On February 19, 1942, less than 74 days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which set in motion the subsequent exclusion and detention of all Americans of Japanese ancestry, whether aliens ineligible for US citizenship (Issei) or their U.S.-born citizen children (Nisei) and grandchildren (Sansei), living on the West Coast. The military began rounding up Japanese Americans as early as February 27, giving some as little as 48 hours to pack up. Within four months, more than 110,000 people had been removed from their homes and transplanted to makeshift detention areas—called assembly centers—newly transformed from race tracks, fairgrounds, labor camps, and the like. Only the dying or desperately ill were left behind in hospitals or sanitariums, separated from the support of their families. It has become apparent that the speed with which people were ousted from their homes and transferred to barbed wire enclosures was the cause of many subsequent health care problems.

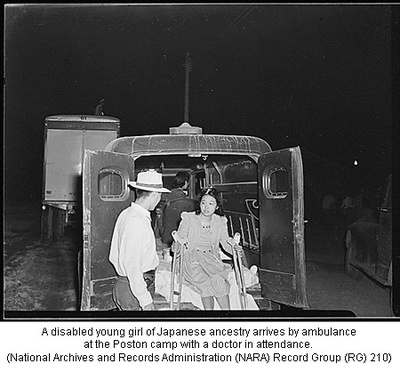

With the logistics expertise that perhaps only the U.S. Army was capable of mobilizing, virtually no one was left behind—not Mitsuye Endo, a Nisei woman who challenged the legality of the incarceration, not some 90 young orphans, nor the disabled. Clearly, the government considered all Japanese Americans imminent threats to the security of the United States. If you could walk, even with crutches, you were imprisoned.

Constitutionally, there was no precedent for the blanket incarceration of American citizens and legal resident aliens, and operationally, there was no precedent for an incarceration on such a massive scale. It had never been done before, so there were no blueprints to follow (though sadly that is no longer the case). How was it possible to imprison men, women, children, the old, and the sick, in such a short period of time? The actual rounding up of individuals was done like clockwork, although the subsequent imprisonment was a different story. Many of my interviewees recounting their departure have expressed opinions that the government knew exactly where they were. Indeed it was revealed just recently that the US Census Bureau assisted in tracking everyone down, contrary to its charter of strict protection of individual privacy.

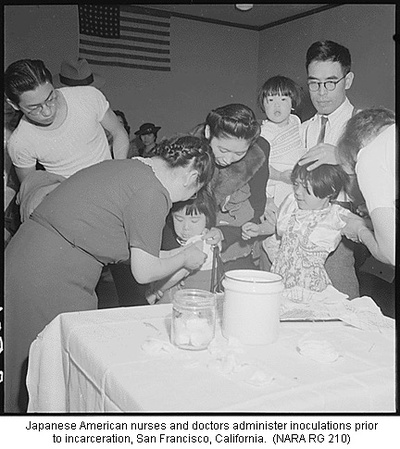

The precipitous rush to incarceration and the crowded conditions put people at risk for communicable diseases, and they needed to be protected. The possibility of contagious infection was recognized by Japanese American physicians prior to entry in the temporary detention centers, and they tried valiantly to vaccinate people against typhoid and smallpox before they left their home communities. They could reach only a small percentage, and the task of inoculating the remaining thousands continued upon entry into the temporary detention centers and again at the permanent detention or “relocation” centers.

