Today’s Arizona has hosted multiple civilizations for thousands of years. During the first millennium A.D., the Huhugam established villages in Arizona’s Lower Gila Valley and the Sonoran Desert of northern Mexico. Distinct indigenous cultures, including the Maricopa, Navajo, Apache, Walipai, Yavapai, Aravaipai, Pima, Pinal, Chiricahua, Cocopah, Hopi, Havasupai, Pascua Yaqui, Kaibab-Paiute, and Quechan coexisted throughout the area. But with sixteenth-century Spanish colonization and eventual settlements here, tensions flared between colonists and Indian nations.

The region underwent more dramatic change in the aftermath of the 1821 Mexican Revolution in which Mexico overthrew Spanish rule. Manifest Destiny motivated the arrival of land-seeking American families and individuals. The U.S.-Mexico War in 1848 and the subsequent 1853 Gadsden Purchase resulted in the U.S. adding Arizona territory (and other lands) from Mexico. Establishment of territorial status in 1864 further diversified Arizona. Completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1877 contributed to the opening of mines and the development of agriculture, which attracted more migrants from throughout the U.S. and increased the U.S. Army presence to protect these Euroamerican settlers. In 1912 Arizona became the forty-eighth state.

For American Indian communities in this territory, the ongoing arrival of foreigners caused great turmoil, violence, and dispossession. From the 1850s to the turn of the twentieth century, conflict between new migrants and indigenous communities led to the latter’s relocation to reservations. Two distinct communities, the Pima in the Gila Basin and the Maricopa from the Southern Colorado River, coalesced by executive order into the Gila River Reservation. The Mohave and Chemehuevi, living in western Arizona along the Colorado River, were moved in 1865 to a US government-established reservation for Colorado River Indian tribes.

Increased population magnified Arizona’s diversity. California’s anti-Asian sentiment and violence contributed to Chinese and Japanese Americans moving to the Southwest. African Americans settled initially as farmers, cowboys, and freighters in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; cotton production attracted more migrants from the Cotton Belt. The swelling Japanese American, or Nikkei, population at the twentieth century’s dawning was due mainly to agricultural expansion in the Salt River Valley, which also experienced the concurrent migration of Mexicans from southern Arizona and Mexico’s Sonoran region.

Settlement patterns, class distinctions, and institutional racism sparked interactions of Nikkei with African Americans, Mexican Americans, and American Indians. In the 1920s and 1930s shared socioeconomic status and occupation shaped the co-ethnic neighborhoods of South Phoenix with African Americans, Yaqui Indians, and Mexican Americans who worked close by Chinese entrepreneurs and Japanese agriculturalists. In Tucson, Mexicans and Yaqui Indians settled barrio libre, which included Chinese capitalists and Anglo merchants and farmers.

Arizona was not a primary destination for most mainland Japanese immigrants, or Issei, who moved east of California for land, jobs, and opportunities. Some came north to Arizona from Mexico. Labor demand for Japanese male workers resulted from the exclusion of Chinese immigrants in 1882, when the Southwest’s need for mine and railroad workers peaked and agriculture emerged as a key industry. In Phoenix, many Issei were agricultural workers; in Williams, they were chiefly railroad workers.

By the turn of the century, more Japanese American families settled in the Salt River Valley, where they often leased land and planted corps. Because they trucked their crops to the downtown Phoenix market, such small-scale agriculture was termed “truck farming.” Wives and daughters worked on the farm with men: supervising the workers, sorting and washing produce, and packing crates for market in addition to domestic duties. They also sold produce from stands on their farms. Glendale then had the largest Nikkei community, with another community in South Phoenix by South Mountain and a smaller one in Mesa.

These families stimulated the growth of the valley’s Japanese American community, which led to a demand for rice and shoyu (soy sauce). A few Phoenix and Glendale businesses imported Los Angeles goods for sale to the local population. Only a few Japanese farmers and merchants existed in Phoenix proper, but most farmers drove their produce to the Phoenix market in the early morning to sell to grocers, while most families drove into the city for shopping. After the 1930s US boycott of Japanese goods, the Tadano family in Glendale opened the nation’s first shoyu factory.

