June Baldwin and her son Leon reflect on their mother and grandmother, Hiroko Kadowaki, who migrated to New Zealand in 1956 after marrying a New Zealand soldier she’d met in Hiroshima.

* * * * *

JUNE (Nisei):

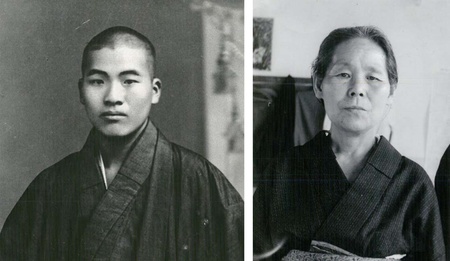

My mother, Hiroko, grew up on the small island of Daikonshima in the middle of a lake in Matsue City, Shimane prefecture, on the north-west coast of Japan. She was the third of four children. Her parents farmed their land. Mum often talked about their fruit orchard and soy beans, and how they made their own soy sauce and silk.

Mum dreamed of living abroad and becoming a doctor. Unfortunately, her family couldn’t financially support her, so she trained as a nurse from the age of 14 during WW2. When the atomic bomb hit Hiroshima, she was sent to assist the wounded. She was not yet 16.

She continued her nursing career at the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. That’s where she met my father, James. He’d been injured as a gunner in the New Zealand Kayforce during the Korean War. They married when my mother was 26 and my father 29. Mum’s family were not supportive at first, but before she left Japan her father told her she would always be welcomed back.

My mother arrived in New Zealand in 1956 and settled in Auckland with my father. Dad’s family were welcoming, but it was a huge culture shock. She was unable to speak English, disliked the food, had to convert to Catholicism, and was unaware till meeting my father’s family that he was not Caucasian! (His mother was a Maori from Mangaia in the Cook Islands.)

Within a short time, my mother adopted the name Maria. I was born in 1957, then my brother, Arthur, in 1958 and sister Anne in 1960. Mum was a very engaging person and enjoyed lifelong friendships with other Japanese war brides and New Zealand women. They became her family, especially in the early years during a very difficult marriage. My parents separated when I was 10.

As children, our mother often reminded us that being biracial could be disadvantageous, so it was necessary to be well-educated. She tried to teach us Japanese as youngsters, but we lost interest when we started school. She made sure we were well-read. She had a plethora of Japanese books about history, politics, and medicine. I used to study the diagrams and images in her medical books, and eventually followed in her footsteps and entered nursing. Mum didn’t return to nursing as she felt her English was inadequate. Instead, she supported our family by sewing – she had her own business at home, and also worked as a factory seamstress alongside her Japanese friends. She was a hard worker and passed her work ethic onto us.

As a young child, I was proud of my Japanese heritage. At primary school in Auckland I often gave talks about Japan and brought in traditional Japanese items for “show and tell.” I also performed Japanese dances in my mother’s kimono at school and nursing homes.

We had many get-togethers with my mother’s war-bride friends and their families. There was a comfortableness about being together – Eurasian children were not common in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s.

As a teenager, I began to wrestle with being part-Japanese. It was only after I left New Zealand in the late ’70s and married an Australian that I began to accept my multiracial heritage. Most people I encountered in Australia were fascinated by and accepting of my cultural background.

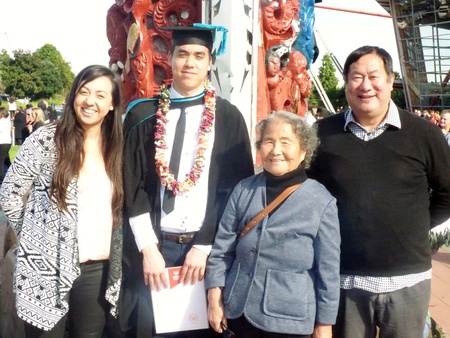

It was heartbreaking for the entire family when Mum passed away suddenly in August this year after suffering a stroke at the age of 91. She had been the center of our family. The clan always met at her home in Pakuranga in Auckland; she welcomed everyone.

