In this life we are the protagonists of a number of stories, but in many instances the actors remain unknown because their recollections have not been recorded.

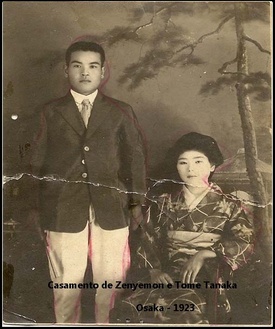

My maternal and paternal grandparents were born and lived in Osaka and Tokyo until the 1930s, when they came to Brazil to work in the coffee plantations.Sizuyo, my mother, currently at the age of 89, is the only “living memory” of her family as well as my father’s. When she turned 70, she expressed the desire to record her recollections about their migration to Brazil and the hard times they experienced, so their descendants could get to know her life story. The task of transcribing it into Portuguese fell to me, her daughter.

We want these young people to trace for themselves a successful path built on education and hard work, and to bring to future generations the tenacity, the perseverance, and the optimism of their Japanese parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents, who are the actors in this story.

Port of Kobe, July 1936

After many arrivals and departures, sailing through different oceans and crossing different continents, we finally arrived in Brazil on August 29, at the Port of Santos in the state of São Paulo. There were more than 1,000 immigrants, including adults, youths, and children, carrying only the essentials to start a new life in Brazil. After so much time looking at the sea, my sisters and I could hardly wait to get off the ship and continue our journey, this time on land.

After disembarking and spending the night at the Immigrants’ Inn in the capital of the state of São Paulo, we were taken to a wood-burning locomotive that moved slowly. I remember that the scenery I saw out the train window was very different from the landscape when traveling in Japan.

From time to time, many families would get off at the train stops, letting tears silently roll down their faces at the moment of saying goodbye. The tears reflected the pain of separation and the fear of an uncertain future for everyone. The children remained oblivious to these displays of emotion, as they took in the landscape, the people, and the animals. Everything was new to them.

The food served on the train seemed very strange to me. Later on, I learned that they were bologna sandwiches. I have a vague recollection of seeing men locking the wagons with keys and then padlocking them. Today, as I remember these things after many years have passed, I wonder if these were measures aimed at providing increased security to the immigrants or if they were measures to prevent their escape.

We got off the train in Monte Azul Paulista, the final stop on the railroad tracks. After that, we traveled by truck to our destination, the coffee farm.

The house, built out of wood, was very rustic and looked nothing at all like our house in Osaka, which had two stories and was quite comfortable. We had to get water from a cistern and from a spring, the mina de água (lit., “water mine”). The eating habits of the Brazilians, the gaijins, seemed very strange to us, consisting of rice, beans, and salt-cured beef with potatoes.

Families that had brought seeds with them began growing radishes, turnips, carrots, and chard for family consumption.

Because of the difficulty in communicating in Portuguese as well as the heavy work, which began at sunrise and finished only when the sun set late in the afternoon, we had almost no contact with our Brazilian neighbors. The goal was to get rich and go back to Japan, or be the owner of your own piece of land.

I got married when I was 17. Following a custom among immigrants, the marriage was arranged according to the miai system, in which the nakodo godfather introduced the bridegroom and future husband to my father and, with his consent, the ceremony was held at the end of the harvest. My mother-in-law said that she only got to meet the groom at their wedding ceremony.

In Japan, it was customary for the eldest son, the tionan, to live with his parents after the marriage, holding the father as the highest authority in the family. Married women owed obedience to their husbands and in-laws. Following this tradition, I moved in with my mother-in-law and my brother-in-law; my father-in-law was already dead. While the men worked in the fields, my mother-in-law and I took care of the vegetable garden and raised pigs and chickens.

The house we live in was made out of rustic wood and offered no comfort. The wood logs for cooking and to heat the ofurô (“hot bath”) came from the neighboring forests. The immigrants adapted the ofurô bath, an old Japanese custom, by using a drum to heat the water. In addition to personal hygiene, the bath helped to relax the body after a hard day’s work.

We had no electricity in the house. We got it only in 1952, when we bought a radio to listen to São Paulo’s Rádio Cultura, which aired programming for the Japanese community in Brazil.

We were neither settlers nor employees. As sharecroppers, the family grew cotton, rice, and corn. All the work was done manually, from plowing with draft animals and planting the seeds, to removing the weeds growing in the middle of the plantation. It was all very tiring. Of the total harvest, 30% went to the landowner as payment for the use of the land.

Throughout the year, we bought “on credit” at the store on the farm; the payment was made after the harvest. When someone in the family got sick, the doctor for the employees and settlers was the one who took care of them. Sometimes we attended the farm’s club to watch Laurel and Hardy movies. We traveled by train or truck whenever we needed to go into town.

During World War II, we didn’t receive any news about the Japanese fighting alongside the Germans and Italians against the other countries involved. At that time, many Japanese immigrants were discriminated against and persecuted as spies by the Brazilian police.

It has been almost 80 years living in Brazil, the first twenty years in the countryside. I don’t miss those times, as those years were very difficult. But today, as I remember the past, I consider myself a happy person. I have all the necessary comforts. My children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren live in another reality and they can’t even remotely imagine the life that my sisters and I experienced as immigrants.

Recently, I drove by the place where I lived 70 years ago. In my mind, I expected to see the house, the vegetable garden, the orange trees, the mango trees, the banana trees, the fence that separated the orchard from the garden, and the pond at the end of the backyard. But what I saw instead was just a dam in the midst of an orange grove, and the scene lasted only a few seconds because the speeding car soon left it all behind.

What caught my attention were the eucalyptus trees that had been planted back then. I see that they are still there, standing tall and leafy, forming a large, shady corridor for those entering the property. They haven’t been destroyed; on the contrary, they are increasingly present, challenging the passage of time for more than seven decades.

The Sansei, Yonsei, and Gosei descendants of the Nakanishi and Tanaka families are young people who dream of a future of success and happiness for themselves. They value education and hard work, aware that these form the all-important basis for the realization of their dreams. Alongside their professional and educational activities, they spend time with other young Nikkei. Many of their friends have been or are now working in Japan as dekasegi.

The Brazil that welcomed me in the past is now the home of my descendants. Passed down the generations, this patriotic spirit has led to a very strong desire among these young people to feel Brazilian. We just don’t want them to forget their roots…

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of their favorite Nikkei Family stories.

Comment from Celia Sakurai:

Kiyomi Yamada Nakanishi’s My Life, Our Life: The Present, The Past, and The Future follows the trajectory of her mother, Sizuyo, who arrived in Brazil at the age of 10, and who is now 89 years old. Her main concern is to leave a record of her memories for today’s youth: “Do not forget your roots.” Although the place where she lived has undergone changes leaving it almost unrecognizable today, there still remain the eucalyptus trees planted by the family decades ago. The trees, like Sizuyo’s story, are the link connecting the different generations, giving meaning to the present for both the protagonist of the story and her descendants.

© 2015 Kiyomi Nakanishi Yamada