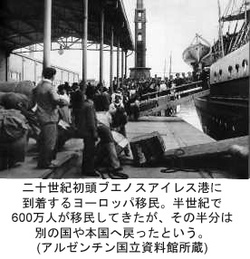

移民すると、いかなる理由があっても祖国が恋しくなるという。それが、夜逃げ同然又は政治的理由等による亡命であったとしても、経済的・社会的事情 または制度的歪みや耐え難い格差ゆえに日々の生活がままならず海外へ出稼ぎに行かざるを得なくなったとしても、半年、一年後には故郷が恋しくなる。

身分証明書等の申請書には生まれた国の欄に「祖国」とは書いておらず「出身国」、「住所」等とある。一方、日本の在留資格の申請書や市役所で行なう 外国人登録書には「出身国」、「出生地」、「国籍」、「入国日」、「再入国日(年月)」という欄を見かける。かなり長く住んでいると、このような書類に記 入する機会も多く、里帰りした回数やビザの更新回数等を思い、筆者でも「実家」に帰りたくなることがある。

日本がそれなりに居心地が良く、「第二の故郷」になりつつあっても、やはり生まれ育った出身国、祖国への想いは中々消えず、むしろ場合によっては強くなることもある。

100年、70年、50年前に北米や中南米に移民した日本人たちも同じように思ったに違いない。同郷のつながりを頼りに移民したものが多く、郷土への想いは移民先の「コロニア1」 でも反映された。リーダーたちの運営方法によっては、日本にいた時とほぼ同じものがコロニアに再現されることもある。方言や郷土料理、祭りや文化的行事等 は、新しい土地の要素や材料等(特に食材はかなりの工夫が必要だった)を取り入れながら、出身地の伝統や風習として新天地で継承されていった。こうした移 住地には必ずといっていいほど日本語学校がつくられ、移民の二世代以降は地元の正規の学校とともにこうした私塾で日本語を学んできたのである。

戦前•終戦直後の日本人移民は今のように里帰りもままならず、暮らしが少し豊かになったとしても、多くの場合は自分たちの生活改善や事業拡大(事業 転換も含む)、子供たちの教育、故郷日本への送金で精一杯だっだといえる。その分、祖国への想い、故郷へのノスタルジックは大きかったと推察できる。それ ゆえに、第二次世界大戦中は、日本にいる日本人以上に期待と矛盾を抱え、祖国を愛し応援しながらも不安は大きかったに違いない。

終戦直後のブラジルでは、敗戦のフラストレーションによって「勝ち組2」と「負け組3」が対立し、そ の結果、逮捕者と死者をも出してしまった暗い事件がある。このしこりは後にも残り、親戚・隣人同士でギクシャクした関係が10年以上も続いたという。「勝 ち組」を過激愛国者というふうに見る人もいるようだが、極端な祖国への想いが同じ考えを持たない同胞に対して武力対立にまでに発展してしまったのである。

一方、北米では(ハワイを除いて)、日米開戦を期に主に西海岸に居住していた多くの日本人移住者やアメリカ生まれの二世たちが強制収容所に送られ た。同じ敵国であったイタリアやドイツ系移民に対しては取られなかった措置だが、団結している日本人移住者は当局には「おそろしい敵」に見えたのであろ う。移住者たちからみれば「祖国日本」がアメリカと戦争になってしまったことは想定外で、大きな試練に立ち向かうことになった。また、アメリカで生まれ、 アメリカで教育を受けた「日系アメリカ人」からみれば「祖国」はアメリカで、日本は親の「故郷」である。つまり、「祖国」からは敵国人とみなされたのであ る。にもかかわらず、アメリカ人としてアメリカ軍に徴兵される者、または祖国に忠誠を誓い志願兵としてヨーロッパ前線やアジアでの諜報活動に従事する二世 らの姿があった。彼らの活躍ぶりは多くの命を犠牲に米陸軍のなかで最も多くの勲章を授章した442部隊が象徴している。ここでは、二世たちは徹底的に「祖 国アメリカ」のために戦い、その忠誠心を不動のものにしたが、中には日本を第二の故郷、親の温かい故郷と思えなくなった人もいるようになり、徹底的に「ア メリカ人」となることを決心したという。

ラテンアメリカ諸国でもペルーなどではかなり強硬な措置をとっているが、その他は幹部の一時拘束もしくは監視、新聞や学校の閉鎖という措置はとっているが、北米では南米の日系人とはまったく異なった生き方をせざるを得なかったのである4。

