After leaving the Visual Communications (VC) after seven years of great experiences with Bob, Eddie, Duane & Alan Kondo, among many others, I entered U.C. Berkeley’s 3-year graduate architecture program in 1977. An intensely sought-after opening for some twenty-plus students per year, it was an immersion process where, for the entire first year you spend with the same group of students developing design solutions with a rotating group of professors.

I went in thinking that I would combine film and architecture, but soon realized I just loved the design process itself. My work at VC served me well, having done a lot of graphic design similar to photographic and other processes necessary for our design presentations I already had mastered. During school I supported myself as a graduate assistant. This allowed me to meet and get to know a lot of the faculty, which was a plus. I helped two professors who were very deep into Japanese garden design by printing their photographs for a book they eventually published on the subject.

Before graduation I worked at the ELS Design Group in Berkeley, and on one project worked under Ken Kaji, a senior architect, on the U.S. Embassy staff housing in the Philippines. He was like a mentor to me, and when we parted ways in 1985, we did not know that we’d work together again on the MIS project.

I had a lot of fun at the ELS Design Group and eventually became a lead designer responsible for the U.C. Press Building headquarters building. They were moving into an old furniture warehouse ill-suited for their offices, but with a lot of work it became an award-winning project. I got to fly to New York with my boss to receive a national design award at the Plaza Hotel in 1983.

Many years later in 1998—by then I had started my own architectural practice, Ohashi Design Studio—Ken Kaji contacted me about meeting Rosalyn Tonai (Roz), Executive Director of the National Japanese Historical Society (NJAHS), and possibly working on a historic conversion project in the Presidio of San Francisco. Ken was now on the Board of Directors for NJAHS and knew of my background at VC and thought I would be a good fit for this project. Roz and I met and walked through Building 640, an aircraft hangar built in the 1920s that served as the classroom and barracks building for the first class of Nisei soldiers to serve as linguists and interpreters in the potential upcoming war with Japan in November of 1941. Roz mentioned that when she was in college someone gave her the book I worked on, In Movement: A Pictorial History of Asians in America—that Dr. Franklin Odo wrote and Glen Iwasaki designed. We of course pulled the images from the VC archives.

General DeWitt, the same man who formulated and signed Executive Order 9066, conceived of identifying Niseis and non-Niseis who had Japanese language skills, and bringing them to the Presidio to be trained as top-secret counterintelligence operatives under the umbrella name of the Military Intelligence Service which today is known as the Defense Language Institute based in Monterey, California. I visited his office, which is kept as it was in the 1940s, and located less than a mile from Building 640.

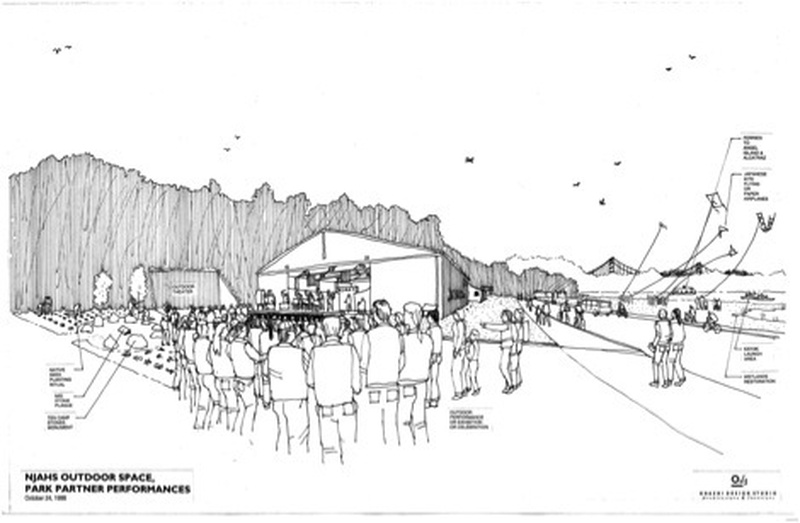

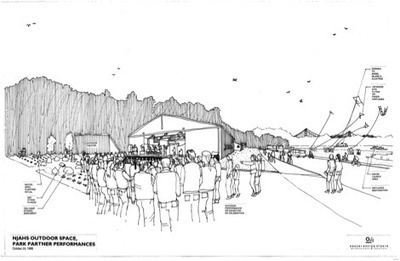

After touring Building 640 with Roz, the NJAHS hired me to do some promotional renderings of what the building could be, for fund-raising and other purposes.

