In our previous section, we discussed Carlos Bulosan’s biography and his rise to success as an Asian American writer during the war years. While Bulsan wrote as a representative of Philippine Americans and centered his discussion on the experience of Pinoy workers, he showed a deep interest in other Asian American groups, particularly Japanese Americans.

At a time when tensions were high between Filipino and Japanese Americans due to the Pacific War, Bulosan expressed feelings of friendship, empathy and admiration for the Nisei. In return, several Japanese American writers, including Mary Oyama Mittwer, Hisaye Yamamoto, and Koji Ariyoshi, identified Bulosan as a kindred spirit, in the process foreshadowing the interethnic solidarity that would come with the Asian American movement.

Although Bulosan’s writings do not specifically express his feelings regarding Executive Order 9066, an FBI informant recounted a conversation he had with Bulosan during the author’s visit to the Writer’s Congress in October 1943, where he gave a speech discussing racial discrimination and the war effort. Bulosan told his interlocutor that the forced removal of Japanese Americans had robbed him of his own support system. Bulosan stated that with his Japanese American friends gone, he did not even know where he would be able to find a host to welcome him that night:

“In the past I have been friendly with the Japanese. In America they were a kind people and generous. They were not ashamed of my friendship and received me gladly. Today there are gone and in my Islands they are my enemies. But the white people here in California are no more my friends than before. I am confused to know why I fought and bled terribly and had such pain and almost died.”

Although Japanese and Chinese Americans appear only as minor characters in his works such as America is in the Heart, Bulosan’s portrayal of them emphasizes the shared struggles of Asian Americans facing discrimination on the prewar West Coast. Bulosan notes encounters with Japanese Americans on several occasions.

While Part 1 sketches the economic hardships facing Filipino farmers under American colonialism, Parts 2 and 3 depict the shared struggles of various Asian American groups in the enclaves of various West Coast cities. In the towns of Pismo Beach and San Luis Obispo, the narrator and his friends frequent Japanese-run hotels and gambling houses. The narrator’s friend, José, meets a Japanese woman, Chiye, near Pismo Beach, and has a brief romance with her until discovering she needs to go back to her husband. In the town of Lompoc, the narrator witnesses the mugging of a Japanese man.

In Part 4, as the narrator begins his intellectual journey, he searches for a writer like himself for inspiration. After digging through the Los Angeles Public Library, he discovers Yone Noguchi: “a Japanese houseboy in the home of Joaquin Miller, the poet… here at last was an ideal.” (In fact, while Yone Noguchi had previously worked as a domestic; he was invited to live as a guest in Miller’s house, and while there made multiple connections with San Francisco bohemians—most notably Charles Warren Stoddard, who became his champion and his lover).

Bulosan’s work had an immediate impact on contemporary Japanese Americans. Even in the prewar years, Bulosan’s name and his work seem to have been known to Larry Tajiri, the editor of Nichi Bei Shinbun and an arbiter of taste among Nisei. In the 1941 New Year’s issue of Nichi Bei, Tajiri praised the circle of California Filipino writers for their powerful writing, though he did not single out Bulosan:

“The Filipinos have Jose Villa who wrote of loneliness in an alien land, and who published a magazine, Clay. And there was a vivid piece by a young Filipino in a recent issue of New Republic which told of humiliation at the hands of police officers in a western city—just because he happened to be a Filipino.”

After the war, Nisei writers lavished particular praise on Bulosan. In the March 16, 1946 issue of the Pacific Citizen, Larry Tajiri pointed to Bulosan’s America is in the Heart as a must-read book that combatted racial stereotypes of Filipino Americans. Tajiri also described Filipino Americans as the current recipient of prejudice from white nativists that had been previously directed towards Chinese and Japanese Americans.

In May 1946, writer Mary Oyama reviewed America is in the Heart for the Rafu Shimpo. Oyama echoed Time magazine’s praise of the book, and recalled to readers her own meeting with Bulosan at the Writer’s Congress. Oyama described Bulosan as “a quiet but intense, and serious-minded sort of fellow, modest and very sincere,” and surmised from his life experiences that “the vexing problems which beset Filipino Americans [are]many more difficult than that which harass the Nisei.” Oyama concluded her review by encouraging Nisei readers to “pause, read, and get to know a real Filipino. He is very different from the stereotype.” Likewise, Charles Kikuchi mentioned in his diary that he was reading “America is in the Heart” during a journey through the South in 1946.

