War brides after the war

After Japan lost the war in 1945, many American soldiers and civilian employees were stationed in Japan as the occupying forces. It was only natural that young men and Japanese women would fall in love with each other. The women who married them and went to America were called "War Brides."

It is easy to imagine how the general public viewed these women and how their parents responded to them marrying men from a country that had been despised as "devilish America and Britain" during the war. Nevertheless, they married, crossed the ocean, and walked a path completely different from the life that many other Japanese women led in Japan during the postwar reconstruction and high economic growth period.

Of course, each woman's path is different, but there is certainly a way of life that is unique to these women, who share the common thread of living in a time that spanned the "war." Photographer Tsuneo Enari has focused on these women, who are said to number about 45,000, and introduced their appearances and words through photographs and text. Born in Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture in 1936, Enari worked for the Mainichi Newspaper before becoming a freelance photographer and reporting on war brides in the United States.

The result of this was published in 1980 as "The Bride's America" (Asahi Shimbun's Asahi Camera special edition), and later published by Kodansha as a hardcover (1981) and a paperback (1984). Furthermore, 20 years after his initial interviews, he followed up on his previous interviewees again and published "The Bride's America: Landscapes of Time 1978-1998" (Shueisha) in 2000.

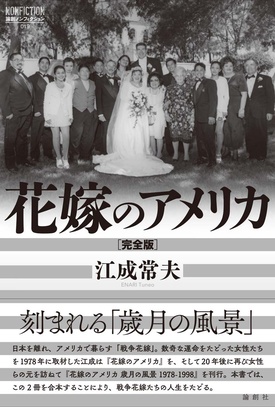

Then last year, a new edition of "Bride of America" combining "Bride of America" and "Bride of America: Landscapes Through the Years 1978-1998" was published by Ronsosha (Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo) as "Bride of America [Complete Edition]."

Visiting over 100 brides

Enari became interested in war brides in September 1975, when he visited Yoshiko Boone, a relative on his wife's side who lived in Oklahoma, and learned about her life story.

"The absurdity of an era in which women were educated to believe in the devilish Americans and British until Japan's defeat, and then shortly after the defeat, they had no choice but to work for the U.S. military to support their families. In the process, she married a U.S. military officer, and the Japanese around her ridiculed her and subjected her to prejudice - this perception of Yoshiko was also a factor that sparked interest in the brides," says Enari.

Based in a modest apartment in Gardena City, about 20 minutes from Los Angeles, the freelancer Enari has visited over 100 people across California, relying on his personal connections to find "brides." However, he doesn't always get people to agree to interviews, and even if they do, they don't always open up to him right away.

Perhaps overcoming this barrier little by little, Enari interviewed the brides about their lives and also took photographs of their families. Enari calls this method of photographing things that cannot be expressed in words, and writing down things that cannot be expressed in photographs in their own words, "photo non-fiction."

Just reading the text, which contains their exact words such as "I was born in ____ in 1930," gives one a glimpse into their lives. The content is a very personal history, but at the same time, it is also one aspect of the vivid history of Japan and the Japanese people across the war.

Not all the people appear under their real names. E.A., who was born on Amami Oshima, gave birth to a child with an army MP the year after the war ended. When she woke up, the doctor said, "Oh, he's just a delinquent's kid anyway. We don't want him." "It was a time of chaos after the war, so there was no way to sue him, and he was killed without us even knowing why." (E.A.)

After she got married, she took her next son to the market, and an old lady passing by saw the child and said, "Oh, another bullet shield has been born." She then said, "If war breaks out again, we'll send our love children like this one to the battlefield to be bullet shields -- remember that..." (E.A.). It's an unforgivable thing to say, but it's proof that the hearts of the Japanese people were also devastated.

Born after the war, N.P. married a black man who was a crew member on a minesweeper and moved to the U.S. One day, when she attended a meeting with local Issei (first generation) Japanese, she was shocked when an Issei grandmother said to her, "You have such a pretty face, but poor thing you've become a black man's wife..."

Of course, not all of the experiences were terrible. There are also stories of kindness not seen in Japanese men, and of the husband's parents being supportive. However, what is apparent throughout the book is the difficulties that befall women in a foreign land, such as the language barrier, marital relationships, and financial difficulties, and the determination to overcome them.

Times, life, destiny

I first read "The Bride's America" (paperback) in the 1980s. At the time, I wasn't particularly interested in Japanese Americans or immigrants, but I remember being drawn into the pages. Rereading it now, I feel the intersection of "the times," "the way of life of individuals," and "destiny" in the bride's words.

First of all, it was a time roiled by war. The brides spent their youth during and after the war. They lost their families, homes and property in the war, were mobilized to work in munitions factories, or were evacuated... They were a generation that sacrificed their youth to the war. Meanwhile, the American men who would become their spouses were also deeply involved in the war. World War II ended, but what awaited them afterwards was the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

Some of the brides lost their husbands in the Vietnam War. They experienced the hardships of war in Japan, and as long as their husbands were soldiers or civilian employees of the military, the shadow of war followed them. They were transferred many times due to their deployment and duties. Living apart from their families can affect marital relationships, and their husbands' alcoholism may also be related to them being soldiers.

Even though their very foundations were shaken during these times of war, they had the strength to live desperately for their families, for their children, and for themselves. In fact, they had no choice but to become strong. This was the result of their own decisions.

It wasn't that I had thought it through deeply. I was freed from the oppressiveness of war, longing for wealth, and perhaps hungry for kindness that may have been superficial. I pushed aside my parents' objections, and didn't care about what other people thought, and in hindsight I regretted making such a big decision.

But perhaps the reason they persevered was because they had a sense of pride, mixed with resignation, that it was "a decision they made themselves." This resignation could also be seen as "fate," in the sense that no matter how hard they tried, they would be swept away by the times and the environment.

In Enari's second interview, he follows in their footsteps 20 years after his first interview. Some have already passed away, and some are missing. There are also husbands left behind. Meanwhile, readers learn that their children and grandchildren have grown up and are starting new families. They are like flowers that have bloomed after much effort.

The lives of war brides, who could be considered the first generation of postwar immigrants, will likely become family history for this new generation, but for Japan, they have become a story that forms one aspect of its postwar history.

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai