At the time of his passing, Franklin was working with Honolulu attorney William “Bill” Kaneko, his former Ethnic Studies student, and journalist Sara Lin on a book about the Hawai‘i AJAs who, although not incarcerated, were forcibly displaced from their homes. Kaneko had asked Franklin to serve as the book’s editor.

Aside from his parents, “Franklin had the greatest impact on my personal and professional career,” Kaneko said. “He was my teacher, mentor, advisor and friend.” In Franklin’s Japanese in Hawai‘i class, he learned about Japanese immigration and about their history and contributions to Hawai‘i. And, for the first time, the future lawyer learned about the unlawful incarceration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast and in Hawai‘i. The civil rights violations and the lack of due process imposed upon the 120,000 AJAs who were incarcerated during World War II left Kaneko aghast.

“Franklin made history come alive. He challenged our way of thinking and evaluating events of the past and how it is relevant to current events, and he did so in a way that was kind, supportive and inquisitive,” Kaneko said.

Their relationship continued through the Honolulu chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, of which Franklin was a founding member. In 1981, he had assembled the delegation to testify about Hawai‘i’s experience before the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

“Franklin was key in ensuring that the commission knew and understood the impact that Executive Order 9066 had on Hawai‘i AJAs, in addition to the West Coast experience,” Kaneko said.

Inclusion of the Hawai‘i experiences in the larger wartime incarceration story was essential in ensuring that Hawai‘i AJAs were included as part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 and, therefore, eligible for redress, Kaneko explained.

Although they lost touch when Franklin began working at the Smithsonian, Kaneko said his mentor was never far from his thoughts. “He instilled in me the need to remember where you came from and the need to take care of those in need.”

Franklin reminded him and others of how fortunate Hawai‘i AJAs had been to have had people like Gov. John Burns and other supporters in their corner, giving the Japanese community a chance to influence politics in the 1950s and 1960s, creating an equal playing field that enabled them to advance relatively quickly in society.

He also believed, however, that AJAs in Hawai‘i have “a responsibility to care for newer immigrants and emerging communities in the same way that Burns and others did for us,” said Kaneko.

In the early 1990s, concerned that the history of Hawai‘i’s more recently arrived and less affluent ethnic groups was being ignored, Franklin advocated for the creation of a “state history center” to collect the history and experiences of all of Hawai‘i’s ethnic groups before it was lost and to empower all groups equally. For various reasons, including the proposed $64 million price tag and the concern of existing museums that they would lose their funds, the proposal failed to gain any traction and the idea died. Franklin understood the politics of government, but always remained true to his convictions.

Kaneko said he was grateful for the six months he had to reconnect with Franklin while working on his book. “While our work together was, unfortunately, cut short because of his passing, Franklin, like he had always done for me in the past, provided incredible insight on how to look at issues and history,” Kaneko said. Franklin will never know the thousands of students, friends, and colleagues whose lives he impacted, including his own, said Kaneko. Hawai‘i and America are a better place because of him, he added.

I, too, am among the “thousands” that Bill Kaneko referred to. Franklin’s perspectives on history were priceless. In 1990, the 90th anniversary of Okinawan immigration to Hawai‘i, I interviewed him on a variety of subjects relating to Okinawans, one of them being the notion that “Okinawans are a peaceful people.” Franklin cautioned against explaining characteristics in terms of “innateness” or to explain it in terms of culture. “I think Okinawans, too, could oppress other people if they had the power to do so,” he said. “It’s not that they’re innately peace-loving people.”

He underscored the importance of turning to history to understand how and why events developed as they did, including in Okinawa. The 1945 Battle of Okinawa claimed more than 200,000 human lives—military and civilians, Okinawans, Japanese, Americans, and allies—in just three months of fighting. It taught us about the human cost of war. History, not DNA, is the reason Okinawans say, “Nuchi du takara—life is precious.”

Characteristics such as “cohesiveness” and “peace-loving” are not innate traits, he emphasized: They are rooted in a historical condition. “Something happened that made it more worthwhile for people to get together and put aside their differences than to maintain them,” he explained.

In 1990, Franklin was one of 10 Hawai‘i residents (and 100 worldwide)—and the only non-Okinawan from Hawai‘i—that the Okinawa Prefectural Government named an “Uchinaa Goodwill Ambassador” for his contributions to the Okinawan community.

Although Franklin lived thousands of miles away from Hawai‘i, he always enjoyed seeing and hearing from old friends and former colleagues. Kevin Kawamoto, a gerontological social work educator, recalled his chance meeting with Franklin in New York City around 1994, just after Kawamoto had moved there.

“One day I was on the subway and I heard someone call my name. I looked back and it was Franklin. He was a visiting professor at Columbia, where I was working. I felt relieved to know that there was one person in the city who I knew, and not just one person, but Franklin Odo,” he said.