Community members also created cultural institutions. H. O. Yamamoto and his wife founded the Buddhist Church. In 1932 Reverend Seki held the first services in an empty building on their land, and four years later the church opened a building at 43rd Avenue and Indian School Road. Some members of the U.S.-born citizen generation, or Nisei, recall their parents carving the original pews and altar from wood. A Christian convert, Kiichi Sagawa, held Sunday School on his property in Tolleson, and eventually he purchased land for the Japanese Free Methodist Church founded in Phoenix in 1932.

Transcending differences of faith, the community as a whole supported the Japanese language schools in Phoenix and Mesa. The Issei wanted their children to acquire the Japanese language and understand Japanese culture. Nisei recall lining up to enter school, learning Japanese history, and celebrating the Emperor’s birthday on the school grounds. Additionally, boys could attend martial arts classes in both Mesa and Phoenix, and after World War II, girls could learn traditional dance when Janet Ikeda, trained in Japanese dance, moved from Los Angeles to Mesa.

Along with other minority groups, Nikkei suffered institutional racism. State and federal legislation discriminated in the areas of immigration, citizenship, land ownership, and marriage. Asian-descent immigrants could not become naturalized. Since the livelihood of most Arizona Nikkei revolved around agriculture, laws regulating land ownership of non-citizens significantly affected their opportunity to make a living. Alien land laws in the US West commenced with California’s 1913 and 1920 statutes. Following suit in 1921, the Arizona legislature restricted land ownership to citizens, effectively prohibiting Issei from purchasing land. But Japanese farmers subverted these restrictions by leasing land from Euroamericans or purchasing it in their citizen children’s names.

In 1865, Arizona’s territorial legislation passed its first law regulating inter-ethnic marriage by prohibiting “Caucasians” from marrying blacks and mulattoes. Subsequently the Arizona Supreme Count ruled that people of mixed Caucasian ancestry could neither legally marry in Arizona nor, because they were not considered Caucasian, challenge the statute’s constitutionality. This restriction extended to “Orientals,” thus further restricting marriage partners for Japanese.

Educational segregation was a primary area where racially biased legislation impacted Arizona’s minority groups. In 1909, the territorial legislature endorsed the segregation of black students. The 1912 constitution mandated African American segregation at the elementary level and permitted it in high schools. Though not mandated by statute, other ethnic minorities, statewide, were placed in segregated schools. Romo v. Laird in 1925 successfully challenged school segregation, allowing Mexican Americans to attend the white-only Tenth School in Tempe. Nonetheless, segregation continued statewide. American Indian students were consigned to segregated boarding and reservation schools from 1925 to 1950.

Withholding suffrage also suppressed the rights of ethnic minorities. Not until 1924 did the federal government recognize American Indians as US citizens. Only in 1948 were American Indians allowed voting rights. The Arizona legislature passed other statutes intended to restrict voting rights for minorities. A 1912 literacy test required all voters to read English, which significantly affected Arizona’s Spanish-speaking citizens. The Federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 subsequently outlawed literacy tests.

The pervasive institutional racism in Arizona during the first half of the twentieth century was reflected on the urban landscape. In Phoenix African Americans were concentrated in select areas by neighborhood covenants prohibiting home sales to black buyers, while mortgage companies exacerbated the division by advancing credit only to families settling in specified neighborhoods. This type of de facto segregation extended to Mexican Americans. Early Anglo settlers relegated Mexican residents to the most marginal land. Over time these communities became barrios with racially segregated schools and public facilities. Swimming pools, movie theaters, and drug stores excluded or separated blacks, Mexicans, Japanese, Chinese and any others that city leaders and business owners deemed inferior.

World War II, especially the US government’s detention of Nikkei, profoundly affected Japanese Arizona. Whereas Japanese global power during the 1920s and 1930s had protected Japanese Americans, Japan’s December 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor not only precipitated war with the US, but also had negative ramifications for the Nikkei (the majority who considered themselves “American,” not “Japanese”). In February 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of “designated persons” from military zones in the western states.

