Brazil is a large South American country located on the other side of the world from Japan. There are 1.9 million Japanese people living here, making up the world's largest Japanese community. When the number of immigrants from any country increases, people naturally gather together and form communities similar to those in their home countries, giving birth to a small community of their home country in a foreign country.

Stores and streetscapes similar to those in the home country are created, but they are not the same. The climate, culture, and social system are different, so what is born is an adaptation of things from the home country, and it can be said to be "home country style."

As time passes, the generations change, the descendants of immigrants gradually become part of the country, and the culture cultivated by the first generation is further adapted, eventually resulting in a new culture that is a fusion of two or more elements. The community also changes.

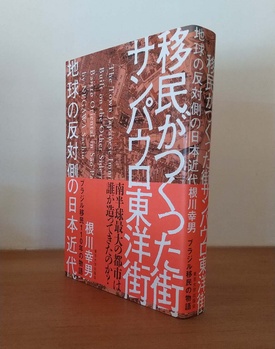

The book "São Paulo Oriental Town, a Town Built by Immigrants: Modern Japan on the Other Side of the World" (by Negawa Yukio, published by University of Tokyo Press in 2020) teaches us about these changes in immigrant society through the lens of Japanese (and Japanese-Brazilian) society in Brazil.

An invitation to a new culture

The author lived in São Paulo for four years from 1996, and compiled his master's thesis, "The Formation and Transformation of São Paulo's Oriental Town: One Aspect of Asian Immigrants in the City of São Paulo," as a summary of his research there. Using this as a basis, this book "describes the formation, development, and transformation of São Paulo's Oriental Town, which was called the world's largest Japanese town, mainly based on written sources and people's memories."

The author's words, "Through this short book, I would like to invite readers on a journey to another Japan on the other side of the globe, to another Japanese person who lived in the modern era between Japan and Brazil," convey his passion and interest in the Japanese and immigrant community in São Paulo.

I believe that researchers involved in immigration studies share these feelings, that is, sympathy and interest for people who lived in foreign lands between Japan and other countries during a tumultuous period marked by war.

History of the development of Japantown

When you think about it, it is strange that another small "Japan" was born in the place farthest from Japan. Such Japantowns have sprung up not only in São Paulo but all over the world. Before moving on to the main topic of "Japantown in São Paulo," this book introduces Japantowns that have existed in Little Tokyo in Los Angeles, Davao in the Philippines, and Shanghai. Other examples include Vladivostok in Russia, which I mentioned in a previous column.

Below, let's trace the history of Japanese people in São Paulo, Brazil, following the example of this book.

The population of the city of São Paulo was only 65,000 in 1872. This rapid increase was due to an influx of immigrants. The background to this was the growth of the coffee industry in Brazil, the center of which was the São Paulo region. Coffee plantations required a large amount of labor, and initially relied on slaves, but after the Emancipation Edict was issued, European immigrants were brought in to supplement this.

Looking at the number of immigrants to Brazil by country between 1819 and 1947, Italy had the most with approximately 1.51 million people, followed by Portugal with 1.46 million, Spain with approximately 600,000, Germany with approximately 250,000, and Japan in fifth place with approximately 190,000 people.

In Japan, overseas emigration began with the Meiji Restoration (1867), while in Brazil, a new government was born in 1889 as a result of the Republican Revolution. After diplomatic relations with Japan were established in 1895, the São Paulo state government decided to grant subsidies to Japanese immigrants, just as it did to European immigrants, in 1900. As a result, the first Japanese immigrants to Brazil left Kobe Port aboard the Kasato Maru in 1908, arriving in Santos, an outer port of São Paulo, after a 51-day voyage.

Most of the Japanese immigrants were agricultural immigrants, but some of them went to São Paulo and started self-employed jobs, and eventually those who left farming also came to the city. Just like in America, in response to the demand for Japanese food, businesses selling rice, miso, and soy sauce began, and when restaurants opened, Japanese people gathered and various demands were naturally created. In this way, Japanese towns gradually developed.

The first area to emerge was the "Conde Neighborhood," centered around Conde de Sarzedas Street, which was formed in the 1910s. As the city continued to develop, the number of Japanese people living in urban areas of São Paulo continued to increase, reaching 600 families and 3,000 people in 1933. This was just 15 years after the Kasato Maru immigration.

Furthermore, as the Japanese population increased, the area developed into a place where people of Japanese descent could live comfortably, with stores, banks, inns, schools, and other amenities. However, this development came to a halt with the war. Brazil was on the side of the Allies in World War II, and Japan was an enemy country, so the Japanese community in Brazil was persecuted.

Japanese residents of the Conde area were ordered to leave for security reasons. They were also forbidden to speak Japanese in public places. After the war ended, these restrictions on Japanese people were gradually relaxed. However, another problem arose in the Japanese community. This was the conflict between the "winners" - those who believed in Japan's victory - and the "makes" - those who accepted defeat.

In the 1950s, as the fighting calmed down, Japanese people began to gather again in the Liberdade district, especially Galvão Bueno Street, in place of the Conde district, which had been evicted. Then, in 1953, postwar immigration from Japan began again, leading to the formation of a new Japanese town called Oriental Town in the 1970s.

The first factor behind this was the opening of Cine Niterói, the first urban entertainment complex for Japanese Brazilians, in 1953. Other factors that could be considered were the founding of the Brazilian Japanese Cultural and Church Center (1964), the opening of the Liberdade subway station (1975), and the expansion of Japanese companies into São Paulo (1970s and 1980s).

As the area developed, Oriental Town, as its name suggests, attracted not only Japanese immigrants, but also Korean and Taiwanese immigrants.

How will Oriental Town change?

Taking this history into account, in the second half of the book the author examines how Japanese culture has been expressed by the Japanese community in modern Brazilian society, and whether it will be reintegrated into Brazilian culture, through events such as the Tanabata Festival and the Oriental Festival.

In the 310th issue of Japanese Folklore Studies published in May of this year, author Negawa wrote an article titled “Crossing Borders Urban Festivals – From the Space-Time of the Oriental Town of São Paulo, Brazil,” in which he examines the ethnic festivals in the Oriental Town, including the transformation of the town since the COVID-19 pandemic.

How is Japanese culture adapted, disseminated, and accepted on the other side of the globe from Japan? I have heard that some traditions remain in the host country more than in the home country, but at the same time, there may be ways of development that do not exist in the home country. This book's examination of the fascinating Japanese culture in Brazil, which is similar yet different, is just as interesting as the Japanese culture in Brazil.

© 2022 Ryusuke Kawai