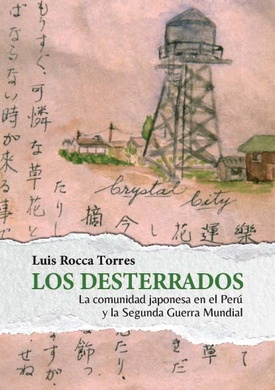

The book Los desterrados , which recently appeared in Lima, includes a list of the Japanese and Nikkei expelled from Peru and imprisoned in the Crystal City internment camp, in the United States.

The document, prepared by one of the prisoners in 1945, contains the names of almost a thousand people, including those of a great-uncle (my paternal grandfather's brother), his wife and some of his children.

Upon reading his name, Great Uncle Rensuke's memories cascaded. Or, to be more precise, the memories of my uncle Mitsuya talking about him, because I only knew him through his stories.

Mitsuya spoke about him as if he were a character in a novel, not just another family member. Sometimes I think he created a mythology around that guy he loved and admired. Maybe nostalgia enhanced the character, I don't know. In any case, what I remember from Mitsuya's descriptions is a proud man who responded to the greetings of people on the street from the material and symbolic height that being mounted on a gaited horse and his status as a prosperous merchant gave him. .

My uncle told me that Rensuke once took him to see a baseball game in an old stadium in the city of Callao, where they lived. They were in the stands when, suddenly, Rensuke, outraged by the referee's incompetence, came down to the field, interrupted the game and began to referee in place of the inept one. That's how bold he was.

Mitsuya told stories like this about Rensuke with enthusiasm and with his chest puffed out, putting as much emphasis on words as gestures.

He did not lose his spirit even when he told sad stories, like all those related to the Second World War. Rensuke was hidden so as not to be captured by the Peruvian authorities and deported to the United States, until he decided to turn himself in when he was told through his family that if he did so he could take his wife and children to the United States. So he did and set sail. to Texas with them.

I imagine that for Mitsuya, his uncle's departure was like losing a childhood hero.

In addition to activating family memories, reading the book Los desterrados made me think about the fate of the deportees after the end of the war. Rensuke was 55 years old when the prisoner list was made in Crystal City in 1945. At that age he had to return to a destroyed Okinawa and start from scratch.

In a magazine that was published to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Pacific Club, an institution created by Issei youth in the first post-war years (one of the most important in the history of the Peruvian Nikkei community), it was said that at the end of the war the older Issei were deeply demoralized. They had suffered looting, closure of institutions and schools, confiscation of businesses, etc.

“The old immigrants lost their entrepreneurial spirit with the moral blow of the Japanese defeat,” the magazine said. An Issei who was young when the war ended recalled: “At that time we were 30 years old and we could start over, but they (referring to the elders)… were physically and morally defeated.”

If this is how the older Issei felt in Peru, who despite all the abuses they had suffered had been saved from deportation and total ruin, I imagine that exiles like Rensuke must have felt ten, a hundred times worse.

They migrated to Peru fleeing poverty, but they were young and vigorous. In their new destination, thanks to their work, they managed to build a good life. Until the war broke out. Decades later, they returned to their country as poor as when they emigrated, aged and with a broken soul, and with the feeling that all the effort deployed in Peru was for nothing.

My uncle Mitsuya never told me what Rensuke's life was like in post-war Okinawa, but one of the testimonies in The Banished Ones brings me closer to him.

NO RICE OR SHOES

In the last decade of the last century, the book's author, sociologist Luis Rocca Torres, interviewed several survivors of the American camps. They were children then, and around half a century later, now in their sixties, they remembered their experiences of imprisonment.

One of the interviewees, Lidia Naeko from Tamashiro, was in Crystal City with her grandparents. When the war ended, he traveled to Japan with them. I was 8 years old. They settled in Okinawa, where food was a luxury. “We ate plants. When the sweet potato was gone, we ate the leaves. Sometimes we used petroleum oil for frying. When you are hungry, you eat everything. There was no rice or meat,” he recalled.

“We also ate wild herbs. After five years we just started eating meat,” he added.