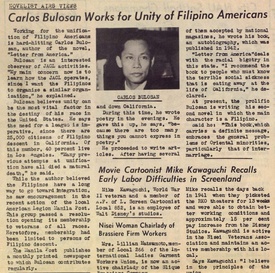

In October 1947, the Los Angeles Vanguard, the newsletter for the Los Angeles chapter of the JACL, profiled Bulosan and his attempts to unify Filipino American communities. “Many previous attempts at unification have all died a natural death.” The Vanguard described Bulosan as “an interested observer” of the JACL. “My main concern now is to learn how the JACL operates, since I want the Filipinos to organize a similar organization.”

The article also noted Bulosan’s literary efforts, explaining that he started by writing poetry in the evenings after the workday, only to discover “There are too many things you cannot express in poetry.” It mentioned that Bulosan was at work on a second novel. (In 1995, Temple University Press posthumously published this novel under the title The Cry and the Dedication. Set during the Huk Rebellion in postwar Philippines, the novel highlighted the ongoing class struggles of Filipino workers.).

Outside the Japanese American community, several literary critics drew parallels between Bulosan and Japanese American writers. In William G. Roger’s review of Ben Kuroki’s ghostwritten 1946 memoir Boy From Nebraska for his syndicated column “Literary Guidepost,” Rogers compared Kuroki’s vision of America to Bulosan’s views. Rogers concludes that Kuroki, “like Bulosan,” is convinced that “most Americans are on his side.”

In 1950, Ward Moore, literary critic and journalist for the San Francisco Chronicle, interviewed Bulosan alongside Nisei writer Hisaye Yamamoto, as part of an article exploring Asian American writers. In his article, Moore contrasted the styles of Yamamoto and Bulosan, describing Yamamoto as “an intellectual” and Bulosan as “an artist”:

“Except that both are serious writers, the two have little in common. Miss Yamamoto, like most contributors to ‘little’ magazines, is a classicist, occupied with form and texture, extremely conscious in her approach; Mr. Bulosan is a romantic who is so moved by the force of emotion that he carries his effects to his readers by sheer passion. His literary discipline is fundamental, evidently established in the very process of learning to put words together efficiently; Miss Yamamoto’s is obviously imposed and clearly requires constant enforcement. She experiments, even at the risk of stumbling and floundering. Mr. Bulosan’s footing is surer, for his path is narrower; she is an intellectual, he is an artist.”

Following Bulosan’s death in 1956, his writings went unnoticed until their resurrection in 1973 amidst the Asian American movement. Reprinted by the University of Washington Press with an updated introduction by Carey McWilliams, the new edition was among the first Asian American works published by University of Washington.

Tetsuden Kashima later argued that UW’s decision to do the reprint - inspired in part by their eagerness to republish John Okada’s novel No-No Boy - “showed that the publisher was willing to listen to Asian American voices.” The new edition inspired diverse writers and scholars interested in the plight of Asian Americans. As Lane Ryo Hirabayashi and Marilyn Alquizola described in their introduction to the 2014 edition:

“America is in the Heart still stands today as both an indictment of twentieth-century American imperialist designs overseas and a testament condemning a pre-World War II domestic regime of racialized class warfare.”

The Asian American movement inspired wider community recognition of Bulosan as an icon of Asian American literature. In 1973, labor activist Koji Ariyoshi referenced Bulosan’s America Is In the Heart (mistitled as “America is a Dream”) in his article “Nisei in Hawaii” for Japan Quarterly. Ariyoshi compared Bulosan’s life of suffering to that of the Nisei in the U.S., and argued that both saw America “as a dream” despite facing racial discrimination. In May 1984, the Pacific Citizen reprinted an article from the International Examiner on the efforts of local Asian American and union activists to collect funds in order to provide a proper tombstone for Bulosan’s grave.

Bulosan’s connections with Japanese Americans further demonstrate his expression of an Asian American consciousness, even before its popular articulation in the 1970s. His early writings indicate Bulosan’s own desire to build coalitions with other Asian American groups and their writers. This also contrasts with the popular narrative of hatred between Filipino and Japanese Americans, which reached a fever pitch during the Pacific War.

© 2022 Jonathan van Harmelen; Greg Robinson