“If you don’t control your own culture and your own vision of life, and your own participation in life, then you don’t control anything. And that’s what we’re about. The true spirit of any kind of democracy is to have people be autonomous at the same time that they know that they’re dependent on the community around them.”

—Dr. Franklin Odo on empowering people and communities from a 1990 oral history interview with the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Center for Oral History

Franklin Odo was never my professor at the University of Hawai‘i, but he was the sensei, the teacher, who I always turned to with questions about Japanese American, Okinawan, and Asian Pacific American history and its impact on people. I know I was not alone.

“I often think about how he changed my life through his scholarship, activism, and teaching,” emailed Kaua‘i native Wesley Ueunten, a professor of Asian American Studies at San Francisco State University and a recent Fulbright Scholar.

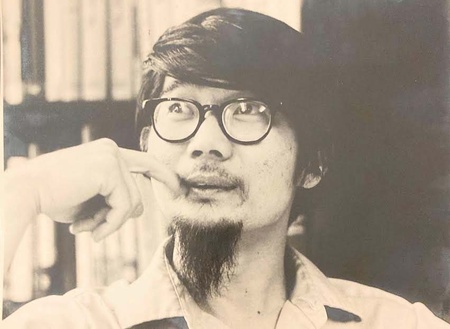

Known to more people as “Franklin” than as “Dr. Odo,” Franklin died on Wednesday, Sept. 28 at the age of 83 in Northampton, Massachusetts, due to complications from cancer. His passing is a major loss for Hawai‘i and Asian Pacific American communities worldwide.

The son of kibei parents, Franklin Shoichiro Odo, grew up in Koko Head, known today as Hawai‘i Kai, where his parents were vegetable farmers. Franklin attended Kaimukï Intermediate and Kaimukï High School, graduating in 1957.

Isami Yoshihara, his former schoolmate, recalled that elections for Kaimukï High’s sophomore class officers were held late in their freshman year. Franklin was running unopposed for president until Yoshihara’s teacher urged him to run. Franklin won 370 votes to Yoshihara’s 25. “I always wondered who were the 25 that voted for me, because I had voted for Franklin,” Yoshihara said.

Franklin was a bright and well-rounded student. He played baseball. He and Yoshihara took the same college prep courses. They were also in a YMCA club called the Ramblers and participated in many community service projects, including canvassing the Kaimukï-Kapahulu area with a petition calling for the building of an auditorium for Kaimukï High School.

In his senior year, Franklin was elected student government president. Both he and Yoshihara were selected as the student speakers for their commencement. Both also were accepted to top colleges on the continent—Yoshihara to UC-Berkeley to study civil engineering, and Franklin to Princeton, its first Kaimukï High grad to attend the Ivy League school, Yoshihara said.

“The last time I saw Franklin in our youthful days was when he and his bride left to study in Japan on an ocean liner from Honolulu in 1963 or so,” Yoshihara recalled. By the time Franklin returned to Hawai‘i to lead the UH (University of Hawai‘i) Ethnic Studies Program, Yoshihara was a civil engineer working for the federal government in Tōkyō.

Franklin was the professor we all wished we had in college: He was smart, witty, friendly, never demeaning. He had impressive credentials — bachelor’s degree in Asian Studies from Princeton, master’s in East Asian regional studies from Harvard, and his Ph.D. in Japanese history from Princeton. He could have turned into an “ivory tower” academic. Fortunately for us, he was the exact opposite.

He found his real calling in developing Asian American Studies and Ethnic Studies programs while teaching at Occidental College, UCLA, and California State University-Long Beach. He had emerged as a leader during the civil rights and antiwar movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, galvanizing students, scholars and activists to demand representation on college campuses. Franklin’s ability to read and speak Japanese were assets in understanding Japanese history and culture and their impact on immigrant communities.

In 1978, he returned to Hawai‘i with his wife, Enid, and their three young children to accept the directorship of UH-Mānoa’s Ethnic Studies Program and to also teach the Japanese in Hawai‘i course, delivering lectures twice a week and supervising a team of course lab leaders who were UH students. Professor Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor, acting director at the time, recalled that an administration review determined that a full-time tenure track professor was needed to direct the program.

“We were quite surprised when someone of Franklin’s stature applied—a ‘local boy’ Kaimukï grad, educated at Princeton and Harvard! He turned out to be the perfect choice,” said McGregor, who has been with Ethnic Studies for nearly five decades.

