Yukiko Furuta was not a picture bride and she did not remember meeting any picture brides in the area. Her marriage was arranged by family and friends.

Japanese women arriving at the "Ellis Island of the West," California's Angel Island Immigration Station. By 1920, an estimated 6,000 to 19,000 Japanese "picture brides" were processed through Angel Island. (Photo, www.angelisland.org)

C.M. Furuta—who had been living in America since 1900—traveled to Japan to meet his prospective bride. “…One day this lady asked her to go to a public bath house with her,” explains the translator for Yukiko Furuta’s 1982 oral history interview with CSU Fullerton history professor Arthur Hansen.

“When they finished taking the bath, this lady told Mrs. Furuta, ‘Go home before me and if some guests come to your house, please serve them an ashtray and a cigarette set.’ She didn’t realize anything, but she went home,” Yukiko recalled through the translator, “And, as this lady suggested, two men guests came to her house. One of them was Mr. Furuta and the other one was a go-between…that was the first time she met Mr. Furuta.”

C.M. Furuta was 31 and Yukiko Yajima was 17. Like Yukiko, C.M. Furuta was originally from Hiroshima. Her family was Samurai, but like many Samurai in the late early 20th Century, post Meiji Restoration, their financial situation was diminished. The prospect of going to America with a man of good reputation was an opportunity for her to have a better life.

“She says she was told by the other people that Mr. Furuta was a very good man,” relayed the translator, “So if she would follow him, there would be nothing to fear and nothing to worry about. So, she trusted him and just came to the United States without any fear at all.”

They married in a traditional country wedding in Japan and then made their way to C.M. Furuta’s home in Wintersburg, first arriving in San Francisco.

Yukiko didn’t remember the exact date, “but remembers that they celebrated Christmas on the boat. They stayed at Reverend Terasawa’s house (an Episcopalian, he would later become a founding pastor for the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission in 1904)…she came in a Japanese kimono. Reverend Terasawa’s wife took her to a Market Street store and bought her a Western dress to prepare her for the life here.”

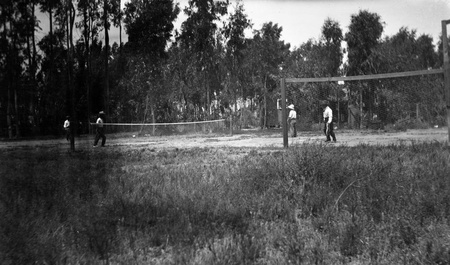

Yukiko recalls C.M. being very protective and riding her around perched on his bicycle, even though “it must have been very heavy for him.” She did not venture out on her own much, spending most of her time keeping house and later tending children at their home on Wintersburg Avenue. The Furutas invited friends over on Sundays to play go. Since C.M. did not drink sake with the men, they stayed in and played uta-garuta—a Japanese poetry game. C.M. constructed a tennis court on their property, a sport Yukiko had enjoyed playing in Japan.

The Furutas and friends playing tennis on their farm in Wintersburg, circa 1920. (Photo, www.HistoricWintersburg.blogspot.com, courtesy of the Furuta family)

Later, C.M. and Yukiko became matchmakers. C.M.’s good friend Henry Akiyama had seen a photograph of Yukiko’s younger sister, Masuko, at the Furuta house. Yukiko wrote to her parents, who gave their consent for her little sister to travel from Japan to San Francisco for the marriage. For a while, they all lived together in the same house in Wintersburg.

Both the Furutas and the Akiyamas later had successful gold fish hatchery businesses (see Goldfish on Wintersburg Avenue).

About 60,000 Japanese—many picture brides—came through northern California’s Angel Island Immigration Station. Unlike C.M. Furuta, many Japanese men in America could not afford the trip to Japan to find a wife. During the same time period, Greek laborers in Utah also began sending for picture brides. For these men, sending a photograph and information about themselves to family or friends in the old country was the early 20th Century version of Match.com. They only knew each other through letters and photographs, before meeting face to face.

By 1920, Japan stopped issuing passports to picture brides due to its negative perception in the U.S. By then, young Japanese Americans were beginning to figure out the American dating game. Once again, the Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church was a focal point in this new social scene. Congregant Clarence Nishizu recalled in his 1982 oral history interview that although “most of us were young and still in our shy stages,” the Wintersburg youth group attended local dances and social functions together, and most of them had dates.

* The oral history interview with Yukiko Furuta was conducted on June 17 and July 6, 1982, in the Furuta family home in Wintersburg (Huntington Beach) and with Clarence Nishizu on June 14, 1982 by Arthur A. Hansen for the Honorable Stephen K. Tamura Orange County Japanese American Oral History Project, jointly sponsored by the Japanese American Council of the Bowers Museum Foundation [Historical and Cultural Foundation of Orange County] and the Japanese American Project of the California State University, Fullerton, Oral History Program. Read the full interview for Yukiko Furuta at http://texts.cdlib.org/view?docId=ft7p3006z0&doc.view=entire_text and the full interview for Clarence Nishizu at http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb009n977b&query=&brand=calisphere

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on February 27, 2012.

© 2012 Mary Adams Urashima