Roz and others at NJAHS worked hard to develop relations with The Presidio Trust who were responsible for Building 640. By this time, 1998, the Trust was aware that NJAHS was the organization that grew out of the MIS veterans group, some of whom included Colonel Tom Sakamoto, who helped translate for the Japanese who surrendered on the U.S.S. Missouri, Marvin Uratsu, and Harry Fukuhara, among others. These same Nisei veterans were now pressing to make Building 640 into a museum for the MIS. The MIS, having been top-secret during the war, were now having their story come out into the open. The Trust had pretty much decided that Building 640 could only go to NJAHS because of the backstory, and worked very hard to make it happen, as did NJAHS.

I proposed a design studio at U.C. Berkeley’s School of Architecture, undergraduate program around the Building 640 project. I teamed up with Prof. Dana Buntrock, who specializes in cutting edge Japanese architecture, who thought Building 640 to be an intriguing story. We had ten students working for a quarter on design solutions. Once we made a field trip to see Building 640—it was set for September 12th, 2001—the day after the 9/11 attack. We were all in shock, but the backlash we heard against Muslim Americans echoed in our minds walking through Building 640.

Roz was able to get the support and backing of politicians Nancy Pelosi, Barbara Boxer, and Mike Honda. She also connected with Senator Daniel Akaka who was then head of the Senate Appropriations committee. I made a small presentation to Sen. Akaka and his staff and he was very complimentary toward the project. Eventually with the help of Pelosi and Boxer’s offices we secured three appropriations from the Department of Defense which allowed us to finally start construction in 2011 after many years of work.

Over the years, we had many, many meetings with the Presidio Trust who have always been very fair, clear and straightforward. They have the responsibility of keeping the historic integrity of the Presidio, a big job. Building 640 is unique among the many internment camp interpretive sites in that the original building fabric—the original concrete floors and walls from 1941 where the MIS soldiers studied and slept is still there. NJAHS eventually worked out an arrangement whereby they lease the building free of charge and pay for utilities, security, fire, and so forth. You cannot buy a building on what used to be Federal land; everything is leased.

Construction was difficult. The contractors had to support an eighty-year old structure that had been warped, racked and over-loaded in the past. It couldn’t handle the process and on December 23rd, 2011 I got the phone call from the contractor that it had collapsed!

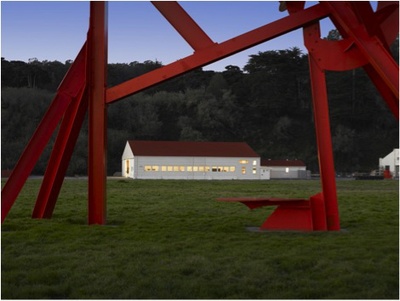

The general contractor, Oliver & Company, stepped up big time. They knew that a construction failure could end up in court for years delaying the project and costing everyone a lot of money. They knew the MIS veterans were in their 80s and 90s and delays would mean they wouldn’t be around to enjoy the results. Oliver & Company offered to accept responsibility for the collapse, pay for re-construction of a pretty much new building replicating the original and settle with their insurance company later. Anything salvageable from the old building was kept—that included the original concrete floors and foundation, latrine building, and the wood ceilings. In place of failing steel trusses, new ones made to current seismic code were installed. The original windows were stripped, cleaned up, and re-glazed.

The collapse was a mixed blessing. NJAHS received a totally new building without compromises for age or history—but we did lose an original piece of Japanese American history. But much of it lives on in the re-built Building 640.

Work on the exhibit design had been underway for years, but as the designs were too expensive for what NJAHS had left in their budget. We created—with the help of the original exhibit designers, the West Office Exhibit Design firm—a layout that could be completed piecemeal with available funds. Doug Dawkins and his company, the DRDC Group Inc. stepped in to build these two exhibits, working all night before the ribbon cutting ceremony in early November. I walked in the moment they were mounting the last flat screen monitor.

At our “soft” opening and ribbon-cutting ceremony at the building, many MIS veterans showed up as did a representative from Nancy Pelosi’s office, Craig Middleton, Executive Director of the Presidio Trust—both of whom have been very supportive of the project.

Building 640 has been a fifteen-year project for our firm. Despite the highs and lows it has been a good experience working with the Presidio Trust, National Park Service (NPS) and NJAHS. Though there was not much high design involved, the importance of the project in the history of Japanese Americans and Asian Americans is notable.

Latrines reconstruction – the latrines had the only lights on at night – the rest of the building was “blacked-out” for fear of attack so the MIS students would sit on toilets and continue their studies here

*This article was originally published on the Visual Communications blog, From the VC Vault, on December 13, 2013.

© 2013 Alan Ohashi