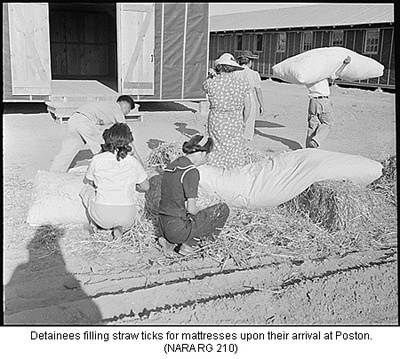

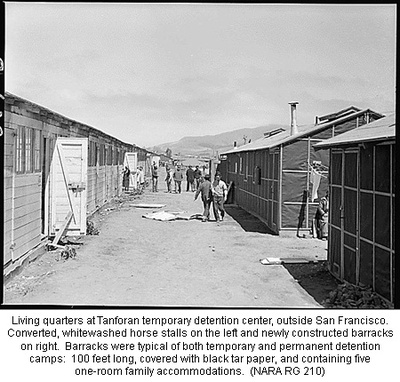

The army built the detention facilities based on a master plan designed for young healthy male recruits, complete with mess halls, communal bathrooms, and rough-hewn barracks. It did not take into account the needs of women, children, and the elderly. Initially, thousands of people were sent to the local temporary detention quarters. The first arrivals entered horse stalls still redolent of manure or hastily built barracks, occupying single rooms that housed entire families or unrelated couples or individuals. Bedding most often consisted of cots and self-filled straw mattresses. There was no interior plumbing. In the permanent centers, heat was provided by wood- or coal-burning stoves. All labor needed within the interior of the confines of detention was done by the internees themselves; overnight people became cooks or bottle washers or whatever was needed—whether they had any prior experience or not. This inexperience led to multiple episodes of food poisoning in all of the centers. The army had not thought to include training people in the necessary procedures for large-scale food handling, storage, and refrigeration.

Medical facilities were haphazard from place to place. In the Portland Assembly Center, in Oregon, army barracks served as hospital ward and clinic for nearly 4,000 people. Unprepared to oversee medical facilities, the army enlisted the U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) to administer the centers and see to the care of the detained. Immediately, a lack of health care personnel was apparent. The USPHS called upon imprisoned health-care professionals to run their own detention medical facilities. The Issei and Nisei health-care professionals stepped up to the plate to create a health-care system where none existed. While USPHS professionals had made plans, it was the internees who implemented them and dealt with the problems caused by a lack of supplies, equipment, and staff. The staff shortage never abated. And as time went on through resettlement or the military draft, the professional medical staff decreased, often drastically. Supplies, equipment, and medicines were assuredly ordered, but they did not always arrive.

Emergency cases were sent to local hospitals when possible. One of the first health-care casualties was pregnant women. In the first days at the Tanforan Assembly Center, near San Francisco, California, Tomoye Takahashi described how Dr. Kazue Togasaki, faced with a pregnant woman in labor, ordered onlookers to tear a door off a laundry room that she then used as a delivery table. The army had not thought about female health-care needs. This was not an isolated case. In Marysville Assembly Center, outside of Yuba City, California, Dr. Shigeru Hara arrived to find no delivery table at his center, and asked his brother to make one out of scrap lumber. Fortunately he thought to bring this table to the Tule Lake Relocation Center, located on the California-Oregon border, where it was desperately needed.

In the confusion of thousands of people arriving at the temporary assembly centers, the initial days were chaotic. Eventually through their ingenuity and resourcefulness, the detainee medical staff was able to fashion a workable system. But by the end of the summer of 1942, everyone was uprooted once again and transported via buses and trains—shades drawn—to 10 permanent camps in remote and unfamiliar regions. Again upon arrival they were greeted with unfinished medical facilities, a lack of equipment, medicines, and supplies, and a dearth of health-care personnel. The War Relocation Authority (WRA), a civilian bureaucracy newly created to run the camps, was loath to allow doctors of Japanese heritage to continue in charge of the medical care, and so they put them under the supervision of a Caucasian chief medical officer and the nurses under a Caucasian head nurse. It was a move that created tension and resentment and underscored the inherent racism pervasive throughout the mass incarceration.

