“We (Tule Lake internees) never had a crisis of loyalty…we had a crisis of faith in our government.”

—Dr. Satsuki Ina, speaking at a plenary session of

the 2012 Tule Lake, California, Pilgrimage

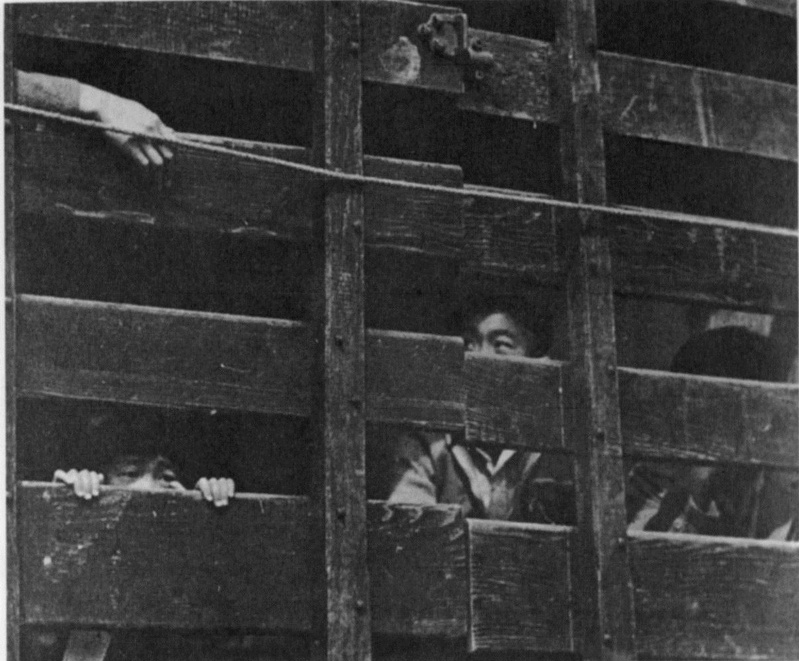

On this day, February 19th, 72 years ago, Executive Order 9066 was passed, marking the beginning of the wholesale imprisonment of the United States’ entire west coast population of more than 110,000 Japanese American men, women, and children.

NYC documentary filmmaker, Konrad Aderer, 46, is on a mission to tell one of the most compelling yet still unknown stories about what really happened to our families during the internment years of World War Two at Tule Lake Concentration Camp.

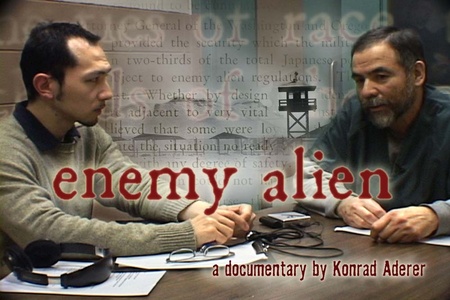

I first learned about Konrad Aderer around the time his documentary, Enemy Alien came out in 2010. In that film, Aderer parallels his own family’s internment at the Topaz, Utah camp for three and a half years with the post-9/11 arrests of Muslim immigrants. His documentary chronicles his efforts as he joined the struggle to free Farouk Abdel-Muhti, a Palestinian activist.

