In a previous article I co-wrote with historian Greg Robinson, I highlighted the life work of Maryknoll Brother Theophane Walsh. Like a number of Maryknoll priests and nuns active in Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo community, Brother Theophane spent most of his life working with the Japanese American community, helping to organize Boy Scout Troop 145 and, during the war, establishing a Chicago Nisei Youth Hostel for families resettling from camp. Like Brother Theophane, the work of Father Hugh Lavery is also worth remembering, both as a supporter of the Little Tokyo community during the war years and as one of the architects of Maryknoll’s presence in Los Angeles. Like Maryknoll itself, the story of Little Tokyo in many ways cannot be told without mentioning Father Lavery’s contributions.

Born in Bridgeport, Connecticut on April 12, 1895, Hugh Lavery was the oldest son of Irish immigrants James and Mary Lavery. After attending Lincoln High School in Bridgeport, Lavery enrolled at Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts. After briefly working as a clerk for the Remington Arms Company in Bridgeport, Lavery decided to follow the calling of the priesthood. Little is known, however, as to why he decided to join the Maryknoll order. Following years of training, Hugh Lavery was ordained as a Maryknoll priest on June 15, 1924. From 1924 to 1927, Father Hugh Lavery served as a professor at the Maryknoll Preparatory Seminary in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

In 1927, Father Hugh Lavery moved from Pennsylvania to Los Angeles to take charge of the Maryknoll School in Little Tokyo. There he advised the Boy Scout troops, led classes, and delivered sermons at the Maryknoll Mission. In October 1928, Father Lavery briefly left the school in to take charge of Mission San Juan Capistrano. Although the old Spanish was more known as a relic of Spanish California and a film location for Hollywood Westerns, the mission was occupied by Father Lavery in order to construct a school, hospital, and orphanage for Japanese American children.

Three months later, in January 1929, Father Lavery returned to the Maryknoll School in Los Angeles. During his tenure as head of the Maryknoll Mission and School, Father Lavery oversaw the expansion of the school and the implementation of a bus program to help transport students to and from the school. The bus program, which was directed by Brother Theophane Walsh, helped establish the Maryknoll school as one of the more accessible schools for Japanese Americans in the Los Angeles area. Perhaps the most impressive feat of Father Lavery acknowledged by the Japanese American community was his ability to master the Japanese language by working with the Issei, or first-generation immigrants.

Although Father Lavery would spend most of his career in Los Angeles, much of his prewar career was spent travelling between various missions. Starting in 1930, Father Lavery made a number of trips to East Asia. Although health issues prevented him from remaining overseas for most of his career, Lavery conducted numerous missions in Japan and Korea – then under Japanese control – between 1931 to 1936. Joining Father Lavery was Father John Swift, a Maryknoll Father that later worked at Rohwer, Jerome, and Granada concentration camps during World War II.

Upon his return to the U.S. in 1932 after a two-year mission, Father Lavery went to Seattle to assume control of the Seattle Mission. During his time in Seattle, Father Lavery advocated for Japanese language courses to be accepted for high school credit among Seattle schools. In response to a letter written by Lavery that was detailed in the Rafu Shimpo, the Superintendent of Seattle schools refused Lavery’s request to accept Japanese language classes as creditable to high school transcripts.

In November, 1935, Father Lavery returned to Los Angeles from Seattle to again assume control of Maryknoll Mission. In his place, Father Leopold Tibesar assumed control of the Seattle mission (for more information, see my previous Discover Nikkei article). In the years from 1935 until 1942, Father Lavery served the Japanese American community both as a spiritual leader and community organizer. In addition to his own role as a priest, Father Lavery organized community events. In 1936, Fathers Lavery and Caffrey organized a well-publicized meeting between child star Shirley Temple and Maryknoll students to help promote the school. In 1941, Lavery opened up the Maryknoll Mission for a Veteran’s Day party for 200 Nisei soldiers stationed at Camp San Luis Obispo.

The months immediately following Pearl Harbor drastically troubled Father Hugh Lavery. In the wake of mass arrests of Issei community leaders conducted by the FBI, Father Lavery went with Father Clement Boesflug to Fort Missoula, Montana, to testify at enemy alien hearings to the loyalty of Los Angeles’s Issei leaders. Spending thirty minutes speaking with the internees individually, Father Lavery reported to the Rafu Shimpo that most had a good chance for release and that he submitted a report on his work to the Justice Department. A letter in response to his report was written by James Rowe, Assistant to the Attorney General, and republished in the Rafu Shimpo on February 23, 1942.

