“Who believes today that war can be abolished? No one, not even pacifists. We hope only (so far in vain) to stop genocide and to bring to justice those who commit gross violations of the laws of war… and to be able to stop specific wars by imposing negotiated alternatives to armed conflict.” –Susan Sontag 1

The war with Iraq and the current political climate casts a gray pall over the possibility of a peaceful resolution in the Middle East. However, one artist comes to mind as a constant believer in and initiator of antiwar and anti-violence activism even in the most negative of times.

Yoko Ono is like the wind rustling through the trees: at times, she is invisible to the public eye; at other moments she emerges as a thunderous spokesperson for peace. Ono was integral in developing the avant-garde art movement which, compared to her collaborative works with John Lennon, went unnoticed by most of mainstream media. The war with Iraq has instigated a whirlwind of activity for Ono as she has led several peace endeavors; some were anonymous projects. The wind never tires, nor does Ono’s pursuit and efforts for peace.

Her first name translates as “ocean child,” aptly describing her trans-Pacific childhood in America and Japan. Ono experienced World War II in Japan’s ravaged state as well as post-war terror and uncertainty in America. This transcontinental experience informed her perception of world relations at a young age. Seeing both sides of destruction in Japan and the United States furthered her passion for and pursuit of peace.

In order to understand Yoko Ono’s peace initiatives, lineage to her roots in the late 1950s group, Fluxus , is imperative to note. Ono was one of the first members of this international avant-garde group, which radically dissented against the traditions of modern art. The term “Fluxus” is the literal Latin translation of “flow” or “change,” which correlated with the transformation in art practices around the world and for many post war countries, a re-examination of national identity. Ono and many other contributors to the Fluxus movement fluidly crossed disciplines and often addressed social and political issues; during this time, she produced experimental performances, musical compositions, poetry, and art linked to Zen Buddhist philosophy.

Dadaist poet and critic Takiguchi Shuzo once wrote: “Poetry is not belief. It is not logic. It is action.” 2 During her involvement with the Fluxus movement, Ono developed a series of pieces entitled “instructions,” which consisted of a simple enactment of a banal activity or a set of directions for the viewer to complete. In one of the earliest performances, “Lighting Piece,” (1955), the artist appeared on stage, lit a match, and asked viewers to watch the burning flame until it disappeared. The score version of “Painting To Be Constructed in Your Head,” (1962) is another sequence of poem-like commands written in Japanese on a piece of paper. The directives begin with imagining a square canvas and then changing it into a circle. The artwork is formed solely in the viewer’s mind.

Ono often executed performance pieces outside of traditional theatre settings. In July of 1964, Ono developed a three-day program titled, “Evening till Dawn.” A Kyoto Zen monastery, Nanzenji, opened its doors to Ono and her collaborators, Anthony Cox and Al Wunderlich, for a portion of the event. Roughly 50 people gathered at the temple gate. Each was given a card with the instruction: “silence.” Later the participants received the word “touch” on another card as they entered the garden. Some enacted the instructions physically, while others mediated on the word. These early endeavors prompted audience members to use their consciousness to create the artwork or participate in the performance. In many instances, the viewer became a central component to the final piece. Dissolving the wall between art and audience became a mode of practice for Ono and played a key role in her later bed-ins for peace and billboard campaigns.

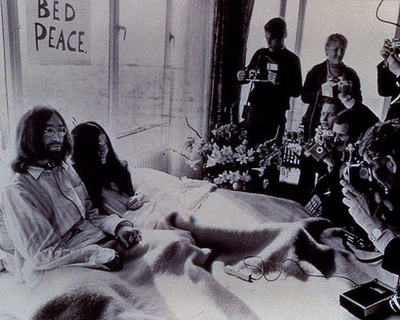

While Ono’s name was known in the avant-garde art community, she was practically unknown by much of the public. Her later works and collaborations with musician John Lennon instigated a change in her audience as well as a concentrated effort on the peace movement. After Ono married Lennon in 1969, they turned their honeymoon into a truly unexpected event. At a Hilton suite in Amsterdam, the couple stayed in bed for a week, dressed in white pajamas, and spoke to anyone on the topic of peace.

