinbaldwin.net.

© 2009 Leah Nanako Winkler