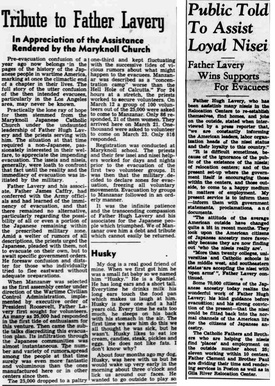

Between February and March 1942, the Japanese American leaders like Togo Tanaka and Father Lavery regularly held meetings at the Maryknoll auditorium to discuss resettlement plans. As news of the incarceration began to trickle in through government channels, Father Lavery counseled the Japanese American community in the Rafu Shimpo to not sell their belongings and prepare for removal from their homes. Likewise, Father Lavery helped organize plans for a community convoy to Manzanar leaving the Maryknoll Mission. As the incarceration process unfolded, Father Lavery received disturbing news from Colonel Karl Bendetsen, the head of the Wartime Civil Control Administration. When Lavery asked Bendetsen about the status of mixed-race orphans in relation to forced removal, Bendetsen ordered Lavery that “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them they must all go to camp.”

The sting of Bendetsen’s words troubled Father Lavery for the rest of his life.

Throughout the war years, Father Hugh Lavery spent his time travelling between the ten WRA concentration camps. Although Lavery regularly visited with his parish at Manzanar, he frequented the various camps to provide sacraments to other Catholic communities in need of a priest. He also frequently visited Los Angeles to check on the stored property of Japanese Americans stored at the Maryknoll Mission. Nisei Catholics like Pacific Citizen editor Harry Honda remembered Lavery’s travels as part of his “10,000 mile parish.”

During his visits, Father Lavery baptized the first baby at Poston camp in September 1942, officiated weddings, and delivered films to the various camp communities. He also arranged for Nisei students to enroll at various Catholic universities outside the West Coast, with Lavery releasing a call for forty Nisei women to enroll at Quincy College in Quincy, Illinois. In March 1943, the Manzanar Free Press honored Father Lavery with a tribute to his work. During his visit to Tule Lake in February 1944, Father Lavery was photographed performing mass by LIFE Magazine photographer and war correspondent Carl Myden for his article on Tule Lake.

Shortly before the closure of Manzanar concentration camp in November 1945, Father Lavery officially returned to Los Angeles to help Japanese Americans resettling in the city. In the New Year’s Day 1946 issue of the Rafu Shimpo, Father Lavery shared a saddened reflection about life after camp:

“The evacuees have returned. There was no public acclaim of a welcome; rather of studied silence built up in anticipation, a bad sentiment about a good people, and we were led to believe by false teachers and prejudiced leaders that the exiles, being guilty of crime and criminal tendencies, were deserving of no homecoming. Alas, the strangeness of truth! Tried in the courts, there were no charges of guilt; questioned by the bureau of investigation, no charges were found. So wisdom is justified in her children.”

Although Father Lavery returned to his daily duties at the Maryknoll Mission in Los Angeles, he spoke out on multiple occasions against the unfair treatment of Japanese Americans. When President Harry Truman announced that he would appoint Karl Bendetsen to Assistant Secretary of the Army in 1949, Lavery penned a letter to the President protesting the nomination. Calling Bendetsen “a little Hitler,” Lavery cited his demand to incarcerate all orphans based on the blood rule, and stated “just as with Hitler, so with him. It was a question of blood.” The letter was quoted by the Pittsburgh Courier and the Washington Post, and was later featured in Larry Tajiri’s column in the Pacific Citizen. A similar protest was mounted by Secretary Roy Wilkins of the NAACP, arguing that his nomination would hinder the “elimination of racial discrimination in the Armed Forces” because of his wartime treatment of Japanese Americans. Despite these protests, the Senate unanimously confirmed Bendetsen by roll call in February 1950.

After decades of service to the Maryknoll Mission of Los Angeles, Father Hugh Lavery announced his departure from Los Angeles in November 1956. Following a farewell party organized by the Maryknoll School on November 10th, Father Lavery left in December 1956 for New Orleans, where he served as a priest at the Maryknoll Promotion House.

Despite Father Lavery’s absence from Los Angeles, the Japanese American newspapers like the Rafu Shimpo and the Shin Nichibei published updates on Father Lavery’s life. Following a stroke in November 1960, Father Lavery retired from the Maryknoll order and returned to Bridgeport, Connecticut. On April 29, 1966, the government of Japan bestowed upon Father Lavery the Order of the Rising Sun, Fifth Class, for his wartime support of the Japanese American community. After four years of retirement, Father Hugh Lavery died on April 30, 1970. Shorlty after, the Rafu Shimpo eulogized Lavery’s life and his dedication to the Japanese American community.

© 2021 Jonathan van Harmelen