One such zone literally split the state of Arizona and its Japanese American community in two. A mere street determined that some families would be “evacuated” into concentration camps, while others remained “free” outside the camps. Those removed were placed in Poston, the only “relocation center” administered by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, on the Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT) reservation. Just as California, Washington, and Oregon had “assembly centers” to hold people before the War Relocation Authority-managed camps were constructed, Mayer Assembly Center, a former Civilian Conservation Camp (which was open merely a month in 1942), held southern Arizona evacuees until their transfer to Poston. Poston had three separate communities: Poston I, II, and III. Arizona’s second WRA center, Rivers, was also on Indian land, the Gila River reservation, and consisted of the Butte and Canal camps. In addition to being the sole state where the WRA sited its relocation camps on Indian land, the town of Leupp on Navajo land also hosted an isolation center for “citizen troublemakers” at a onetime Indian boarding school in 1943. Catalina Federal Honor Camp in Southern Arizona was a federal prison that held less than fifty draft resisters from the Poston, Granada (Colorado), and Topaz (Utah) WRA centers, including constitutional resister Gordon Hirabayashi.

Together the Rivers and Poston camps held over 30,000 Nikkei, nearly one hundred times the size of the 1940 Japanese American community, and far outnumbering the residents of the reservations housing them. Both camps provided opportunities to reclaim desert areas for agricultural cultivation. Poston internees helped complete the Parker Dam to supply irrigation for agricultural development. Local farmers hired Gila River internees to pick cotton and do other field work, while other camp denizens manufactured camouflage nets and other war-related items. Poston and Rivers also saw many of their sons enter World War II in the armed forces or military intelligence service.

Those Nikkei families in Glendale and Mesa living north and east of the “dividing line” remained free from detention, but not the racist hostility directed at their ethnic community. Grocery and department stores would not serve them, and Japanese Americans could only enter Phoenix with a permit or if accompanied by a Euroamerican. Some families thus experienced great hardships, surviving on what they farmed, and relying upon hired workers to represent them honestly when selling their produce at the Phoenix market. Some of these families who were not evacuated yet adversely affected by internment successfully claimed reparations in the 1990s from the US government.

Equally significant was the Arizona community’s role in assisting Japanese Americans relocated to their state from California. When released from confinement, they lived on the farms or in the homes of Japanese Arizonans, worked for them, and received temporary assistance from them to rebuild their lives. While most Japanese American relocatees returned to California within a year or two, others remained as members of post-World War II Arizona’s Japanese American community. In the 1950s, the Gila River leadership agreed to not disturb the camp sites so long as they did not need to use the land. They have honored this verbal commitment to the present day.

The politicization of Japanese Americans in the postwar era echoed the growing politicization of ethnic minorities in Arizona and nationwide. Wing F. Ong became the first Asian American to be elected to a state office in 1946. Desegregation of high schools in Arizona began in 1949-1950. In 1951, the Arizona legislature amended the law mandating the segregation of African American students, leaving it to individual districts to desegregate as desired. In 1953, the Superior Court ruled school segregation unconstitutional. This ruling was followed on May 5, 1954, by a similar judgment just twelve days before the US Supreme Court handed down its Brown v. Board of Education verdict.

The Walter-McCarren act reversed the exclusion of Japanese-born individuals from US citizenship in 1952. This act specifically deleted racial exclusions and established quotas based on national origin. All immigrants from Asia could now become citizens on an annual quota basis. Japanese Arizonans actively lobbied their state senators and representatives to support this bill. After the law passed, the Japanese American Citizens League held citizenship classes in English and Japanese. Although not all Issei elected to be naturalized and not all Nikkei opted for JACL membership, the fact that Issei had a choice to become citizens was a significant milestone for Japanese Americans. A Japanese American also was directly involved in overturning the Arizona statute that denied interracial marriage. In 1959 Judge Herbert F. Krucker overturned Arizona’s anti-miscegenation law when he forced the Pima County clerk to recognize the marriage of Henry Oyama, a Japanese American, and Mary Ann Jordan, a Euroamerican, as well as the marriages of four other interracial couples.