今の日本にはこうした過去を殆ど知らない南米の日系人―筆者はラティーノ日系人と呼んでいる―が、出稼ぎ者として約20年前に来日し、今や定住化も進み永住資格を取る人5や日本国籍を取得する者が増えた。移民として日本で生きていこうとしている「日系人」たちである。

日系人ということは、ブラジルやペルー等のコロニア(移住地)や都市部で生まれ育った日本人移住者の子孫である。こうした移住地等では日本想いの日 本人移民一世から日本語を学んだ彼らではあるが、日本では日系人たちは日本語だけではなく、日本の伝統行事やお祭り、しきたりや風習をかなり理解している ではないかと思われがちだ。しかし、移住先の国や地域にもよるが、南米ではかなり徹底した移民の同化政策(義務教育と兵役義務制度)を取ったところがほと んどであるため、日本に対して移民特有の第二の故郷という概念はあっても、当然出身国が祖国、故郷、住まいなのである。

80年代後半以降、隣国以外へでもほぼ誰にでも渡航が経済的に可能になり、南米諸国の経済危機と日本のバブル成長による人手不足が相まって、多くの 日系人が出稼ぎに来るようになった。日本政府は、日本国籍を持たない日系人に対し(重国籍を持つ者もいる)、日系3世まで(日本人の子供とその孫)に在留 資格を付与し、特別なビザを与えた(1990年の入管法改正以降)。このビザは無限に更新可能で、永住権も後に取れるようになっている。また、職種に制限 が無いというメリットもある6。

しかし、日本にいる日系人の多くは、日本語をあまり理解できず、日本人が思っているほど日本の価値観や習慣も知らない(外国人集住都市に住んでいる 者はあまり必要性がないため、覚えようともしない)。日系人とはいっても、出身国によって混血率も高く、外面的にはあまりピンと来ないかもしれない。ま た、連れの配偶者もかなりの割合で非日系人であるということが多い。当然、彼らは立派なブラジル人、ペルー人、アルゼンチン人であり、国籍という法的身分 だけではなく、文化的にもラティーノと言った方が良い。とはいえ、日本人の血が入っている以上、日本を第二の祖国と思う者、日本をいとしく思っている者は いる。日常生活の中ではあまり感じることはないが、日本との精神的な繋がりは多少残っているのだろう。

また、ペルー人の中には、便宜上日本国籍を取得し、「日本人」になる者も増えている。生まれ育った「祖国」はペルーだが、今の「国籍」は日本。現在 の住まいは神奈川県で、リマ郊外に「実家」がある。たまには「本国ペルーに里帰り」をし、「故郷」の味(料理)を満喫、残った親兄弟等とリラックスした一 時を過ごす。ビジネスで成功している者は、「居住国」が日本でも、「活動国」が日本と他の国、世界なのである。

60年前の「祖国」、「里帰り」とはその受け止め方がかなり異なってきている。移動が便利になった分、出身国・祖国への強い想いは薄れ、逆に多数の居住国・活動国が存在するようになった。故郷への想いがあっても「祖国」への想いはかなり変わってきているのかもしれない。

注釈

1. 植民地:移住者たちが居住した居住地区。日本国の支援によってつくられたものもあるが自分で開拓してつくったものもあり、南米ではあまり政治的な意味合いはなく「移住地」の類似語として使う。

2. 日本が戦争に勝てると信じ、その降伏を認めなかった日本人移住者。

3. 日本の降伏を事実として認め、以降も力強く移住先で生きていくことを決心した移住者。

4. これに関しては様々な文献や証言があり、日系人によっては大きな試練であった。11万2千が内陸の強制収容所に収容され、それまでの職と財産を全て失い、 最終的には戦後国家賠償の訴訟にまで発展し、大統領の謝罪文と2万ドルの賠償金が与えられた。ペルーからも1.771名が米国に強制送還から、そうした収 容所に移送された。

5. 永住資格者を取るものは、ペルー人の場合30%超(2万2千人)、ブラジル人の場合22%弱(7万人)である。この傾向は増えており、数年後は登録者全体の半分近くは永住ビザを取得すると思われる。

6. このような優遇処置は、筆者の出身国アルゼンチンでもよくみられる。スペイン人やイタリア人の子孫(孫の世代まで)が祖父母の国籍を取得してヨーロッパに出稼ぎに、又は留学に行く例は良くみられる。

© 2008 Alberto J. Matsumoto