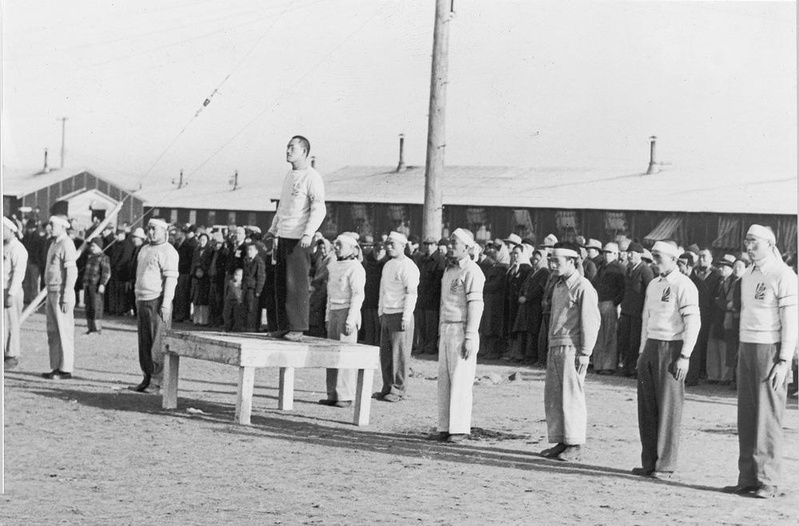

Tule Lake Concentration Camp, located in Newell, California, was perhaps the most infamous of the American internment camps. It was an important place in the unfolding drama of the “No-No Boys” who refused to answer the U.S. government’s skewed “loyalty survey” as well as with the “renunciants” who gave up their US citizenship and went to Japan. It was in Tule Lake, as in John Okada’s magnificent 1957 novel, No-No Boy, where some families were torn apart with one son joining the US army while the other declared himself a “No-No Boy”. Doing so meant risking being branded a traitor by defying the government’s heinous pogrom.

In retrospect, of course, the “No-Nos” (there were women too) were perhaps the truest Americans as they were willing to face ostracism of their community, testing the integrity of the core values of democracy, freedom, and equality that America was purportedly fighting to defend in World War Two. For them, signing “no-no” was the only morally correct choice.

(In Canada, it is important to remember too that even before Japan and Canada were at war, that on January 7, 1941, a Special Committee of the Cabinet War Committee recommended that JCs not be allowed to volunteer for the armed service on the grounds that public opinion was strongly against them. As if anticipating a war against Japan, between March and August 1941, JCs over the age of 16 had to register with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Following Canada’s official declaration of war on Japan, the War Measures Act, Order in Council P.C. 9591 required that all Japanese Nationals and those naturalized Canadians after 1922 to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens. On December 16th, P.C. 9760 was passed requiring mandatory registration of all persons of Japanese origin, regardless of citizenship, with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens. Mass incarceration and confiscation of personal property was soon to follow.)

Finally, it is at our peril that we ever allow these stories and memories, especially the most painful ones, to be lost from our community’s collective consciousness. Our history needs to be taught with unrelenting vigour and passion to our children lest they ever forget the ultimate price that their Japanese ancestors paid to live here in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

* * * *

Can you take us right back to the beginning? What was it about the Tule Lake Internment camp that interested you?

Like many people, I was reawakened to the topic of the wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans in the wake of 9/11. I started directing my first feature documentary, Enemy Alien (enemyalien.org) which interwove my grandparents’ incarceration with the fight to free a post-9/11 detainee. This documentary required a fresh look at the “internment” (and was hard to get support for) because this detainee wasn’t a nice cab driver or someone living the accepted immigrant dream of Americanization, but a Palestinian political activist who organized hunger strikes and other resistance among his fellow immigrants in detention. It was in finding a parallel to his experience in the American concentration camps of World War Two that I rediscovered the story of Tule Lake and how it was suppressed so many years.

How did the project evolve from that point on?

When I finished Enemy Alien and started screening it, it was important to me to take it to the Tule Lake Pilgrimage. Partly this was because I had included a section on Tule Lake in the film and wanted to see if the way I interwove it with this story of post-9/11 detention was accepted by the incarceree community. Also, I wanted to connect with camp survivors who resisted incarceration because I felt an affinity for that choice. I was very nervous about how people who had lived through Tule Lake would react to my film, but I got an overwhelmingly supportive response. And as I went through the pilgrimage experience, which itself was life-changing, I started developing my project on Tule Lake. I went to three more pilgrimages up to the most recent one this past summer, getting to know people’s stories and shooting footage.

When did it become a project that you knew you wanted to make a documentary of? Was there a sense of personal mission? What were the truths about TL that struck you?

I really had it in my mind to make a documentary on Tule Lake back when I was researching it for Enemy Alien. I was so drawn to the story I immersed myself into a lot more material than would fit into Enemy Alien, and so I had this leftover hunger to really tell the story. I also saw that no documentary had been done before on Tule Lake exclusively even as the generation of incarcerees were in their 80s and 90s. So there was a sense of responsibility in that I was the only one I knew of who was going to make a documentary on Tule Lake while people who lived it were still around. But I also had a particular sense of how the story was more resonant than ever after 9/11 and all that society has wrestled with since. In this story you have the devastation inflicted on an immigrant community by a flawed ideal of “loyalty” that still haunts our right-left discourse and inflicts untold suffering on immigrant communities.

