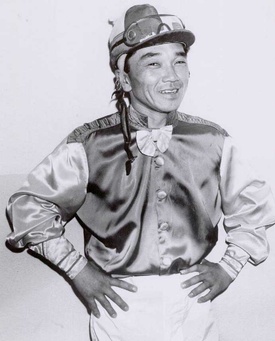

Strength is not just a tool for winning, it is necessary for survival. Jockey Johnny Longden was once rammed in midrace, knocked from his stirrups and sent flying downward in front of a pack of horses. He was saved by a jockey riding alongside him, George Taniguchi, who was so powerful that he was able to catch Longden with one hand…and righted him in the saddle, also with one hand. Incredibly, Longden won the race. The Daily Racing Form called it “the ultimate impossibility.”

From Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit: An American Legend (2001)

Not long after Laura Hillenbrand’s book became a New York Times bestseller, a friend brought it to George’s attention, “Hey, did you know you’re in Seabiscuit?” “How could that be?” George wondered, “I was just a kid.”

In fact, during Seabiscuit’s Cinderella-like career between 1935 and 1940, George Taniguchi was attending Mount Signal Grammar School, a country school near the Mexican border in California’s Imperial Valley. He flunked his first year because he could not speak enough English; Japanese was his first language. On his first day of school, the teacher asked him his name and when he responded Riyoichi, she said, “Oh, that will never do, I can’t pronounce that.” She arbitrarily chose the name George for him and it stuck.

By the time he reached the eighth grade, he was president of the graduating class. During the commencement ceremony in 1941, George delivered a speech titled “Marching Youth.” “I still remember,” George said sixty-five years later, the gist of it was “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” His teacher then, Charles Montague, wrote in his final report card, “He is a natural leader.”

Little did the Imperial Valley boy know at the time that he was destined to stardom in the Sport of Kings. And as a professional jockey from 1954 to 1968, and race track official from 1968 to 1990, he would come to know Seabiscuit’s old stomping grounds, such as Santa Anita and Bay Meadows, like the back of his own hand.

George’s father, Yoshito, was an Issei from Hiroshima. His mother, Kinuko, was born in Hawaii but reared in Japan. In 1924, shortly before the United States prohibited further Japanese immigration, Yoshito and Kinuko Taniguchi left Hiroshima, sailed across the Pacific, and made their way to the Imperial Valley. George was born in El Centro two years later.

When George was growing up, his father held a coveted position as a salaried employee of a large produce company, and his sole responsibility was growing four hundred acres of cantaloupes in an area west of Calexcio called the Mount Signal district. Issei farmers like Yoshito Taniguchi grew melons under hot-caps and brush-cover, two farming innovations that they introduced to American agriculture. Hot-caps and brush-cover were devised to accelerate plant growth. The key to success in the produce industry was to “come out early” and “get ahead,” the same principles that would later benefit George in his racing career.

George’s decision to become a jockey was the result of an amazing twist of fate. After World War II, the Taniguchi family resettled in Los Angeles where George’s father did gardening work. As a youngster, George never passed up a chance to do a skit or be in a play. “I always wanted to be an actor,” he admitted. For about two years he took acting classes at night at Ben Bard’s Players in Hollywood, the same drama school that claimed Alan Ladd among its alumni. George was always self-conscious about his height and worried that his small stature would limit the acting roles offered to him. But what George hoped would be his big break came in 1950 when MGM was making Go for Broke, a war picture about the famed all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team starring Van Johnson.

George auditioned for one of the lead roles, that of Tommy, a comical Hawaiian Nisei character. He rehearsed lines of Pidgin English until he mastered phrases like “you stay come,” “you go stay go,” and “I plenty okay now.” The director, Robert Pirosh, took a liking to George, but producer Dore Schary was adamant that the role had to go to a person actually from Hawaii.

Bound and determined to get the part, George demanded to see Schary, “Where is he?” Pirosh divulged that the producer was at Hollywood Park so George darted off to Inglewood. It was the first time he had ever been to a race track. He paid the entrance fee, but his hopes were dashed when he was flatly refused admittance to the posh Turf Club where Schary was enjoying the races. The doorman’s sneer spoke volumes. He might as well have said, “The likes of you will never be allowed in a place like this.”

