In 2018, five Sansei women artists traveled to Manzanar’s annual pilgrimage in order to honor their family histories of wartime incarceration. Each of them had worked with this history in some form in their wide-ranging art careers, but this journey was special. In order to chronicle their experiences, they created a documentary, Sansei Granddaughters’ Journey.

Now the five artists (Ellen Bepp, Shari Arai DeBoer, Reiko Fujii, Kathy Fujii-Oka, and NaOmi Judy Shintani) are bringing their art, their documentary, and their expertise to another site of Japanese American wartime incarceration: Tanforan, a former temporary detention center in San Bruno, California. The accompanying exhibit Sansei Granddaughter's Journey: From Remembrance to Resistance, which opened in July 2022 includes multiple programs to engage audiences, at AZ Galley in San Bruno.

The artists will be giving talks, teaching workshops, showing their artwork, and partnering with organizations like 50 Objects and Topaz Stories to provide additional layers of context for the exhibit. The artwork includes mixed-media pieces, installations, paintings, prints, and video. The timing of the exhibit will overlap in part with the dedication of the new Tanforan Memorial and the Tanforan Incarceration 1942 exhibit at the San Bruno Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) station.

Like many descendants of Japanese American wartime incarcerees, I am still working through what it means to inherit this painful and powerful history. As a Sansei writer, I was honored to work with the Sansei Granddaughters’ Journey artists group for their exhibit, writing two commissioned panels. I created a brief timeline overview of camp history, as well as another panel featuring the artwork and family story of Sansei artist Lucien Kubo. Because Lucien is a direct descendant of Tanforan inmates, her family story is an important one that is now shared at the site. With her permission and that of the Sansei Granddaughters, I have included a longer version of her family story here.

* * * * *

“I Look Back Into History”—Lucien Kubo

For Sansei artist Lucien Kubo, the echoes of her family’s wartime incarceration at Tanforan resonate strongly across decades into the present. And like many Japanese American descendants of camp survivors, she is still grappling with the silences and the strong voices which emerge from her family history.

Kubo’s immigrant grandparents, Shunzo and Miyo Suzuki, operated a dry-cleaning and laundry business at 881 Sutter Street in San Francisco. They had lived close to 20 years at this address and had three teenage children (William, Mary, and Florence) when World War II broke out.On February 19, 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to forcibly remove more than 110,000 Nikkei from the West Coast. Two days later, Shunzo was rounded up by FBI agents as a known community leader and businessman, and sent to the Silver Avenue Immigration Office in South San Francisco.

When Shunzo’s family tried to bring him some personal necessities just two days later, they were told that he had already been put on a train to a detention facility in Bismarck, North Dakota. Just weeks later, Mrs. Suzuki and her children had to follow the Civilian Exclusion Orders for forced evacuation. They had to dispose of their business and its assets, most of it at a loss. They reduced the majority of their personal belongings to several duffel bags that they could carry and rode buses to the temporary detention facility at Tanforan in San Bruno.

The living conditions were harsh; the youngest Suzuki daughter (and Lucien’s mother) Florence described them as “cold, miserable, and smelly.” Prisoners slept on straw mattresses and frequently waited in lines for the mess halls, the communal latrines, and the laundry. Barbed wire and guard towers surrounded the facility, with all visitors being searched for contraband.

From Tanforan, and with the assistance of her children, Miyo Suzuki wrote a several-page typewritten appeal to Francis Biddle, the United States District Attorney. Citing her husband’s broad record of community service and their children’s strong academic marks in citizenship, she pleaded with Biddle to ascertain the truth about her husband’s loyalty. “Before his arrest,” she wrote, “he was planning to help sell United States Defense Bonds among Japanese residents.”

Just before the Suzukis left for Topaz, another concentration camp in Utah, Shunzo reunited with his family. They found out that on the train to North Dakota, Shunzo had suffered an injury during the long ride due to a sudden stop—but received no medical attention. The anger and grief at this unexpected separation and medical neglect remained for decades. “What a traumatic shock it was for all of us,” wrote Lucien’s mother, Florence, in her testimony for the redress campaign in the 1980s.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and young Lucien was watching the 1960s unfold on television, connecting the Civil Rights and antiwar movements with her family story. Attending San Francisco State University in the 1970s gave her firsthand activist experience with Japanese American community struggles against gentrification and displacement in San Francisco ‘s Japantown and then Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. “I was informed and given direction from the Civil Rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War,” she reflected later in an artist statement. Understanding the interconnections between histories and movements, she continued her activism with the women’s, LGBTQ, environmental justice, labor, and immigrant rights movements.

Reading Miné Okubo’s graphic memoir Citizen 13660 in college gave Lucien a deeper understanding of what her family had endured at Tanforan and then in Topaz. Finding her mother’s powerful written testimony for the redress campaign and reading her grandmother’s wartime petition to the government also helped her find strength in the voices of her family's past.

After Lucien’s children had grown, she began to make art as another language and form for her activism. Using documents and old photos in her mixed-media collages, she has exhibited in museums, co-curated political exhibits, and participated in solo and historical exhibitions throughout northern and central California, such as the Hidden Histories of San Jose Japantown.

With newer waves of anti-Asian racism and rhetoric, Lucien continues her activism with Indivisible Santa Cruz County and San Jose Nikkei resisters helping others to see parallels in different injustices across time.

“I look back into history,” she says.

* * * * *

The art exhibit Sansei Granddaughters’ Journey will be on display through Saturday, Sept. 3 at AZ Gallery in San Bruno, CA. For a full calendar of exhibit-related events, see here >>

More of the Sansei Granddaughters’s artwork appears below:

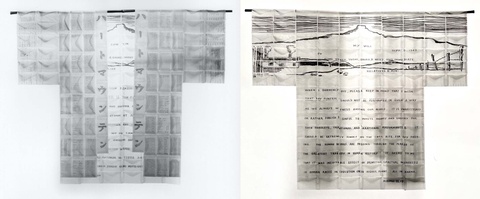

Heart Mountain Happi by Ellen Bepp

The happi form that is constructed of small glassine envelopes honors Ellen Bepp's paternal grandfather Kiroku Bepp with images in each envelope referring to memories of a tragic period of WWII incarceration. On the back of the happi form is a drawing of Heart Mountain, the barracks, and his last will written while he was a prisoner.

The Golden Crane by Kathy Fujii-Oka

She captures her grandfather’s facial expression—the devastation and pain, the downward gaze of loss, and the loneliness without his wife and children, as he gardened at Gila River Concentration Camp. In his hand, he sows the seeds of hope as the golden crane swoops in to soothe his spirit, symbolizing hope, peace, compassion, and healing.

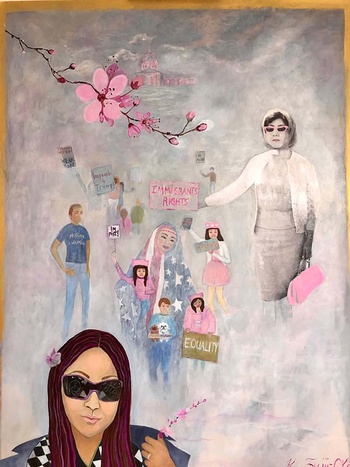

My Mother, My Daughter by Kathy Fujii-Oka

Her mother was an immigrant from Japan and with Fujii-Oka in spirit. As an artist, she links the ancestry of her mother through herself, to her daughter and grandchildren, whose generation will continue to carry the torch of empowerment for women and people of color into the next generations. After attending a S.F. Bay Area Women’s March, Fujii-Oka wanted to pay tribute to the women in her family.

© 2022 Tamiko Nimura