Civil rights struggles continued well into the 1960s, reflecting the influence of national social movements for equality. Beginning in the late 1950s, a bill prohibiting racial discrimination in public places (public accommodations) was defeated several times in the legislature. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Youth Council responded with organized sit-ins starting in 1960. In 1963 over a thousand protestors marched on Phoenix City Hall to attain commitment to equal employment. After increased protests, a public accommodation bill was passed in 1964. Attempts to establish a Martin Luther King Jr. state holiday began in 1972; in 1990, voters rejected the holiday, resulting in the state losing the fight to host the Super Bowl. In 1992, Arizona became the forty-ninth state to observe the holiday, and the only one to do so with voter approval.

Mexican Americans likewise protested discrimination. The non-profit Chicanos por La Causa was founded in 1969 to advocate for equal rights. High school students boycotted Phoenix High School the following year because of discriminatory practices and high drop-out rates. In 1974, Raul H. Castro became Arizona’s first Hispanic governor. Yet the struggle against discrimination has continued even into the present with heated debates over immigration and immigrant rights that focus primarily on Mexican migrants.

American Indian communities in Arizona face continued challenges to their sovereignty in terms of resource management and economic development. In 2006, the Navajo and Hopi nations settled a forty-year dispute over land that had resulted from partitioning by the federal government. The success of some Indian communities in gaming has resulted in repeated political initiatives to decrease tribal sovereignty by increasing taxes and regulation of Indian gaming in Arizona. Water rights continue to be contested. Some Navajo are seeking to stop Peabody Coal Company’s drainage of an aquifer beneath Black Mesa, and in 2005 Gila River won a water rights settlement (the largest such claim in the western US). In March 2007 a federal appeals court upheld an injunction sought by several nations against The Arizona Snowbowl ski resort’s use of recycled waste water to produce snow on the grounds that this violated sacred land.

With Southeast Asian refugees arriving in the 1980s, and rising numbers of highly-skilled Filipinos, South Asians, and Chinese immigrant workers recruited for the state’s developing knowledge economy and health-care industry in the 1990s, Arizona’s Asian American community has increasingly diversified. Since the 1960s, Arizona has also attracted migrants from the Pacific Islands-Guam, Hawai’i, Tonga, Samoa, and the Micronesian Islands-and in 2000 boasted the ninth highest Pacific Islander population among US states. The Japanese American community has also changed. Reflecting national trends, Japanese Americans were the only Arizona Asian American subpopulation to decrease in 2005, possibly due to outmarriage and declining Japanese immigration. Due to global competition, their children’s different career paths, and the premium on land in Maricopa Valley, most Japanese Americans by 2007 had sold their farmland to developers.

Nonetheless the Japanese American community, particularly those involved with the JACL Arizona Chapter, the two primarily Nikkei congregations in Phoenix, the Tucson Japan America Society, and other civic and business organizations, maintain a cultural and community presence. The JACL and Arizona State’s Asian Pacific American Studies Program began the Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project in 2003 to document the community’s history. In 2006, the JACL Arizona chapter hosted the National JACL Convention at Gila River, and dedicated a memorial to the internees at the Gila River Arts and Crafts Center, where the chapter also maintains a small display about internment and Nisei soldiers. A memorial will be erected by the former Kishiyama farm to honor the Japanese American flower growers along Baseline Avenue in Phoenix, whose fields of flowers attracted tourists and dignitaries from the late 1950s to 1980s.

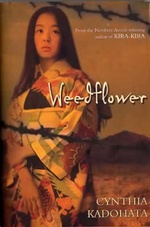

Collaborations statewide continue to sustain Arizona’s collective memory of internment. The Arizona Humanities Council sponsored the 1997 Transforming Barbed Wire conference about the shared Japanese American and American Indian experiences at Gila River during World War II. Lane Nishikawa’s play about internment, “Gila River,” was first performed in 2000 by local Japanese Americans at the Arts and Crafts Center. In 1999 the Colorado River Indian Tribe designated 40 acres for a Poston educational site. CRIT members began collaborating with former internees in 2001 on the Poston Restoration Project to rebuild Poston I and open a museum. The Poston Memorial Committee built a memorial at the former site in 2002. OneBook Arizona—a statewide reading program—selected Cynthia Kadohata’s novel Weedflower, about an interracial friendship at Poston, for its 2007 children’s selection.

