Like turkey on Thanksgiving for Americans, a “must have” for Japanese and Nikkei around the world on New Year’s Day is a nice, warm bowl of ozoni, also known as “mochi soup.”

Bowl of ozoni (included mochi, mizuna, kombu, Japanese mushroom, and chicken in a shoyu-flavored chicken broth). Photo courtesy of Soji Kashiwagi.

But unlike Thanksgiving, where there’s no threat of bad luck or misfortune if you don’t eat turkey, ozoni on New Year’s is loaded with good luck symbolism.

Eat your New Year’s ozoni (so say the Japanese dating back centuries) and you will have good luck, longevity, and happiness for the rest of the year. Miss your ozoni and well…let’s just say that’s a risk most do not wish to take.

What started in Japan has been carried on by generations of Nikkei from California to South America to everywhere in between. If it’s January 1, we all know it’s time for ozoni.

And so there we were—all 24 of our family and friends gathered together at my parent’s house in Loomis, California on New Year’s Day 2011—with chopsticks in hand, mochi in the bowl, and delicious ozoni happily in our stomachs. Bring on the New Year!

Soji Kashiwagi's cousin, Teruko Nimura, enjoys her mochi on New Year's Day. Her niece, Celia, has a mouthful of mochi as well. Photo courtesy of Soji Kashiwagi.

But wait, I’ve skipped a step or three here. Ozoni recipes and ingredients vary depending on which region your ancestors came from in Japan. But the one common denominator that every bowl of ozoni must have is the sweet rice cake known as “mochi.”

And if you make your mochi the “old school” hand-pounded way, you know how much work goes into good luck, longevity, and happiness for the new year. It’s not only work, it’s a full day of back-breaking, heavy-lifting work-work. (That’s right…it’s double the trouble “work-work.”)

Of course, for those who aren’t into hard, manual, physical labor, you can buy your mochi at the local Japanese market or a “manju-ya.” In California, you can find fresh mochi for the New Year at manju stores in San Francisco, Sacramento, San Jose, and Los Angeles. All are made in huge quantities, and manufactured by industrial strength mochi-making machines.

And that’s fine if you like your mochi machine-made. But if you’re into old-fashioned tradition and culture, and enjoy eating the smoothest, tastiest mochi made with tons of “kimochi,” the only place to get your mochi is from a mochitsuki.

In Nikkei communities in California and across the country, the annual mochitsuki still takes place in Japanese American churches, Japantowns, and at the homes of Japanese American families.

In the old days, our Nisei elders will tell you, Japanese families would get together for mochitsuki just before New Year’s, spend the day pounding, shaping and socializing, and then would split 300 pounds of mochi three ways.

Ben Kobashigawa, Chizu Omori, Yuko Franklin, and Sadako Kashiwagi shaping mochi. Photo courtesy of Rita Takahashi.

But nowadays, with the advent of modern-day technology, many groups and families have done away with the labor intensive hand pounding, and have switched to the popular made-in-Japan mochi-making machines.

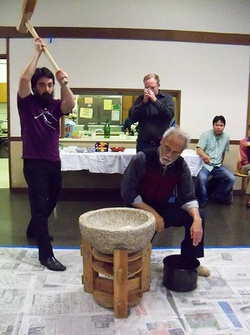

However, a handful of families and groups, like the one my parents have been involved with for over 30 years, still make it the old-fashioned way: Pounded with large wooden mallets (“kine”) in a large granite bowl (“usu”).

In my hometown of San Francisco, a group called the Center for Japanese American Studies used to hold its annual mochitsuki at a church in Japantown every year since 1969. However, since the Center dissolved several years ago, the mochitsuki is now sponsored by the Japanese American National Library. My parents have been involved for over 30 years, and when my schedule allows, I come up from Southern California to lend a helping hand.

In the early years, members of the Center and their families would gather annually to participate in the mochi pounding, shaping, and molding. But as time has passed, many original members have either moved on or died. So out of necessity, the event has evolved into more of a “community-wide” affair. Last month, a press release was sent out asking the public for help, especially with the pounding.

“Who’s coming this year?” I asked Karl Matsushita of the Japanese American National Library.

“I don’t know,” he told me. “It’s going to be whomever shows up.”

“Uh oh,” I thought. You mean there was no list of young, able-bodied pounders signed up and ready to go? What if no one shows up except me?; At 48, I’m not exactly young anymore. My dad can still pound, but he just turned 88. This all made me very uneasy.

Pounding mochi is far from being easy breezy. The kine is this large, wooden mallet with a heavily-weighted “business end” for optimum pounding power. At the beginning, it’s fun to pound down on the mochi with authority. But as the pounding continues, that kine becomes heavier and heavier, and pretty soon the arms and back begin to ache. What starts out as fun is now all about pain, and lots of it.