Dysentery

The permanent detention centers had many public health problems; some were corrected within months, while others lasted the duration of the war. At first, most of the camps had unsanitary and unpalatable supplies of water; moreover, conditions of water contamination lasted more than a year in several locations. With metal at a premium during the war years, the WRA used recycled oil pipes that reeked of hydrocarbons and had an oily residue to transport the water. A report from Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming described the conditions the hospital faced: “The water was terrible because of the rusted and oiled pipes, and it really was not fit to use. The water was hauled. There were two or three barrels in which the drinking water was kept. As for bath water, we would run the faucets all night and clean out the pipes.” Dr. Yoshiye Togasaki, a public health specialist imprisoned at Manzanar, immediately recognized the problem using untreated surface water from the Sierra Nevadas of eastern California. Through her prodding, a filtration and chlorination system was installed, and the water was thereby made safe for human consumption.

While the vaccination program helped contain the spread of contagious diseases, the problems with unsafe food preparation, storage, and handling continued to bedevil the internees in the permanent camps. Dysentery was so common at Jerome Relocation Center, one of the Arkansas camps, it was called “Jerome Disease.” As late as 1944, Poston Relocation Center in Arizona continued to have problems with contaminated milk supplies, and the Sanitary Engineer at the Gila River Relocation Center, Arizona’s other WRA center (which, like Poston, was located on an Indian reservation) reported that they had “the unsafest of all War Relocation Authority fresh milk sources,” a situation that lasted throughout the life of the center. In late 1943 Jerome and Rohwer Relocation Center (the other Arkansas camp) were plagued with E. coli contaminated water and milk supplies. On the other hand the Heart Mountain camp had one of the best, for the nearby Cody (Wyoming) Dairy consistently delivered safe milk supplies.

Dust

Environmental health hazards were one of the most enduring problems of the permanent camps. Located in regions of desert, arid high plains, or swampland, each camp was presented with unique difficulties, yet dust was a source of health problems and the most common source of complaints from internees. In preparation for the camps, the army had stripped the entire 640-acre camp sites of all native vegetation, thus creating a miasma of dust pollution. People complained of waking to see crime scene-like outlines of their bodies on the bedding from the dust that blew through the walls of the poorly constructed barracks. The prevalence of the dust increased the incidence of asthma at the centers. As late as August 1944, the chief medical officer at the Amache Relocation Center in Colorado reported many transfers of asthmatics because the climate in southwestern Colorado was thought to be beneficial for people with lung problems. Amache itself experienced major dust storms three to four times a month, eight months out of the year. The Tule Lake center was built on a dry lake bed and had its share of dust problems. Tule Lake surgeon, Dr. George Hashiba complained of the difficulties maintaining a sterile environment in the operating room where dust filtered in and urged sealing the windows.

No camp suffered more from dust problems than Gila River in southeast Arizona. Coccidioidomycosis or Valley Fever was endemic in the area and ubiquitous in the dust at the newly cleared campsites of Rivers and Butte, which together comprised the Gila River Relocation Center. There are many manifestations of coccidioidomycosis: a skin condition, cocci meningitis, cocci arthritis, cocci pneumonia, and cocci influenza. The acute variety was usually self-limiting, but a progressive type was often fatal. For some people who were infected, it became a lifelong disability. The dust storms at Manzanar located in eastern California’s Owens Valley proved debilitating. Dust off the dry lake beds is saturated with toxic heavy minerals. Recent studies by the Environmental Protective Agency note that the small size of particles in the dust (less than 10 microns) penetrate more deeply into the lungs causing a variety of respiratory problems and autoimmune disease. Children, the elderly, and people with lung problems were especially at risk. The dust permeated everywhere and everything. The Arkansas camps built on swamplands presented their own difficulties. Efforts were made to drain the swamps and control the mosquito population as people were at risk for malaria. These efforts were successful as malaria did not get a hold in the camps.