The state increasingly recognizes individual Japanese American contributions as well. In 2003, the Tucson Unified School District dedicated the Henry “Hank” Oyama Elementary School in honor of his educational leadership and work in Mexican-American bilingual education. Due to Chandler resident Bill Staples’ efforts, Arizona Governor Janet Napolitano declared November 10, 2005, “Kenichi Zenimura Day” after the legendary Japanese American baseball player who, as a Gila River internee, constructed a field and organized a camp baseball league and, in 1945, coached the Gila River Eagles to victory over Arizona’s top high school team, the Tucson Badgers, at Butte Camp. In 2006, surviving members of both teams reunited and recalled how Kenichi Zenimura and the Badger’s coach, Hank Slagle, transcended racial differences and defied popular opinion.

Arizona has experienced rapid population growth in the past few decades, and this population growth results in increased diversity. Recently, for example, the state has welcomed refugees from Burma and Sudan. The state’s challenge is how it will respond to the challenges of diversity and growth-spiraling demand for resources and the need to ensure equal access to services and opportunities-while encouraging and sustaining the democratic engagement of all of its residents.

* * * * *

Timeline for Japanese Americans in Arizona

(Compiled by Karen J. Leong)

1865 Arizona Territorial Legislature passes law prohibiting Euroamericans (e.g., “Caucasians”) from marrying blacks or mulattoes.

1870 US Census begins to count persons of Japanese descent.

1877 Anti-miscegenation law revised to forbid intermarriage between Euroamericans and American Indians.

1882 First Chinese Exclusion law passed, forbidding entry of Chinese laborers. (extended indefinitely in 1904, and repealed in 1943) and resulting in recruitment of Japanese labor to the United States and Hawai’i.

1885 Japanese immigrant Hachiro Onuki comes to Arizona, and changes name to Hutcheon Ohnick. Ohnick becomes a naturalized US citizen and partner in the first electricity and gas plant in Phoenix. He and Catherine Shannon wed in 1888.

1897 Japanese agricultural workers hired in central Arizona territory.

1900 US Census counts 281 Japanese in Arizona Territory.

1905 120 Japanese laborers brought to Salt River Valley to work on sugar beet farm.

1906 First Japanese permanently settles in Maricopa County.

1907 President Theodore Roosevelt brokers Gentlemen’s Agreement with prime minister of Japan to halt migration of Japanese workers to the United States. Japanese migration for family reunification still permitted.

1909 Japanese workers for hire advertised in Prescott newspaper. Increasing numbers of Japanese truck farmers thrive in central Arizona, growing cantaloupe, sugar beets, lettuce, and strawberries.

1910 US Census counts 371 Japanese in Arizona Territory. Arizona Japanese Association founded. Free Methodist Church and People’s Mission in Mesa work with Japanese in Salt River Valley.

1912 New Mexico and Arizona gain statehood.

1913 Arizona passes first alien land law, following California’s lead

1917 Editorial in Mesa Daily Tribune praises patriotism of Japanese in Red Cross activities supporting local troops.

1920 US Census counts 550 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1921 Arizona passes a stricter alien land law.

1929 Mr. and Mrs. Kiichi Sagawa initiate first Japanese Protestant Christian meetings.

1930 US Census counts 879 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1932 Japanese Free Methodist Church dedicated.

1933 Reverend Hozen Seki arrives to lead Buddhist Church at H.O. Yamamoto farm.

1934 Euroamerican farmers, discontented with poor economy, begin an anti-alien movement intended to force all Asians out of Arizona. Ten Japanese farmers are assaulted.

1935 Japanese Consul’s intervention with federal government halts violence, but acreage farmed by Japanese drops from 8000 acres to 3000.

1936 The Arizona Buddhist Church building in Phoenix opens (in the late 1990s, the church changes its name to Arizona Buddhist Temple).

1940 US Census counts 632 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1941 The day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, FBI agents visit several Japanese American families in Arizona, taking away heads of households and community leaders. Members of Japanese Buddhist Church and Japanese Americans in general destroy Japanese items.