Franklin believed that Ethnic Studies was vital at UH-Mānoa in order to critically explore race relations and the lives of working class people and the dispossessed. He lobbied the administration for more positions and to pay the faculty a living wage while ensuring that the instructors pursue the academic credentials expected of any university faculty. It was a precarious balancing act between academics and activism and Franklin navigated it skillfully.

“I see us as primarily academic, but academic in a very unusual kind of way,” he explained in a Feb. 15, 1991, Hawai‘i Herald story. “It focuses on race and class—taking theories and trying to apply them to community problems, but treating the outside community with respect as peers and stressing that ES (Ethnic Studies) is there not just to teach the community, but to learn from it, as well.”

Franklin had “the experience, vision, connections, determination, and aloha to elevate the program into a department offering a B.A. degree,” McGregor said. Prior to that, students had to design their Ethnic Studies degree through Liberal Studies. He worked with former ES lab leaders and supporters in the Legislature and the university to increase the number of full-time tenure track positions so the program could evolve into a department.

He cultivated “a culture of mutual support and aloha among the faculty, lab leaders and students,” McGregor said, hosting gatherings at his home, finding resources so the faculty could travel to national conferences and involving faculty members in research grants. He also attracted funding to create opportunities for ES students to do internships at the Smithsonian Institution and to earn scholarships.

On a personal level, McGregor credited Franklin with helping her evolve from a graduate student into a full professor. He played a major role in her academic growth and development throughout the 45 years she knew him, she said. “He helped me navigate the UH system and the ins and outs of an academic career while also being an advocate for my community. He was a good friend who looked out for me and always had my back,” McGregor said.

By the time she earned her first sabbatical as a professor, Franklin had moved to the Smithsonian, where he invited her as the inaugural scholar-in-residence. One of her favorite Washington memories was celebrating hanami, the Japanese tradition of sipping sake and enjoying a picnic while viewing the cherry blossoms. “It was amazing, only we enjoyed the blooming of the cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C., on a lawn along the Potomac with his staff and my daughter.”

“Franklin was a keiki o ka ‘Āina—a child of the land,” McGregor said. “He always found a way to include a focus on Native Hawaiians and Hawai‘i. His spirit is indomitable.”

Ibrahim “Brahim” Aoude, professor emeritus of Ethnic Studies, reflected on the times he and Franklin would lean along the railing outside of Franklin’s “office” in the paint-faded portable buildings off of East-West Road, sharing light moments that made them laugh, despite Ethnic Studies’ challenges. “Franklin’s passing reminded me of the ephemeral nature of our existence as individuals. What remains are memories of shared experiences,” said Aoude, who taught classes in Hawai‘i’s political economy and the Middle East.

He said Franklin’s “organizational genius” was instrumental in galvanizing community support to further strengthen the program. Aoude himself served 13 years as Ethnic Studies’ director. He said Franklin’s accomplishments were the building blocks that elevated Ethnic Studies to a bachelor’s degree-granting department. He grew the program within UH and in the community while also nurturing and cultivating the program’s student scholars who became its supporters in the community after graduating.

Franklin worked with all segments of the community to eventually secure department status for Ethnic Studies in 1995. He believed the community was an integral part of Ethnic Studies and participated in community projects, believing they were partners who could learn from each other.

In addition to his ES responsibilities, Franklin also served on the University of Hawai‘i Press editorial board. In 1979, Gov. George Ariyoshi appointed him to the 1980 Okinawan Celebration Commission. Franklin was also appointed to the board of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and then served as its chair from 1986 to 1989.

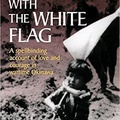

In 1985, the centennial anniversary of the arrival of the kanyaku imin, or contract immigrants, from Japan and the start of mass immigration to Hawai‘i, he co-authored A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawai‘i, 1885-1924, with Kazuko Sinoto of the Bishop Museum’s Hawai‘i Immigrant Heritage Preservation Center. Another of Franklin’s books, No Sword to Bury: Japanese Americans in Hawai‘i During World War II, detailed the story of the Japanese American UH ROTC cadets who were expelled from the Hawai‘i Territorial Guard because of their race. They went on to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers.

His most recent book, Voices from the Canefields: Folksongs from Japanese Immigrant Workers in Hawai‘i, published in 2013, highlighted the holehole bushi songs sung by sugar plantation workers as they labored in the fields. Franklin did extensive interviewing, documenting the stories of the people who had actually lived the history in the Ethnic Studies philosophy of “Our History, Our Way.”

To be continued ...

*This article was originally published in The Hawai‘i Herald on December 16, 2022.

© 2022 Karleen Chinen