My first introduction to Nina Revoyr’s writing was through her 2003 novel, Southland, a story of love, family, and hopes interrupted by forces of hysteria and racial hatred. Told from multiple perspectives during 1994, WWII, and the Watts Riots, Southland shows readers a Los Angeles of shifting borders and poignant history.

All of Revoyr’s four novels share an incorporation of regional history, atmospheric prose, and complicated layers of race and sexuality that the author never treats with a heavy hand. The most remarkable aspect of Revoyr’s writing, though, is the warm, steady voice she allows her narrators, their worldview always in the end optimistic in the face of emotional exhaustion.

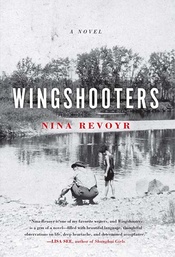

Her most recent novel, Wingshooters, is the story of Michelle LeBeau (called Mikey), who like Revoyr is the daughter of a Japanese mother and white, American father. Brought to Deerhorn, Wisconsin to live with her grandparents, Mikey becomes the obvious outsider in an all-white town. Though ostracized and bullied at school, she finds happiness with her dog Brett and loving grandfather Charlie, a man whom everyone in the community respects.

When a black couple moves into town from Chicago, Mikey becomes less of an outsider by contrast. But the Garretts’ presence rocks the community in ways that a young child could never predict in a 1970s Midwest that has yet to embrace the changes brought about by the Civil Rights movement. In the end, Mikey finds herself at the center of a tragedy that changes the way she views her grandfather, herself, and the world around her.

Revoyr and Mikey share a few more life details beyond ethnic background. Born in Japan, Revoyr spent much of her childhood in Wisconsin, lived in Los Angeles through high school, then spent some time in Japan and on the East Coast. In 1998, she returned to California to stay.

In anticipation of her February 25 reading with Margaret Dilloway (How to Be an American Housewife) at the Japanese American National Museum, I asked Nina Revoyr to speak a little about her work and her cultural identity.

I know that you’ve lived in both Los Angeles and Wisconsin, so how much did your own family’s experience inspire your work in Wingshooters and Southland?

Southland wasn’t influenced by my family’s experience at all—at least not in the direct ways you might imagine. The Japanese side of my family was in Japan during World War II, not the U.S., and so the whole experience of internment—not just during the war years, but also afterwards—was not something I had direct knowledge of. The book really grew out of my emotional connection to the Crenshaw area, and all it represented. The Japanese-American and African-American residents there were like older version of my friends and me. I basically imagined a familial history there—but the fact that people assume that Southland is based on my own family history is, I think, a compliment.

The set-up of Wingshooters is much more based on real-life circumstances. My dad—who fortunately is nothing like the dad in the book—did grow up in Wisconsin, meet a Japanese student, and then move to Japan. I did spend part of my childhood in rural Wisconsin, and face the kind of prejudice that Mikey encounters. But while the bones of the situation are from real life, the story itself is totally fictional.

Wingshooters turned out to be a much heavier story than I would have expected with a child for a narrator. What inspired you to write about such events? How did you decide to show it through the eyes of an adult looking back on her childhood?

I wanted the immediacy that was possible by describing events through the unaffected, unfiltered eyes of a child. But I also wanted to provide the larger context in which those events took place. A kid may not be able to appreciate how the Boston bus riots or the Vietnam War stoked social and racial tensions in the Midwest—but an adult could provide that perspective. And having an adult narrator also allowed me to show how childhood events, especially traumatic ones, shape the person that one becomes.

Do you have any particular feelings about the word “hapa”? How do you identify yourself ethnically, if you do at all?

I don’t have any particular feelings about the word “hapa.” But I do have feelings about racial identity more generally. I identify as Japanese-American, and mixed-race, but I don’t really focus on being biracial as an identity in itself. Sometimes when mixed-race people with one white parent make a point of identifying as biracial, it feels to me like they are trying to get away from their non-white side. I have no desire to do that. But in addition to identifying as Asian-American, I also think of myself as part of a broader community of people of color. I’ve spent much of my life in social contexts that are largely African-American and Latino, and when I was growing up, my black and Latino friends gave me the language to talk about race. My spouse is Mexican-American. So I feel a real connection with people of color more generally.

But in addition to all that, I’ve realized in this last year, with all my traveling for Wingshooters, how deeply shaped I was by the Midwest, and by a certain blue-collar sensibility and set of values. The most nurturing figures in my family, my father and grandfather, were Midwestern white men. So—a lot of different elements have gone into my making, and I feel lucky to have had such disparate influences.

Where do you feel the most at home now?

In terms of people, I feel most at home in neighborhoods or environments that are truly mixed race. I like environments that are reflective of the world as I know it. So Los Angeles is still the place for me—I love it here, it’s family, even when it’s annoying or infuriating. Physically, though, I feel most at home in the natural world. And I’m happiest in total wilderness, in the mountains.

Have you noticed any racial or ethnic trends among your readers?

For my first three books, my readers were largely people of color and progressive whites. Not surprisingly, maybe, given their settings and topics, those books tended to have a lot of Asian-American and African-American readers especially. The books also had readers of all races who enjoyed history, or who were interested in Los Angeles.

With Wingshooters, there were all those same readers, but then a whole new faction of white readers—not just politically progressive folks, as you might expect, but also self-proclaimed conservatives. I think people really latched onto the Charlie character, and his blend of goodness and prejudice. The book seemed to give people a way to talk about race, and often people from totally different sides of the political spectrum would show up at my events. This was very moving to me—it made me realize how rarely people of different political beliefs actually sit down in a room together, and how important it is that they do so.

Which of your books was the most fun for you to write?

They were all fun at points. Not that they weren’t also hard work and exhausting and never-ending at times. But there always has to be an underlying sense of enjoyment for me, or else deep purpose. Otherwise I can’t force myself to do it. And when I am forcing it—when it consistently feels like a slog and I can’t bring myself to really care about the characters or the story—then I listen to that, and stop. Although I do believe that writing is largely, as they say, about perspiration, I also think that inspiration is vital. If you’re not inspired as a writer, if you don’t really care about what you’re writing, then why should anyone else? There are too many books and stories out there already that might be technically proficient, but lack passion. If I don’t absolutely need to be writing something, than I shouldn’t be writing it. I have to follow what’s most intriguing or meaningful for me. Otherwise, why bother?

Do you have any upcoming projects you can tell us about?

I do have something going, but it’s too early to discuss it. It is, as usual, very different than the last book. I’m only at the very beginning stages—but I’m having fun, and that’s all I can ask for now.

* * *

Nina Revoyr and Margaret Dilloway will read from their most recent novels at the Japanese American National Museum on Saturday, February 25, 2012 at 2:00 p.m. Readers will have the opportunity to meet both writers and have their books signed after the reading. For more details >>

© 2012 Japanese American National Museum