The most serious health issues involved the care of newborns, young children, and older people. Dietary deficiencies and a lack of medicines caused problems for diabetics and growing young children. It was especially tough in the hot summer heat of camps located in the southern tier of the country where temperatures in the hospitals were reported to reach over 110 degrees. There were reports of children dying from dehydration. One mother I interviewed saw women on either side of her lose their babies to the heat in Poston and felt survivor guilt that her little girl was spared. Another interviewee described how his young son lost his hearing in one ear due to a heat-induced fever and dehydration. These cases of dehydration could have been prevented by the installation of cooling equipment available at the time and requested repeatedly by the chief medical officers. In the face of deficiencies in planning, medicines, supplies, and equipment, the medical staff persevered to give the best care they could.

For some people, the health care offered to them as incarcerated people was the most they had ever seen. Prior to World War II, there was no safety net for the impoverished and communication in English with the predominantly Japanese-speaking Issei sometimes impeded treatment. But in the camps, all but the overseeing physicians were internees like themselves, many fluent in Japanese, with readily available translators. A number of people were able to get their teeth fixed, glasses, and long- term chronic conditions, such as hernias, addressed. Many Issei bachelor farm laborers entered the camps with trusses to hold their hernias in and were able to see this condition corrected after the initial phase of triaged health care. Even so, WRA officials censored detainee physicians for performing “elective” surgeries. The official mandate was “the provision of the minimum essential of living, viz., shelter, hospital, etc.” With that statement, the government declined a request for additional hospital beds and out-patient facilities to treat people with tuberculosis. Many TB cases were considered a chronic not acute illness and therefore out of the purview of the WRA. Detainee physicians overcame this obstacle by training family members to care for ambulatory patients.

By February 1943, the army started drafting young men from the camps. A number of the physicians signed up, such as Dr. Robert S. Kinoshita of Heart Mountain, who first volunteered before the war but was sent instead to Portland Assembly Center. The exodus into the armed services depleted the number of physicians and health-care workers in all the camps. At the same time, once a controversial loyalty oath was signed, people were allowed to leave the camps for places inland if they had work or a school willing to accept them. Denver, Colorado, and Chicago, Illinois, were common resettlement destinations: the Japanese American population of Denver, for example, more than quadrupled during the war years, while Chicago’s enlarged by nearly 25,000 before the end of the war. As physicians departed, situations became so desperate that the WRA prevailed upon Jewish refugees to go to Utah to practice at the Topaz Relocation Center. And while their presence was welcome, their lack and the Issei’s lack of English language skills complicated patient/doctor communication. By the middle of 1944 with war coming to a close, human resources were so diminished there were only four doctors in Poston, the largest detention center, with roughly 20,000 inmates, including one lone obstetrician to deliver Mabel Ota’s baby. When she went into labor, the doctor was too exhausted from previous deliveries and his having to rest prolonged her labor by more than 24 hours. Finding she needed a C-section and no anesthesiologist available, the doctor struggled to deliver the baby with forceps which caused irrevocable brain damage to this otherwise healthy baby girl.

Determination

There is ample evidence that the WRA mismanaged and poorly administered the health-care delivery system in the detention centers. A constant litany of lack of supplies, equipment, and personnel hampered the optimum delivery of health care—a litany that persisted throughout the existence of the camps. Potential public health disasters were averted only through the determination and dedication of the detainee health-care professionals themselves. When faced with shortages, they improvised. They toiled long hours to compensate for the lack of medical staff. They stood up to the deficiencies and racism in the WRA system and demanded care and services for their patients. Without these determined men and women, the welfare of more than 110,000 people would have been severely at risk. Overall, the determination to survive and prevail over the trial of incarceration characterized all of the internees. And it was their strength and determination that they drew upon after the war to resettle and reestablish their lives so abruptly altered in 1942.

* Gwenn Jensen is one of the panelists in a presentation titled "From Camp to Community: Japanese American Health Care" at the Enduring Communities National Conference on July 3-6, 2008 in Denver, CO. Enduring Communities is a project of the Japanese American National Museum.

© 2008 Gwenn M. Jensen