The duo attempted other bed-in demonstrations in New York and the Bahamas, which never materialized. However, in Montreal, Canada, at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, they appeared once again for another seven days of interviews and discussions. The bed-ins gained significant attention from the media as well as a large number of artists, fans and activists who flocked to their bedside. The bed-ins are considered protests against the war, however, they also carry a theatrical quality. All who came to Ono and Lennon’s bedroom that week took the role of voyeur and performer on some level, a role which connected the bed-ins to Ono’s early avant-garde performances.

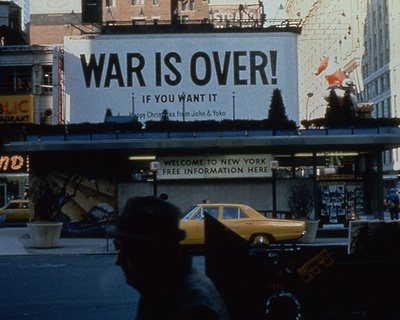

Following the bed-ins for peace, Ono and Lennon launched several other anti-war initiatives, including a billboard campaign. In 1969, a Manhattan billboard placed in Times Square read: “War is Over! If you want it. Happy Christmas from John and Yoko.” Afterwards, similar posters appeared in London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, Athens, Tokyo, Los Angeles, Toronto, Montreal and Port-of-Spain. Since then, Ono has continued this sentiment by purchasing a full page New York Times advertisement with two words, Imagine, Peace… Spring 2003.” In both newspaper and billboard form, the printed black words on a blank background are a stark contrast to the clutter of competing posters, neon signs, and displays. Logos and decorative elements are missing, making the message clear and pronounced. The advertisements remove any trace of the artist’s hand in the making of the work, akin to Ono’s earlier “instruction” series. In the billboard campaigns, the art does not lie in the physical object but in the viewer’s participation as they imagine peace in their minds.

As a child, Ono received formal training in classical piano, continuing until the age of twelve or thirteen. Her father also played the piano as a professional before pursuing a career in banking. Ono performed experimental and surreal music compositions and later developed a pop aesthetic after meeting Lennon. “Ono’s music was a bridge – if not the bridge – between the avant-garde and rock,” notes Edward M. Gomez in the catalogue for YES Yoko Ono 3 , a retrospective exhibition organized by Japan Society, New York.

The recording “Give Peace a Chance,” developed during the Montreal bed-in, was released by The Plastic Ono Band with scores such as “John, John (Let’s Hope For Peace)” written by Ono. Her last album in the 1980s, “Starpeace,” refers to Ronald Reagan's “Star Wars” missile defense system. The cover features the artist holding the Earth in her hands and smiling. Ono toured “Starpeace” to mostly Eastern European countries in order to spread the word about world peace.

In 2002, Ono inaugurated the first Grant for Peace award by donating a $50,000 prize to Israeli and Palestinian artists. Israeli Zvi Goldstein and Palestinian Khalil Rabah were the first recipients. The United Nations gathered in Geneva, Switzerland, for a celebration of the event. Artists living in areas of warfare and conflict will be considered for future grants.

Ono’s involvement in the avant-garde movement informed and contributed to her approach to promoting peace. She developed the concept that peace does not always start with action, but imagination. In this, she was revolutionary.

Note:

1. Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others , (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003) Pg. 5.

2. Takiguchi Suzo, (1931), quoted in Dore Ashton, Isamu Noguchi East and West , (New York: Knopf, 1992), Pg.89.

3. Edward M. Gomez, YES Yoko Ono , “Music of the Mind from the Voice of Raw Soul,” (New York, Harry N. Abrams, 2000) Pg. 235.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage vol. XVII, no.2 (Fall 2005), a journal of the National Japanese American Historical Society .

© 2005 National Japanese American Historical Society