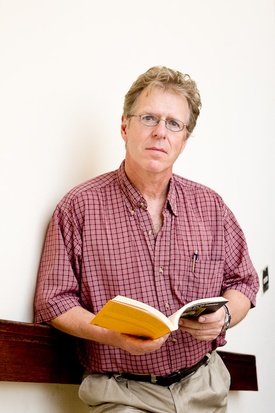

Composer musician, scholar of Latin American literature, trombonist and dekasegi researcher, Marco Katz could be defined by any of these titles but there is one that suits him best: admirer of the poet José Watanabe, the main reason for his recent visit to Peru.

Marco and Betsy, his wife, arrived from Canada with the poetic and academic pretext of getting to know the land of the Nikkei poet born in Laredo, Trujillo, where this North American couple moved, visiting bookstores in Lima, chatting with experts on Japanese immigration in Peru and left (after passing through Machu Picchu) full of satisfaction.

“In Laredo I found the José Watanabe Varas library, about which nothing is said on the Internet. There I met professor Félix Gutiérrez and librarian Roel Luis García. They showed me their books and took me to the poet's family's house,” says Marco, who carries under his arm the children's stories of the author of The Winged Stone and the book he is reading at the moment: El ombligo en el adobe. Sieges of José Watanabe, the biography written by Maribel de Paz.

From music to literature

Marco was a musician in New York, a member of salsa groups, when he met the great Charlie Palmieri and Mon Rivera, with whom he played in Puerto Rican bands with which he began to hear, live, his first words in Spanish. The lyrics of the songs were the next stimulus. “Hey how it goes, my rhythm, good to enjoy”, had to mean something.

Thus, at the age of 48, Marco decided to study literature (or philology, as they call it in Spain), at the Complutense University of Madrid. His rudimentary Spanish could not have had a better place to get rich. There he read Cervantes, García Márquez, Carpentier, Vargas Llosa and other great surnames that inclined him towards the continent of the wonderful real.

“When I did my master's degree, a professor began to talk to us about the literature produced by the Japanese imprisoned in the United States during World War II. It was a story that many did not know and that is how I began to be interested in writers of Japanese origin in Latin America.”

Nikkei literature

Names like Alejandro Sakuda, Amelia Morimoto and Augusto Higa Oshiro began to occupy his mental library; the one where the surname Watanabe had been engraved on the winged stone of his literary hobby. In Canada, where he currently lives, Marco Katz chose Nikkei writers from the United States, Canada and Peru for his master's project at Humboldt State University.

“Sorry for staining these sacred lands with my blood” was the title he chose for that document that would not be the last investigation into writers of Japanese origin. From Cusco to California: José Watanabe and Naomi Quiñones in the Nikkei Diaspora, which he published as part of a conference at the University of California, was another of the titles with which Katz began to become a reference for these topics.

In 2007 he presented his research Whose Diaspora Is It Anyway?: Japanese, Peruvians and Dekasegi. Citizen Narrative, for the University of Alberta, in Edmonton, Canada, where he continues studying, playing the trombone and marveling at the writings of Joy Kogawa, the Canadian poet who survived World War II, and José Watanabe.

Chasing the poet

“I fell in love with Watanabe's texts. I really liked his way of using language, his ideas, images and concepts. This winged stone that flies but does not fly. Or in Praise of Restraint, where he explains the idea of achieving the warmest passions through restraint.”

“I fell in love with Watanabe's texts. I really liked his way of using language, his ideas, images and concepts. This winged stone that flies but does not fly. Or in Praise of Restraint, where he explains the idea of achieving the warmest passions through restraint.”

In a part of the poem “The Hands” Watanabe writes: “My father came from so far away, he crossed the seas, he walked and invented paths, until he ended up leaving me only these hands and burying his like two very tender fruits already extinguished.” And in “The Riddle” he notes: “The parsley announced my father, Don Harumi, waiting for his frugal soup. Thank you from this country: a Japanese who did not forgive the absence of that local cooking secret on the table!”

“I liked Watanabe also because of the issues of identity. I am American but my father was Jewish and my mother was from a fundamentalist Christian family. She was born in Nigeria, where her parents were missionaries. So who am I? I see a lot of that in Watanabe, who said he was Peruvian, but that he had to work hard to be one. The same thing happens to me in Latin America.”

Identity in the diaspora

Marco and Betsy were in Laredo, searching the streets for the roots of the Nikkei poet to find out who Watanabe is. “In Lima I went to the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru, where I saw the spindle, which is used to spin textile fibers, and I thought about Watanabe's The Huso de la Palabra, and the relationship with his mother and the cultures Moche and Chimú. Who are the Watanabe Varas children? “Those are some things I want to explore.”

Watanabe's identity was a way to continue his studies on dekasegi, which allowed him to investigate the cases of the writer Augusto Higa and the singer Alberto Shiroma, who is a global phenomenon with songs translated into several languages.

“I have discussed a lot at conferences about the diaspora, which is a return that is not a return. At one point the Japanese government decided that it did not want Nikkei and paid them to return to their countries. In the United States they paid them ten thousand dollars to sign a document in which they swore that they would not return to Japan for ten years,” says Marco Katz.

That is why it is so complex to talk about identity. For now, Marco Katz prefers to enjoy Watanabe's poetry in Chile, where this philologist, jazz performer, composer of music for television and author of an album with songs based on the collection of poems The Stones of Heaven, by Pablo Neruda, which will be released This year, he will live with Betsy for a while, while she studies the celebrations for the centenary of Latin American independence and he explores the last remnants of the Laredo poet's work.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 66, April 2012 and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2012 Asociación Peruano Japonesa; © 2012 Fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa / Fernando Yeogusuku