I was unable to travel to New Zealand for the funeral because of the Covid-19 pandemic, so had to watch proceedings via the internet. I had so many more questions I wanted to ask her about her life.

Although my mother often wrote to her family in Japan (especially her sisters), she never returned in person – the timing was never right. It is our family’s biggest regret. But we plan to visit soon.

My son Leon grew close to his nana after finishing high school. He often sat with her and showed her pictures on his computer of her original home in Matsue City, which is still owned by her family, and many other places she knew in Japan. She loved those times, always commenting how some things change and others stay the same.

The last time I saw her in New Zealand, she said, “If I die tomorrow, I’ll know I had a good life and a happy life.” She experienced so much adversity throughout her life, yet she overcame it all. She was happy and contented.

* * * * *

LEON (Sansei):

Growing up, Nana and I lived a sea apart. She was in New Zealand and I was in Australia, so I only saw her a few times throughout my childhood. But after I finished high school, I moved to Auckland and lived with her while studying at the University of Auckland.

She was ageless in her personality and how she treated me. In her eyes, I was still a child who needed protection. She was a flow of repetitive advice, which I mostly didn’t mind. But sometimes it was too much: even though I was at university, I had a curfew and had to be home by 6pm for dinner!

For her, studying was the most important thing. She constantly encouraged me to work hard and not give up on my studies in order to get a good job. It was very much the Japanese in her trying to motivate me to reach the top. I always felt the pressure to finish. The day I completed my degree, she was very proud – even prouder than I was.

When I visited her as a child, I fell in love with her sushi, especially her inari. I couldn’t get enough. It was through food that we connected, because I was adventurous like she was.

She cooked a lot of soy and ginger-based stews. She said she wasn’t much of a cook but I enjoyed them – they were simple yet tasty. She especially loved seafood and was happy I ate it. She thought there was something wrong with anyone who wouldn’t eat fish. Her son (my Uncle Arthur) was the number-one target of her disappointment. “Not a true fish eater. Something wrong with him. Why he not like fish?”

After I moved out of her place I often brought her different foods, which she appreciated – especially the seafood. She ate a lot for an old lady, far more than my Australian grandmother. She could out-eat most people. It was always clear if she liked something, because if she didn’t, she’d let you know. She was blunt like that.

For the most part, I liked her bluntness. She wasn’t wishy-washy. Sometimes she unintentionally destroyed family members with her words. She never did it out of malice. She always tried to get the best out of her family. Blood was important to her, and she was wary of anyone outside the family. Her children and grandchildren knew they always had a place at her house.

Nana helped me embrace my Japanese side. Growing up in Australia, I didn’t have much Japanese culture in my life. In primary school, I was proud of my Asian heritage and had a lot of Asian friends. But my world changed dramatically when I went to high school in a less diverse, more European area. For six years, I felt I had to hide who I was. Anti-Asian sentiment and the bullying I experienced made me wish I was never Japanese.

Moving to New Zealand and living with Nana healed me, in a way. As I listened to her stories about the past and the traditions of her people, I began to appreciate who I was and where I came from. I discovered how similar we were. Even though we hadn’t spent much time together, we shared a lot of traits. My quiet nature and deep thinking reminded her of her father but I saw that in her also. She compared my artistic nature to many members of her family but she herself was a very artistically creative person. Though what stood out most when I first moved into her home was our shared germaphobia!

Nana was a strong woman who witnessed horror in Hiroshima, left behind her entire family and culture, but never let it defeat her. Her mind was sharp until the day she had a stroke in June 2020. That was the day she left us. I miss her stubborn opinions, alternative wisdom and the multitude ways she showed her love through kindness and generosity.

She wasn’t into technology but loved to sit with me and explore Japan through Google Maps, showing me where she’d grown up and telling me stories of the different places she’d been. It romanticized Japan for me. I wish I could have taken her back. I plan to go there one day, hopefully soon.

© 2021 June Baldwin and Leon Baldwin