Ideally, it’s best to have a group of younger folks, with lots of muscles, who can rotate in and out, and pound all day long. At 11 a.m. on December 28th, I looked around the room and the only people there to help were my mom, and two guys, one older than me, and the other quite older than me.

“This is not good,” I thought to myself, as I stood in the kitchen, overseeing the steaming of the rice.

We arrived at the Christ United Presbyterian Church social hall at 9:30 a.m., and helped with setting up the tables, taping down the plastic on the tables for mochi shaping and molding, and adding more plastic and newspaper on the floor, which became the designated space for the usu and mochi pounding.

In the kitchen two days before, Karl had the Koda Farms “Sho-Chiku-Bai” mochigome (sweet rice generously donated every year by George Okamoto of Nomura & Co.) soaking in water in several large, plastic trays. On the stove, Karl also started steaming the first batch of rice, which is placed in four, custom-made wooden boxes, stacked one on top of the other over a large pot of boiling water.

We were going to make 75 pounds, a modest amount compared to some churches that make 800 to 900 pounds every year. But 75 pounds is quite enough, especially when you don’t know how much people power you’ll have from year to year.

Speaking of people power, at 11:30 a.m. I looked around the social hall and people were starting to arrive. And thank goodness, there were some that were younger than me. One even brought his own “pounding gloves.” The only thing left to do was to put these people to work!

However, the rice wasn’t quite done yet, and since Jim Hirabayashi, the Nisei who had steamed the rice for over 30 years, was unable to attend, it was up to a committee of about four people to decide whether or not the rice was ready to go.

“It’s still a little too hard,” said my mom. We waited 15 minutes and tasted it again.

“I think it’s ready now,” said Karl.

No one knew for sure since Jim was the only one who knew for sure, and he wasn’t there. (Note to those who wish to do this on your own: consult with the elders on the proper procedures before you attempt to do this on your own.)

“Let’s go,” I said. I lifted the three boxes from the top, and Karl picked up the bottom box and carried it over to the usu where he dumped the hot rice into the granite bowl.

Seeing the steaming rice, two younger-looking guys picked up the kine and began pushing the rice together in preparation for the pounding to follow.

Meanwhile, back in the kitchen, the empty box was returned and I filled it with three small pots of mochigome, carefully leaving a circular gap in the middle for the steam, and pushed the rice away from all four corners for more even cooking. The box then was placed on top of the stack. This process and the rotation of boxes was repeated all-day long until we were done with the last box.

Back on the floor, the pounding action had begun. One thing I noticed is that there’s no single way of pounding mochi. Everyone has their own unique style and approach. Some can pound so hard that you can hear the wood go through the mochi and make a popping sound into the granite. Those not as strong strike the mochi with a thud.

And then there’s everyone in between, taking their turn. Little kids, teens, moms and dads, anyone and everyone who wanted to give it a try gave it a try. My dad, Nisei writer Hiroshi Kashiwagi, at 88, took his turn a few times. So did Dick Kobashigawa, a bent-over Nisei man who walked in with a cane. At first, I thought he was strictly an observer. But then he put down his cane, picked up the kine and started pounding down on that mochi with all his might.

“How old is your dad?” I asked Ben Kobashigawa, who was watching with me from the kitchen.

“Ninety-six,” he said.

Amazing.

And that’s when it hit me: this event, this mochitsuki, was all about Japanese tradition and carrying on a tradition centuries in the making. Community elders like my dad and Dick Kobashigawa—without saying a word—got up and demonstrated how it’s done, and in the process, were literally passing it on to us.

Nisei seniors, Sansei, Yonsei, Hapa, Shin Issei, non-JAs—old and young—we were all there to keep the flame burning, bonded by this tradition and Nikkei community spirit. And like it was in the old days, we came together to work, to socialize and talk story about old times and new, and to participate and partake in the making and eating of New Year’s mochi.

Some wrapped it in nori, dipped it in a mixture of shoyu and sugar and popped it in their mouths. Some rolled it in kinako, a brown, soybean powder. And still others took their mochi, folded in a ball of sweet bean paste and enjoyed “an mochi.”

And before the day was done, everyone was served a bowl of homemade ozoni made special by our friend from Japan, Yuko Franklin. Filled with Chinese barbecue pork, Japanese mushrooms, and nappa, Yuko-san then added in our hand-pounded, hot-off-the-usu mochi into a pot of shoyu-flavored chicken broth.

And how did it taste? Like it was loaded with longevity, good luck, and happiness for the New Year.

Soji Kashiwagi enjoys the "fruit of his labor" on New Year's morning. Photo courtesy of Soji Kashiwagi.

© 2011 Soji Kashiwagi