Connected to Japanese Society and Culture

Many Shin-Nisei (children of post war Japanese immigrants) on the U.S. continent do not identify with being Japanese American because to them it suggests a history of incarceration and cultural distance from Japan. For those whose parents came from Japan after World War II, their family history of the war was from the Japan side, not the U.S. side. Rather than experiencing incarceration, close relatives may have experienced the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the Battle of Okinawa, or other bombings in the Japanese archipelago.

Tracy grew up in California with a mother from Japan. She reflected, “I feel like the Japanese American community bonds solely over internment. It would be nice to find something contemporary.” At the same time, she recognizes the importance of teaching incarceration history because she says that “things happening today show that we haven’t learned from it,” alluding to the racist and xenophobic treatment of Muslim Americans. So Tracy is not saying that incarceration history is unimportant. Rather, she wonders if there is a more contemporary experience and identity that can bring Nikkei Americans together.

(photo by Clem Albers/Department of the Interior War Relocation Authority, National Archives). Photo Courtesy: NJAHS

Sara was raised in the Midwest, and also has a mother from Japan. In her mind, “Japanese American” refers to being born and raised in the United States, and not growing up with contemporary Japanese language or culture. She explained that “they seem to have a superficial sense of being Japanese” because “they talk about Japan like it’s a class of something; it’s not a lived experience for them.” This contrasts with her knowledge of Japanese culture and language and her experiences visiting Japan with her family. Sara has been the recipient of a Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL) Scholarship and has attended their events, but feels distant from them and the Japanese American community.

Mixed Heritage

Naomi, whose mother is from Japan and father is a white American, explains that, “I usually think of Japanese American as someone of 100% Japanese descent, so I never really identified that way.” Since she associated Japanese American with people who are not of mixed heritage, she did not think it included her.

Martin, whose mother is a white American and whose father is from Japan, said he does not like associating with the term “Japanese American” for several reasons. First, he doesn’t like racial terms and doesn’t want to be categorized in a racial or ethnic way. Second, when attending an international high school in Tokyo, other “half American and half Japanese” never referred themselves as Japanese American. Third, by college he already had a nationality-based identity. So although he is a U.S. citizen of Japanese ancestry, Martin identifies not as Japanese American but, rather, as Japanese and American. He is more focused on his two national parentages than on his racial or ethnic backgrounds. Instead of seeing himself in racial or ethnic terms as white and Japanese/Asian, he sees himself in national terms as half American and half Japanese. His upbringing outside of the United States encouraged him to see himself in this way.

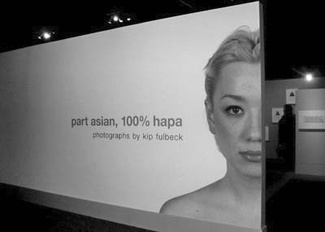

Many mixed-race Nikkei Americans whom I interviewed feel excluded from identifying as Japanese American based on phenotype (physical characteristics) and other racial connotations. “Japanese Americans” is an ethnic term that is usually seen as part of the pan-ethnic grouping Asian. But Asian is a racial category that implies phenotypical differences from whites and blacks, such as eye shape and skin, hair and eye color. What, then, does it mean if Nikkei Americans don’t look Asian?

Addressing Diversity

Even though my interviewees may not be representative of the larger Nikkei population in the United States, their perspectives do illuminate some aspects of how people currently understand being Japanese American.

For one, they reveal how central the incarceration and prewar immigration experience in the United States is to current constructions of the Japanese American community. There are numerous legitimate reasons for this. But when we include more about modern Japanese and Hawai‘i history in Japanese historical narratives, (without undermining the importance of incarceration or prewar history), a wider population might be better able to relate. Some Japanese American history books include the experiences of postwar migrants from Japan and people in Hawai‘i contextualizing incarceration in a larger history of ethnic Japanese experiences that transcend the U.S. continent during those particular years.

I think it is most useful when these pre-and postwar histories are recognized as distinct yet overlapping, rather than as somehow woven together. When woven together as a single narrative, it is common to see discussions of Hawai‘i plantations, then incarceration, then postwar Nikkei political successes in Hawai‘i. Instead of this, subgroups within the Nikkei American population could be identified and each of their histories recognized separately, intersecting as people migrate from one place to another. The audience could develop a better sense of how Nikkei experiences have differed yet overlapped as people have migrated between Japan, Hawai‘i, and the U.S. continent, among other places.

There is also rich material to explore by comparing how different groups of Nikkei Americans have experienced certain events or time periods. When we look comparatively at something like the incarceration (and non-incarceration) of Nikkei in Hawai‘i and on the U.S. continent, we get a deeper understanding of both communities. When immigration history looks comparatively at Japanese migration to the United States in both the prewar and postwar periods, we gain new insights into how both nations, and Nikkei American experiences, have changed over the decades. How different is a Japanese American identity centered around speaking Japanese and visiting Japan regularly and one centered in Japantowns, basketball leagues, and U.S.-based Japanese American culture?

Over the past 15 years, we can see many community organizations becoming more inclusive. For example, organizations like the Japanese American National Museum and NJAHS have held exhibits focusing on the experiences of mixed-race Japanese Americans. Organizations such as Kizuna in Los Angeles have expressed as a goal the development of “strategies for integration 1st and 2nd generation Japanese American youth and families.” Whether broadening the focus of Japanese American organizations or renaming groups “Nikkei” instead of Japanese American,” a larger goal that we are all working towards is including and meeting the needs of the changing population of people of Japanese ancestry in the United States.

The marginalized Nikkei experiences mentioned in this essay are just a few examples. An ongoing task for us all is to continue to identify and address the needs of underrepresented groups in the community. As we continually reconstruct what it means to be Japanese American or Nikkei, who does this include? As being of mixed-race, Japanese and Caucasian, becomes increasingly mainstream, how do we include other mixed-race Nikkei? What other people of Japanese ancestry in the United States might not identify with mainstream narratives of Japanese American history and identity and what can we do about this?

As our community continues to evolve proactively asking these questions can help us find new answers to what it means to be Japanese American.

*This article was originally published in Nikkei Heritage (Fall 2015: Winter 2016, Vol 26, No. 1).

© 2016 National Japanese American Historical Society