Nisei Collegians

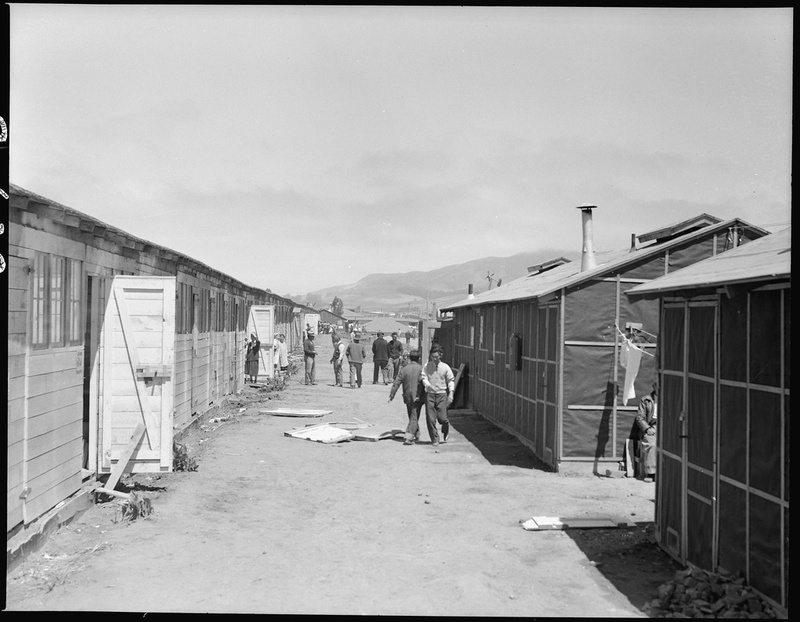

Given its urban population and proximity to Bay Area colleges, it is likely that there was a higher concentration of college students at Tanforan than at most other “assembly centers.” Though most were not immediately able to continue their education, there were a few who were able to leave Tanforan to attend college—and thus avoid going to a WRA concentration camp—often with the assistance of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, which formed at the end of May 1942.

Among them were former UC Berkeley students Masako Amemiya and Lillian Ota. Largely through her own initiative, Ota was able to secure a scholarship to Wellesley and later became something of a poster girl for the possibilities of Nisei collegians for the council and WRA.

Amemiya’s journey was a bit bumpier. Also a Berkeley student when incarcerated, she gained admission to Elmhurst College in Illinois with the aid of the NJASRC. But just as she was preparing to board the train east, her trip was canceled due to adverse reaction from the local community. Fortunately, an alternative was found in fairly short order, and she ended up leaving for Cornell College in Iowa, where she reported a positive experience.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study

Given that the Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) was based at the University of California at Berkeley, it should not be surprising that several student fieldworkers—along with some who were not students—were at Tanforan, documenting various aspects of the camp. They included Doris Hayashi, Fred Hoshiyama, Ben Iijima, Charles Kikuchi, Tamotsu Shibutani, and Earle Yusa among others. (You can learn more about each from the linked Densho Encyclopedia articles.)

Though the JERS project was controversial due to the ethical dilemma of conducting research in concentration camps and lack of consent from subjects, there is no question that the various reports and diaries produced by these researchers have contributed to Tanforan being perhaps the best documented of any of the “assembly centers.” The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley has digitized and put online JERS records starting in 2011. We draw from their observations in many places in this article.

Poets, Activists, Anthropologists, and Other Prominent Visitors

As with other “assembly centers,” dozens of locals visited Tanforan to see old neighbors and communicate with former business partners. Yet because of its proximity to the Bay Area, several noteworthy individuals visited Tanforan to witness the camp firsthand, including Dorothea Lange, who photographed the camp during its opening days, and anthropologist Margaret Mead. The head of the aforementioned JERS Project, Sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, visited Tanforan on several occasions to meet with her staffers and to collect data as part of the project.

During one of Thomas’s visits with her Japanese American informants, Army officials stepped in, confiscating Thomas’s notes and interrogating her and her Nikkei informants. After this, Thomas and her associates needed written permission by the Wartime Civil Control Administration, which oversaw the forced removal and managed the “assembly centers,” in order to enter the camp. Other blacklisted visitors included actor, activist, and later Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas, who at the time was a member of the Democratic National Committee and an advocate for gender and racial equality. Likewise, racial profiling was commonplace, as the guards paid additional attention to African American visitors.