Why is this episode in American history an important one to remember? Why isn’t it better known?

Because of the terrifying nature of being a member of an “enemy alien” nationality in time of war, it’s taken more than 70 years for the Japanese American community itself to come to terms with people who didn’t fully cooperate with the World War Two incarceration program. Even in my generation growing up in the ’70s, if you heard about “internment” it was seen as so terrible because it was done to U.S. citizens. Which implies that it’s okay to lock up people wholesale if they’re noncitizens. The next oft-repeated mantra about the “loyalty” of Japanese Americans is that even as incarcerated people, they signed up for the U.S. armed forces, and the 442nd regiment was the most heroic regiment, et cetera. Not to take anything away from the bravery and integrity of those who enlisted, but the right of people not to be mass incarcerated has nothing to do with their willingness to kill and be killed for their country.

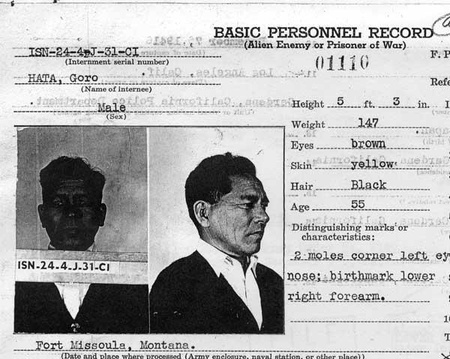

With “Islamic terrorism” and “illegal immigration” still at the forefront of our Western consciousness and dominating our military and enforcement priorities, Tule Lake is more relevant than ever. No, the U.S. government isn’t incarcerating 110,000 people of a particular race, but federal and local enforcement still embraces racial profiling. We’ve been locking up about 400,000 people a year as immigrant detainees, and these two policies are intertwined. Also, you don’t have to forcibly remove and incarcerate people to effectively imprison them. Today people live among us who are living in the completely different world of being out-of-status. The process and the threat of deportation played a huge role in the Tule Lake saga just as today. Exclusion, the fact that the Issei—the first generation, the parents of the people who speak out in this film—were flat-out barred from becoming U.S. citizens, underlies every aspect of Tule Lake.

Tule Lake Segregation Center was an overcrowded, ultra-pressurized purgatory where many of the racially polarized, militarized conflicts we wrestle with now were represented. Guantanamo, Ferguson, Oakland—and in New York City where I live, people of certain ethnic groups and the people who protest and resist racially biased enforcement are still being demonized and surveilled.

How do you want young Americans/Canadians to connect to this story? Why is it important for them to remember?

Can you share one or two of the personal stories that you have learned about life at Tule Lake? What made the “segregation center” different from the other concentration camps? What kind of intimidation, threats, and torture was used there?