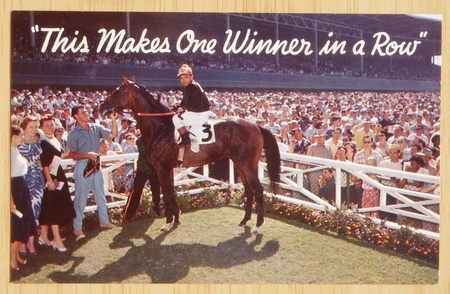

With his head hanging low, George meandered about the race track until he found himself at the winner’s circle. The spectators were going wild. Horse races drew larger crowds in those days much more than today, explained George, “forty to fifty thousand people screaming and clapping.” The cheers and thunderous applause aimed at the jockeys were intoxicating. Pointing to the riders, George asked a bystander, “Do they get paid for that?” “Not only do they get paid, they make a fortune!” replied the bystander. “And they were the same size as me! So right there I flipped my ambition and forgot about everything else except horses,” George declared. “I was determined to be a jockey.” It was a tall order for someone who up to that point had not once sat on a horse.

Before starting his training as a jockey, George did get a bit part in Go for Broke. It was only about three lines. When George talked about his distinguished career as a jockey, he talked about his wins the same way he talked about his slumps – matter-of-factly, devoid of the slightest hint of bravado. He revealed an immodest tone only once, when he passionately described his death scene in Go for Broke. “I did a good job,” he boasted. His character was shot during the climactic battle to save the Lost Texas Battalion and George demonstrated how he melodramatically threw up his arms and fell over. The scene took five takes. On the fifth take George decided to fling his head back and his army helmet unexpectedly flew off his head as he fell. The director liked what he saw and called it a wrap.

George credits Ben Yasuda, a fellow Imperial Valley native, for making it possible for him to launch a career in horse racing. Before the Second World War the Yasuda family farmed in Holtville and George knew of them through activities at the El Centro Buddhist Church, but he did not become well acquainted with Ben until they were incarcerated in the Poston concentration camp near Parker, Arizona.

After the war George worked for Ben as a clerk in a produce market in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles. It was during that time that Ben introduced George to an accomplished quarter horse trainer in Bakersfield named Jimmy Monji. Ben arranged it so that George could work forty-eight hours straight at the market in order to earn a full week’s wages, then George would sleepily drive the one hundred plus miles to Bakersfield and for the balance of the week he learned horsemanship from Monji.

George started out on an old, buckskin mare that he rode bareback. Maybe it was because he could not afford a saddle, but George convinced himself that he rode bareback to develop the incredible balance required in horse racing. He ran the stock horse over the soft sand of a dried-up riverbed so that when he fell off, which he often did in the beginning, he would not get hurt. Under Monji’s tutelage, George discovered how to ride with a horse rather than on a horse. George also mucked out the stables, helped break yearlings, and did other work in return for room and board during the days of the week that he was in Bakersfield. Then he would drive back to his clerking job in Los Angeles for another forty-eight-hour shift. George kept up the grueling schedule for a year and a half. Thinking about it in retrospect, he said, “That was rough.”

Once George felt confident in his riding ability he bid farewell to Monji and quit the produce market altogether in favor of a job at Northridge Farms in the San Fernando Valley. He slept on a cot in the barn and walked the racehorses after their workouts to cool them down. His job was called “walking the hots.” He also had endless barn chores to do, but occasionally he was given the opportunity to work the racehorses on the training track. It was at Northridge Farms that George mounted a thoroughbred for the first time.

Beginning in 1952 George worked as a freelance exercise boy at Hollywood Park, earning $5 per horse. According to one observer, it was due to his “sheer unrelenting perseverance” that George’s name began to circulate around the stables. His strong work ethic caught the eye of Larry Kidd, a veteran owner and trainer of racehorses and nationally renowned instructor to jockeys. George signed a contract with Kidd the day after they met in July 1953. Kidd was quoted in The Daily Racing Form (April 25, 1955) as saying that George was “the best rider I ever had. He was a paragon of punctuality and dependability. He was a hard worker, and never flinched from mud, rain or cold.” George’s regard for his mentor was equally high, “He’s the most wonderful man in the world. He’s taught me more than any ten men put together. He taught me everything I know about race riding.”

* The original version of this article first appeared in Imperial Valley Pioneer (August 2006), the newsletter of the Imperial County Historical Society.

© 2020 Tim Asamen