Perhaps one of the more fascinating visitors at Tanforan was poet Kenneth Rexroth. Later known as the “Father of the Beats,” Rexroth became a leading figure in the San Francisco literary scene, and is often regarded as helping San Francisco develop a literary tradition. A poet with strong leftist convictions, Rexroth and his wife made several trips to Tanforan to support Japanese Americans. Rexroth collected books for the Tanforan library and his wife, Marie Kaas, volunteered as a nurse at the camp’s infirmary. Rexroth also befriended San Francisco activist and YMCA secretary Lincoln Seiichi Kanai. Known for his court case against the West Coast exclusion zone, Kanai engaged in a tour of the Midwest on behalf of Japanese American students with help from Rexroth before his arrest in July 1942.

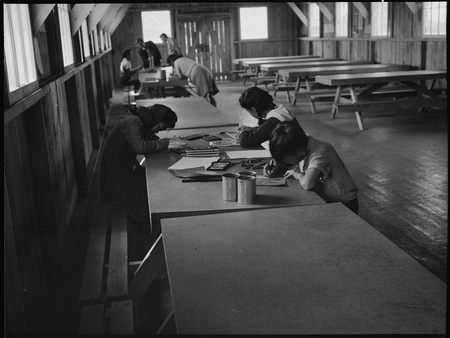

Art and Music Studios

Because of its proximity to the universities of the Bay Area, Tanforan housed an art and music school staffed with professors and students. As previously mentioned in the Densho Catalyst, the Tanforan Art School was run by famed painter Chiura Obata, and notable faculty included artists such as Miné Okubo and Hisako Hibi. Surprisingly, the Tanforan Art school offered more teachers and classes than its later iteration, the Topaz Art School, as many of the instructors left Topaz following the leave clearance program.

Yet less-known is the Tanforan music school and studio. The school was housed in the Tanforan Tavern, a former recreation building for the employees of the Tanforan racetrack. The school was run by Frank Iwanaga, and offered classes in harmony and music history, along with private lessons in piano and violin. By the start of the school, 75 people registered for piano lessons and 25 registered for violin lessons. The school’s first concert was held on June 13, 1942, and featured a variety of piano, violin, and vocal solos featuring the works of Mendelssohn, Chopin, and Debussy. By the time Tanforan closed in September 1942, over 500 students had enrolled at some point in the Tanforan music school.

The Setting for Japanese American Literary Classics

Tanforan figures prominently in several camp memoirs, such as Yoshiko Uchida’s Journey to Topaz and Miné Okubo’s Citizen 13660. Yet there are also works of fiction that are set at Tanforan. Perhaps the most famous example is Toshio Mori’s short story “The Man with the Bulging Pockets.”

Originally published in the December 23, 1944 issue of the Pacific Citizen, “The Man with the Bulging Pockets” centers on an elderly Issei man who wanders the camp distributing candy to young children. Gaining a following among the youth at Tanforan for his generosity, the Old Man is nicknamed “Grandpa.” One day, an older Issei bachelor is found also distributing candy, and tells the children to not accept Grandpa’s candy because it is dangerous. When the children reveal the old man’s jealousy towards Grandpa’s popularity, Grandpa responds to the children with grace: “I am not mad because I have many nice friends. He needs nice little friends too, don’t you think?” Although the children listen, Grandpa remains concerned about the divide between him and the old man. Mori concludes the story with an insightful last line: “They should inspire and sing in the oneness of hope, but no. They were partisans, and the split in their circle was the enigma and blot of all mankind.”

Mori later republished the story in his 1979 volume The Chauvinist and Other Stories.

Segregated Restrooms for “Colored Gents”

Finally, an observation by the ever-observant Charles Kikuchi:

“I ran across an interesting restroom today. Down by the stables there is an old restroom which says ‘Gents’ on one side and ‘Colored Gents’ on the other! I suppose it was for the use of the stable-boys. To think such a thing is possible in California is surprising. I guess class lines and the eternal striving for status and prestige exists wherever you go, and we are still in need of a great deal of enlightenment.”

That last line remains as true today as it was then.

*This article was ooriginally published in the “Densho Catalyst” on August 25, 2022.

© 2022 Brian Niiya and Jonathan van Harmelen / Densho