Lidia brought the clothes and shoes she wore in Crystal City to Okinawa, but there was so much poverty in Japan that her shoes drew attention: “When I went out on the street to walk, the people who were without shoes looked at me a lot, so I I took off my shoes and started walking barefoot, like everyone else. Everything was walking in Okinawa, there was no mobility.”

The war claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of soldiers and civilians in Okinawa. Lidia recalled during Luis Rocca's interview that “there were many orphans and widows.”

To that Okinawa of barefoot poor people, without enough food and with broken families, Rensuke returned with part of his family (some of his children stayed in the United States).

Above I wrote that great-uncle had to “start from scratch” in his homeland, but I think that expression is not fair. Starting from scratch suggests a second chance, the possibility of reinventing oneself, but that was not the case for him or for people like him who were approaching old age and who had everything taken away from them. Life for them was simply survival.

Lidia’s grandfather (an immigrant named Seiji) said to his granddaughter shortly before he died: “Why do I always have bad luck? Misfortune always happens to me. When I was young I was in Okinawa and there was poverty and suffering. I went to Peru to improve and when I was doing well, the war came and we lost everything; Then they took us to the United States, locked up. Then Japan lost the war. When we returned to Okinawa, there was more poverty and we suffered.”

I'll never know, but I think Rensuke would subscribe to every word his countryman Seiji said.

I suspect that Mitsuya refused to tell the story of his uncle's life in post-war Okinawa because perhaps he thought there was no epic in mere subsistence, as well as to preserve his childhood memories, so as not to tarnish the image of the hero on horseback.

OTHER STORIES

Los desterrados also tells the odyssey of a Peruvian woman who traveled with her eight children to the United States to reunite with her Japanese husband, deported two years earlier.

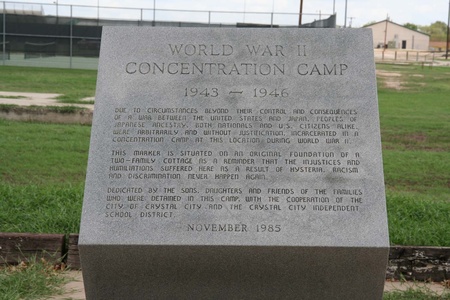

“They got off the bus (in Crystal City) and the first thing they saw were the wire fences, the posts, the watchtowers, the sentries and the mounted police. Without hesitation, she advanced toward the front door, grabbing her youngest children. Her eyes searched for her husband. He crossed the entrance door, stopped, looked around the facilities and finally spotted the silent Mantaro (Kague). Everyone ran towards him and hugged him. The most children clung to dad's legs; Everyone cried with deep emotion. 22 months had passed since the day of separation.”

Just as Micaela Castillo, Mantaro's wife, left Peru to share her spouse's confinement, Japanese immigrant Shuizake Aoyagi voluntarily moved to Crystal City to reunite with his wife and children, who had accompanied Mantaro's adoptive parents. her to the United States.

After recovering from the ravages caused to his mental health by the brutality of the local police (arrest and torture), Aoyagi only had a head for his family. The Exiles reproduces the dialogue that took place between Shuizake and some Japanese friends:

—Do you want to see your wife and children?

"Yes," he answered.

—But that means going to a concentration camp!

"It doesn't matter," he replied.

Finally, Aoyagi traveled to the United States, where he returned to see his wife and three children. Love was stronger than freedom.

The three stories reviewed are part of the book that, in addition to highlighting the human component of the deportations, contains valuable information, such as the sinister work carried out by the American agent John Emmerson in preparing the lists of Japanese immigrants who were to be expelled from Peru.

For readers unfamiliar with this dark episode in the history of Japanese immigration to Peru, Los desterrados is an important source of data. In addition to offering details about Emmerson's work, including his trips through the interior of the country to gather information, he describes the anti-Japanese climate that existed in Peru even before the war and the campaign promoted by those in power against the community of Japanese origin.

For readers familiar with the facts, the book gives faces and names to its protagonists, so as not to forget that behind the figures and data there are human beings.

© 2022 Enrique Higa Sakuda