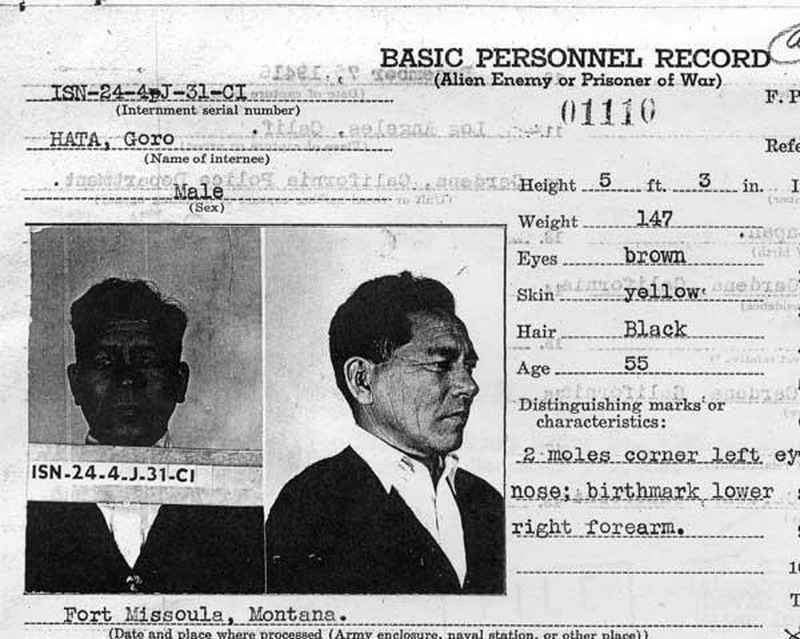

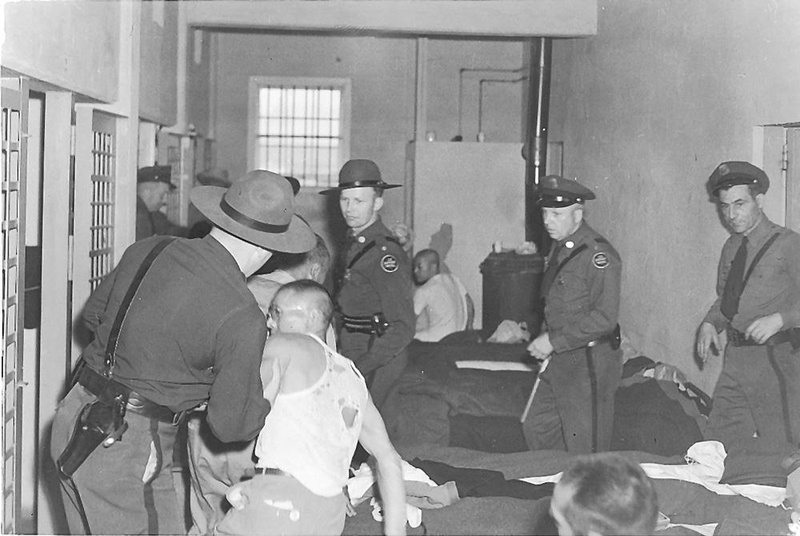

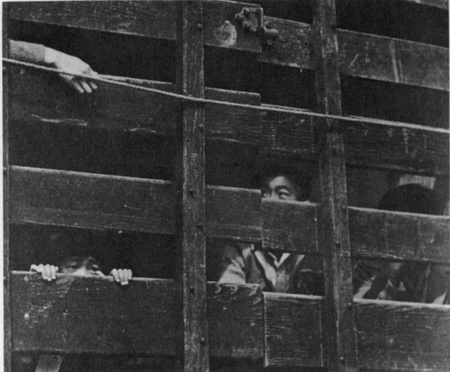

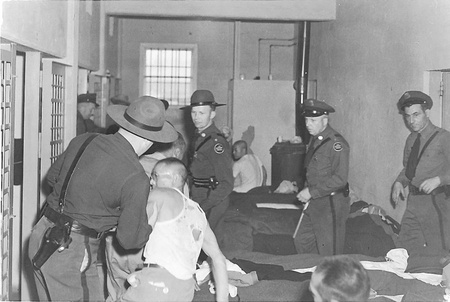

While making public statements about “relocating” Japanese Americans in a respectful way “as a democracy should,” the War Relocation Authority turned Tule Lake into a prison environment to punish people for their so-called “disloyalty.” The authorities, armed MPs, and Army personnel had no qualms about using threats and brutality on detainees who posed no physical threat to them.

Bill Nishimura has a wry way of recounting the transparent manipulation the camp administration tried to pull on him. The FBI took his father away to a Department of Justice camp soon after the war started. Then, when Nishimura refused to answer the “loyalty questionnaire,” they released his father and let the family reunite in Poston, the concentration camp they were in. Then, a smiling administration official asked Nishimura, “so how do you like having your father back.” He replied that it was wonderful and he was very grateful. Then they asked him, “so what do you think of questions 27 and 28?” When he still refused to answer, they put him on a truck to Tule Lake.

There was just a casual brutality in these incarcerees’ lives that hasn’t been retold before in the context of the camps, which have previously been conveyed as unjust but peaceful. Once the government had produced “disloyal” Japanese, the gloves were off. Morgan Yamanaka was rousted one night and locked in the camp stockade. He was interrogated and had a nervous young soldier push a rifle right against his stomach. Another subject of the documentary, Junichi Yamamoto, was witness to the execution of a detainee in broad daylight. The fact that the people in this documentary stuck to their principles in the face of all this is amazing.

© 2015 Norm Ibuki