1942 General John De Witt sets up military zones down the West Coast. The dividing line demarcates the southern third of Arizona as restricted, and also splits Maricopa County in half between restricted and free zones. Mayer Assembly Center opens for one month. Internment camps constructed at Gila River Reservation and Colorado River Indian Tribes Reservation.

1945 Rivers and Canal camps at Gila River closed. Poston I, II, and III camps in Parker closed.

1950 US Census counts 780 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1952 Congress passes the Walter-McCarren Act, which revises US immigration law and renders Japanese-born immigrants right to naturalized citizenship.

1956 Over forty Arizona Issei become naturalized citizens.

1957 Original Buddhist Church burned down due to arson.

1959 Hank Oyama and his bride Mary Ann Jordan, along with four other couples, successfully challenge Arizona’s anti-miscegenation law.

1960 US Census counts 1,501 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1961 New Buddhist Church building dedicated.

1970 US Census counts 2,394 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1976 City of Phoenix becomes a sister city with Himeji city in Japan.

1980 US Census counts 4,074 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1984 The City of Phoenix (along with the Japan-America Society of Phoenix, the Japanese American Citizens League Arizona chapter, Himeji Sister Cities Committee, Arizona Buddhist Church, and Phoenix Japanese Free Methodist Church) holds the first “Matsuri: A Festival of Japan” at Heritage Square.

1986 Phoenix and Himeji, Japan, begin collaborating on plans for a Japanese Friendship Garden in the Margaret T. Hance Park in Phoenix.

1988 President Ronald Reagan signs Civil Liberties (Redress) Act.

1990 US Census counts 6,302 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

1996 Japanese Tea House and Tea House Garden in Phoenix opens.

1997 “Transforming Barbed Wire,” an Arizona Humanities Council-funded project, explores the incarceration of Japanese Americans on American Indian lands in Arizona. Project includes commissioned artwork, a scholarly publication, educational activities, and tours of both Poston and Gila River sites.

1999 Colorado River Indian Tribes designates forty acres for Poston educational site. Japanese Friendship Garden in Phoenix dedicated by Himeji and Phoenix city officials. Premiere of Lane Nishikawa’s play “Gila River” at Gila River Arts and Crafts Center.

2000 US Census counts 7,712 Japanese Americans in Arizona.

2002 Poston Memorial Committee dedicates memorial at former internment site.

2003 Japanese Americans in Arizona Oral History Project begins with grant from Arizona Humanities Council. Dedication of Henry “Hank” Oyama Elementary School in Tucson Unified School District. World War II MIS Veteran Masaji Inoshita of Glendale inducted in the Arizona Veterans Hall of Fame.

2005 American Community Survey counts 7,214 Japanese Americans in Arizona. Mesa Arts Center opens, featuring the 1,588-seat Tom and Janet Ikeda Theater. Arizona governor declares November 10 “Kenichi Zenimura Day.”

2006 JACL Arizona hosts the JACL National Convention at Gila River. Arizona Historical Foundation creates a temporary exhibit at ASU Hayden Library, “A Celebration of the Human Spirit: Japanese-American Relocation Camps in Arizona.” JACL Arizona dedicates a memorial to the Gila River internment camps at the Gila River Arts and Crafts Center. The Pima County Sports Hall of Fame, the Nisei Baseball Research Project, and Tucson High School recognize the Gila River Butte Eagles and the Tucson High Badgers, as well as the cooperation of their coaches—Kenichi Zenimura and Hank Slagle—at “Hall of Fame Night.” The Gila River League champion Eagles in 1945 defeated the three-time state champion Badgers at the Gila River internment camp by one run in ten innings.

2007 Cynthia Kadohata’s novel Weedflower about a friendship between a Mohave Indian and a Japanese American at Poston during World War II is the juvenile category selection for OneBook Arizona.

* Karen J. Leong is one of the panelists in a presentation titled, "Enduring Communities: An Overview of Japanese Americans in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah" at the Enduring Communities National Conference on July 3-6, 2008 in Denver, CO. Enduring Communities is a project of Japanese American National Museum.

© 2008 Karen J. Leong and Dan Killoren