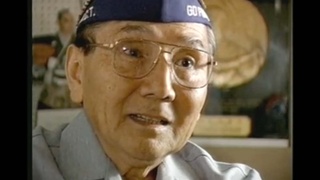

Interviews

Documenting family history for future generations

Since it’s so difficult to talk about it (camp experiences), I’ll write something for just the family. I’ll do a memoir just for the family so that my nieces and nephews can know about this part of our history. Because I had, at that time, 37 nieces and nephews. And 7 had been born in camp and didn’t know anything about it. So I tried to write but I was crying all the time and I really was in trouble, so I said to my husband, “Jim, I’m having a tough time with this project.” And he says, “What project.” I said, “Well I’m trying to write this memoir about my family in camp.” And he says, “Well tell me about it.”

Because I had known Jim 20 years at that time, we’d been married 15 and I’d never mentioned camp to him. He knew of some camp in my background but he barely knew the word “Manzanar” but it was this huge secret that I never…it was so deeply buried that I just couldn’t talk about it. So I then began to tell him and he was so shocked. So stunned. He says, “You mean, I’ve known you all these years and you’ve been carrying that around with you?” He says, “My god, this is not something just for your family. This is a story that every American should know about.” He said, “Let me help you write it to get it down.” Because that was very important.

You know, when you go through an emotional…when you have a cathartic experience. It’s very hard to do it yourself because what you do is you become ingrained in the suffering of it and you go over and over it. I mean I know because I wrote a book with a Vietnam vet. And you know, it really takes a lot of guidance to get them to talk about or, you know, myself about something that seems very minimal to me but was very powerful stuff that my husband knew that that was where it was going to be gold in the wound, so to speak. That’s why it took us a year.

And, boy, he was the cheapest shrink that, you know, I could ever have. And that began the healing but then it wasn’t until the 80s that we discovered what it was about. It was post-traumatic stress syndrome and that’s what happened to most of the Japanese. It was too unbearable to recall it because they were afraid of reliving the pain of that experience and breaking down or being…get too angry, you know.

That happened to me so many times when I would go out and give talks. And a Japanese person would come up and say, “You know, I didn’t have that feeling at all. You know, I had a great time in camp.” And then I just would look at that person and I would ask them a question. “Well, what did your family do?” or something and touch upon something and they would burst into tears right there. And shocking themselves because they just hadn’t allowed themselves to really feel. You know, it’s very humiliating to acknowledge that you were a victim. You know, it’s humiliating. So you don’t want to say, “They did…we allowed them to do this to us.” So that’s very hard to do. But once you are able to recognize that this happened, and that you’re not a victim because you can rise above it.

Date: December 27, 2005

Location: California, US

Interviewer: John Esaki

Contributed by: Watase Media Arts Center, Japanese American National Museum