“Whether Franklin was physically present or not over the years, I have always felt his ‘presence’ due to the impact that his knowledge, wisdom, character and personality had on me from an early stage in my life and career.”

Franklin also held visiting professorships at the University of Pennsylvania, Hunter College,and at Princeton during the 1990s and served as president of the Association for Asian American Studies.

In 1997, he and Enid moved to Washington, D.C., where he had been named founding director of the Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Program and the first Asian Pacific American curator at the National Museum of American History. In 1999, he arranged for the exhibit, From Bentō to Mixed Plate: Americans of Japanese Ancestry in Multicultural Hawai‘i, curated by writer Arnold Hiura for the Japanese American National Museum, to be shown at the Smithsonian.

And, in 2002, he brought another important Hawai‘i story to the Smithsonian: Kaho‘olawe: Rebirth of a Sacred Hawaiian Island. Visibility of Asian American and Pacific Islanders’ history, arts and culture increased during his time at the Smithsonian. Franklin later served as interim chief of the Asian Division at the Library of Congress, where his knowledge of traditional Asian Studies was put to good use.

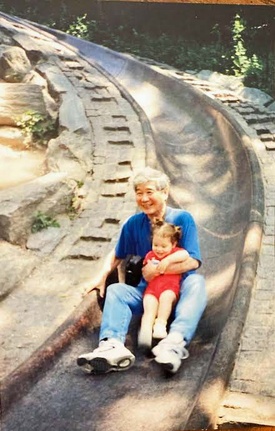

In 2015, Franklin’s love for teaching and mentoring students beckoned him back to the classroom, this time to Amherst College in western Massachusetts, where he and Enid, his life partner for 58 years, would be closer to their adult children, David, Jonathan, and Rachel, and their families.

Like Kevin Kawamoto, Franklin never seemed that far away to me, thanks in part to PBS Hawai‘i’s reprising of documentary films in which he was asked to provide a historical perspective. These included Holehole Bushi: Songs of the Cane Field, and Proof of Loyalty: Kazuo Yamane and the Nisei Soldiers of Hawai‘i. Sometimes I would email him to say hello and to let him know that one of those films had been rebroadcast. He was glad to hear that those programs were being rebroadcast to remind the community and expose younger generations of this rich and valuable history.

Proof of Loyalty highlighted the military service of Kazuo Yamane, a kibei who was born in Hawai‘i and educated in Japan. Yamane’s Japanese language abilities led to his transfer from the 100th Infantry Battalion to the Military Intelligence Service. In the film, Franklin highlighted the contradiction the government failed to grasp.

“. . . [T]he two groups of linguists that we now so treasure and revere are the Navajo speakers and the kibei (who served in the MIS). . . . We prohibited the Native Americans from speaking their own language. We systematically tried to stamp that out. We tried to stamp out the foreign language schools, the Japanese language schools in Hawai‘i and on the mainland before the war. And yet, these people became extraordinarily important in the war effort,” he said.

Despite Franklin’s full schedule, he always made time to answer my questions and to put history into perspective. For that, I am eternally grateful. He was always encouraging during my time at the Herald and even after I had retired. In late May, he wrote: “Hang in there, Karleen, we all need your voice.”

Professor Ty Kāwika Tengan, who was decades younger than Franklin, never worked alongside him. When Tengan joined Ethnic Studies in 2003, Franklin was already at the Smithsonian. They got to know each other, however, during Franklin’s visits home and corresponded more often when Tengan was Ethnic Studies’ department chair from 2013 to 2016 and again from 2019 until last semester.

Tengan said he sought out Franklin’s advice when the fiscal crisis brought on by the pandemic threatened the Ethnic Studies Department with either a merger or complete elimination, despite a growing number of majors. Franklin’s advice to organize at the local level and to draw upon national and international networks of support resulted in a commitment from the administration to sustain Ethnic Studies and approval to hire two faculty members—a specialist in Japanese American and Okinawan diasporic studies and a new director for the Center for Oral History.

“Remember this crisis and keep it as an ES institutional prerogative—leaving this issue alone will continue to put the department in peril. Don’t let friends, alumni and supporters forget,” Franklin emailed Tengan in May.

“I later learned he wrote that while battling the cancer that eventually took his life—a true fighter for Hawai‘i’s people ’till the end,” said Tengan. By his example, Franklin inspired Tengan to “put in the hard work of grounding scholarship and activism in the needs of the community, caring for comrades we are in struggle with, holding accountable leaders who are not fulfilling their kuleana and finding time to laugh at the absurdities of life that might otherwise drive us insane.” In one of his last texts to Tengan, Franklin wrote: “Too much went into ES to let it die. Needed as never before. Call on me/us.”

Aloha ‘oe, Franklin. Mahalo nui for your friendship, inspiration and conscience, and for always reminding us of the importance of “Our History, Our Way.” A hui hou . . . until we meet again.

*This article was originally published in The Hawai‘i Herald on December 16, 2022.

© 2022 Karleen Chinen